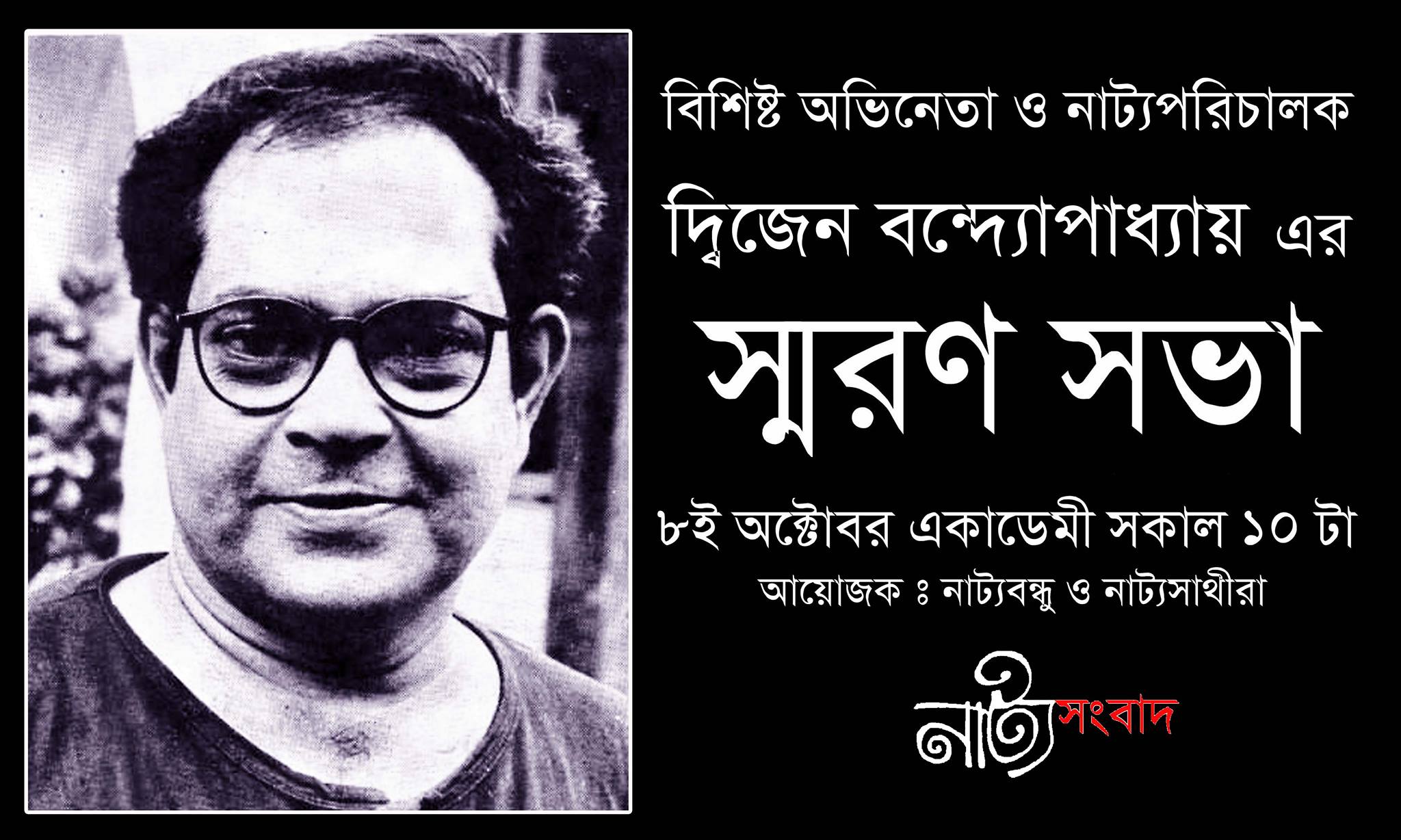

“Dwijen is someone I would like to call a ‘natya-chef’. He would prepare the recipe by judiciously slicing off a layer of our daily existence, and then, like a true pathologist, scrutinise it. He would dissect it, analyse it, add on the necessary flavours, and when the final dish would be prepared and served on stage, it would always be something unequalled.” This is how Bibhas Chakraborty, a veteran theatre personality, remembered Dwijen Bandyopahyay at a condolence meeting remembering Bandyopahdyay at the Academy of Fine Arts, on 8 October, 2017. The "abhineta adwitiyo" (an inimitable artist), as Chakraborty puts it, passed away on the 27 September, 2017. On the 8 October, several people from both the theatre and cinema world remembered how Bandyopadhyay’s theatrical visions influenced their lives.

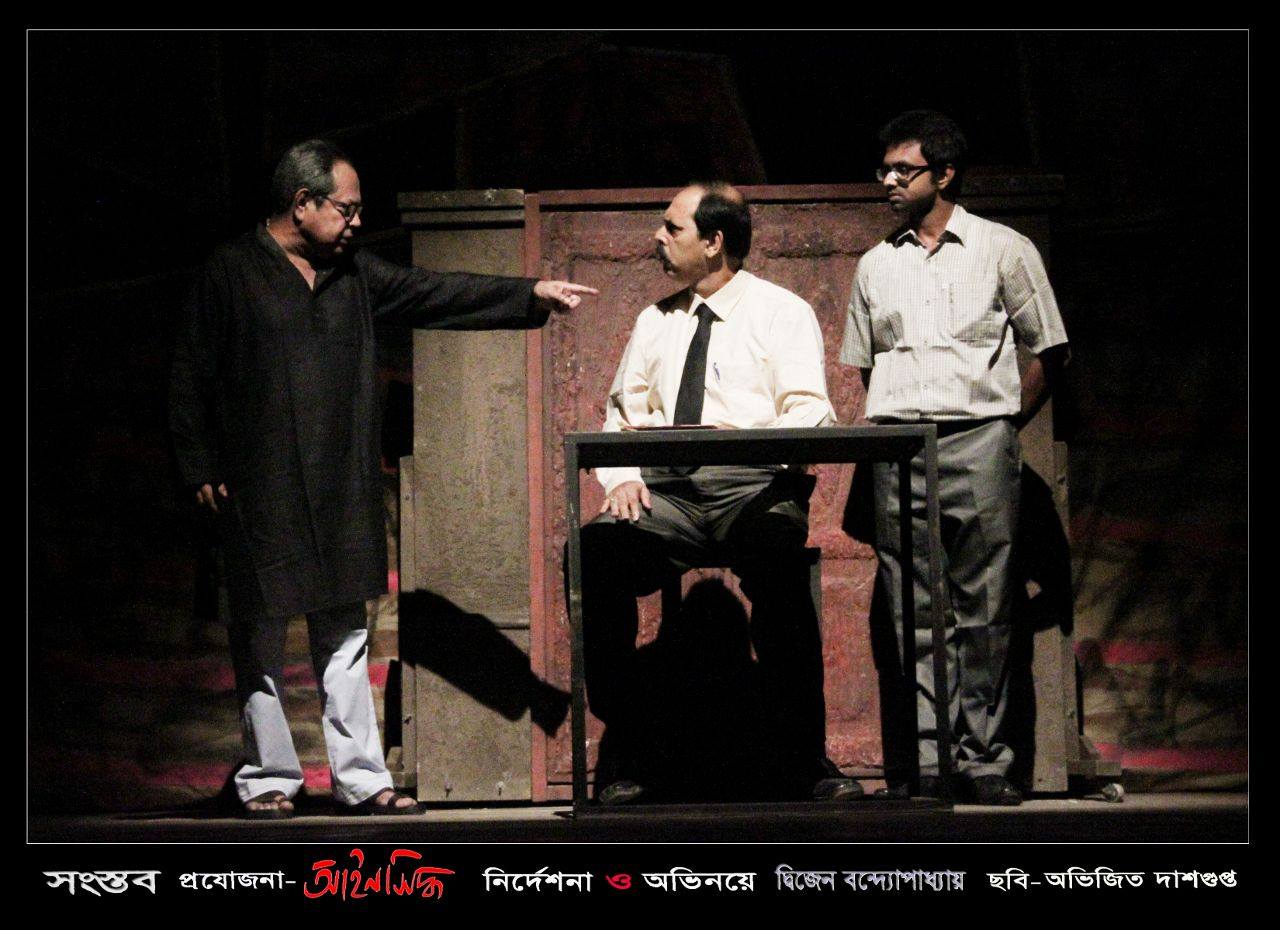

The actor, theatre director and lecturer, was born on 22 September, 1949. He became a consistent and loved presence in Bangla theatre from the seventies onwards. Bandopadhyay began his journey with Bagbandi (1972) directed by Subrata Nandi and gained acclaim in his earlier acting days with unforgettable performances in plays such as Amritakshar (1978), Samabartan (1980), and Mallabhumi (1987). Even stalwarts like Shambhu Mitra were equally convinced of Bandyopadhyay’s prowess as an actor and casted him in his plays such as Galileor Jibon and Dashachakra. Soon enough, Bandopadhyay went beyond being just an actor and became actively involved in directing and co-directing plays, rendering some of the milestones of Bangla theatre like Socrates-er-Jobanbondi (1988) and Dhunistambha (1990). He created his own theatre group, Samstab, in 1982. A substantial part of his productions were plays by the renowned playwright Mohit Chattopadhyay, who influenced Bandopadhyay’s ideology and artistic vision to a great deal. Plays like Mushthijog, Sundar and Nishad, the collective brainchildren of Mohit Chattopadhyay and Dwijen Bandyopadhyay, gained immense popularity and almost achieved a cult status in the history of Bangla theatre. Bandyopadhyay’s popularity however transgressed the precincts of theatre as he became an equally well appreciated actor in television and cinema. Known for his impeccable comic timing, he became a household favourite with him playing Panna in a popular Bangla sitcom Chuni Panna in the early 2000s. His oeuvre gradually expanded genres, as he worked in mainstream successful Bangla movies as well as relatively small indie productions.

One can elaborate on the incredible diversity and range of Dwijen Bandyopadhyay’s work, but his close ones gathered at Academy, chose to elaborate on his ideas, methodology and politics. Bibhas Chakraborty believes that there can hardly be another actor like Dwijen Bandyopadhyay. For him, there are many actors who have mastered the techniques of naturalistic acting in theatre but Bandyopadhyay’s performances are not something that can be summed up just in terms of their expertise in techniques. He delivered performances which, inspite of a layer of naturalism, also had sublime undertones of being very experimental. This sublime layer is what made his art completely individual. Chakraborty elaborates, “He was an expert in creating a shell of naturalism while making brilliant use of his personal vulnerabilities, humour and anxieties in his craft, thereby making the act purely exclusive to him.” The “natya-chef” that he was, one would think that the artist was extremely meticulous in his preparation for a performance. Theatre artist Shekhar Chatterjee however says that the “always anxious Dwijen-da” was never someone who would focus too much before going up to the stage. “He would keep on insisting how he is nervous and not ready at all but just after the third bell rang, he would storm off to the stage and then put up an effortless performance with no trace of his previous anxieties…he is like a magician who hardly required any extra concentration before performing”, says Chatterjee. Meghnad Bhattacharya, renowned theatre actor and director of the group Sayak, adds that Bandyopadhyay’s ease at performing was also something that required the least amount of resources. He was someone who was never too worried about the extravagance of props and makeup. Bandyopadhyay could seamlessly transform into any character with nothing but the genius of his acting. His craft was elastic enough to go beyond material requirements.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWmbXDiAOUU&t=326s

A similar thought of focussing on the form to transform any content radically was expressed by Bandyopadhyay himself in an interview he gave on 2015 to Kahoon. He said, “I do want to create contents which have a lasting impact on the audience. However it is interesting to note that there is nothing called a bad content. It is the form that makes all the difference of presenting anything beautifully.” Bandyopadhyay’s form was his acting alone and it was indeed very uncomplicated and devoid of any excess. Sudeshna Roy, who had the privilege of casting Dwijen Bandyopadhyay in her yet to be released film Benche Thakaar Gaan, says, “Dwijen-da has taught me that acting should always be very simple. Overdoing it with excessive movements and unnecessary expressions never helps. Acting is something that comes from within, by being at par with your character.”

Dwijen Bandyopadhyay’s involvement in theatre also stood for his political ideologies of being a declared leftist. Besides creating a group like Samstab which made it a point to present plays representative of his politics, he was also vocal about openly criticising anything in the theatre world which was incompatible with his ideologies. Three years ago, after a show of Soumitra Chatterjee’s Kurbani at the Bharat Rang Mahotsav, organised by National School of Drama, New Delhi, I took his interview of Bandyopadhyay. While acknowledging the privilege to work with Soumitra Chatterjee, he said that theatre festivals which have a lot of sponsorship usually stick to calling groups which have already established a celebrity status of sorts. He indicated that had it not been for that particular play, National School of Drama had rarely thought of giving space to groups like Samstab. In the 2015 interview, he reiterated his scepticism of highly commercialised forums like theatre festivals which, according to him, “replicate the vices of a highly classist and consumerist societies” at the end of the day. He believed that such consumerist platforms make theatre susceptible to sponsorships and propaganda of the wrong kind. It takes away from the larger political purpose of theatre. Bibhas Chakraborty remarks that Bandyopadhyay’s insistence to stay true to his politics in his work derives from the tradition of theatre espoused by Mohit Chattopadhyay. Plays such as Bhutnath, Ei Ghoom or Tushagni, written by Mohit Chattopadhyay and produced by Samstab, represented the kind of politics Bandyopadhyay believed in.

While his friends and colleagues spoke with a heavy heart at this untimely loss, they were also hopeful that Bandyopadhyay’s tradition of an effortless yet meaningful performance would continue. Soumitra Chatterjee said, “While I cannot express the inconvenience Dwijen has caused our team by leaving so early, I have to admit that it was his involvement with our group that has enriched all of us, making us immensely hopeful of doing better work in the future.” In order to do justice to Dwijen Bandyopadhyay’s influence in the world of Bangla theatre, Shekhar Chatterjee declared that every year, on the 22nd of September, their group would honour a new theatre actor with the Dwijen Bandyopadhyay memorial award. This, hopefully, will be an attempt to look for a new actor in theatre who is inimitable.