The reports in the mainstream media of incidents of rape or sexual harassment occurring within spaces of higher education in India have been few and far between as compared to the almost daily reports of incidents of rape and gendered violence occurring across the country. It is universally acknowledged that the actual cases of sexual violence far exceed the reported cases (all over the world). The data collected by the University Grants Commission from institutions of higher education from all over India for the time period of 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017 reveals that 103 female students had filed complaints of sexual harassment. This number consists of only the students and only females, not people occupying other positions within academia and members of other genders. Even then, it is evident that this number, on a national scale is far too low. It cannot even possibly account for all the instances of sexual harassment leave alone other forms of gendered violence which are prevalent across campuses in the country.

The key word here, as indeed in statistics of sexual violence everywhere, is “reported”. Within reported instances, it has been seen that the incidents of acquaintance rapes phenomenally outnumber the incidents of rapes by strangers, at least in India. According to the latest data provided by the National Crime Records Bureau, 95% of the rape survivors knew the offenders. Also, conviction rates are much higher in the case of crimes committed by strangers as opposed to acquaintance rapes.

The discourse of rape is articulated within the (at times constricting) parameters of the victim/perpetrator framework. Adopting this framework to discuss issues of gendered violence is fraught with inadequacy, yet it must be adopted here while dealing with a normative idea of what constitutes rape. So, moving over to the scenario of gendered violence within university campuses, it becomes evident that here too in most cases, the victims have a higher likelihood of being acquainted with the offenders. To understand the reasons for the gap between the assumed-actual figures and the reported figures of rape and sexual violence in Indian campuses, one of the factors to be considered is this acquaintance between the victims and the perpetrators. How each of these entities is situated in the hierarchy within the academic structure determines to a large extent the nature of this acquaintance and the ensuing interaction and the power dynamics operating therein. The offender might be just another batch-mate, a senior or one’s teacher. This element of acquaintance also becomes a major impediment in the later stage of bringing the case to trial. In a regressive culture like ours, acquaintance is usually equated with consent. Leave alone intoxicated consent, which is a bone of contention in legal proceedings around the world. In most cases of acquaintance rapes, the proof of the absence of consent hinges on the victim and the verifiability of her statement.

Now we all know that the Section 376 of the Indian Penal Code, which pertains to rape, was significantly amended to put the burden of the proof of innocence on the perpetrator rather than the victim, in as far back as 1983. This had occurred following the Mathura rape case (1972), when a strong women’s movement had emerged to pressurise the judiciary into enacting major changes in the rape laws of the land. Chief among these was that the court would assume the victim’s lack of consent as a rebuttal presumption, once it could be established that intercourse had occurred. Hence, it would fall upon the accused to prove innocence rather than the victim having to prove their lack of consent. However, it can be seen from the rampant victim blaming in our public spaces and even in our courtrooms that the amendment has not entirely been a success. But surely, this would not be the case within the more liberal and progressive spheres of our academic spaces.

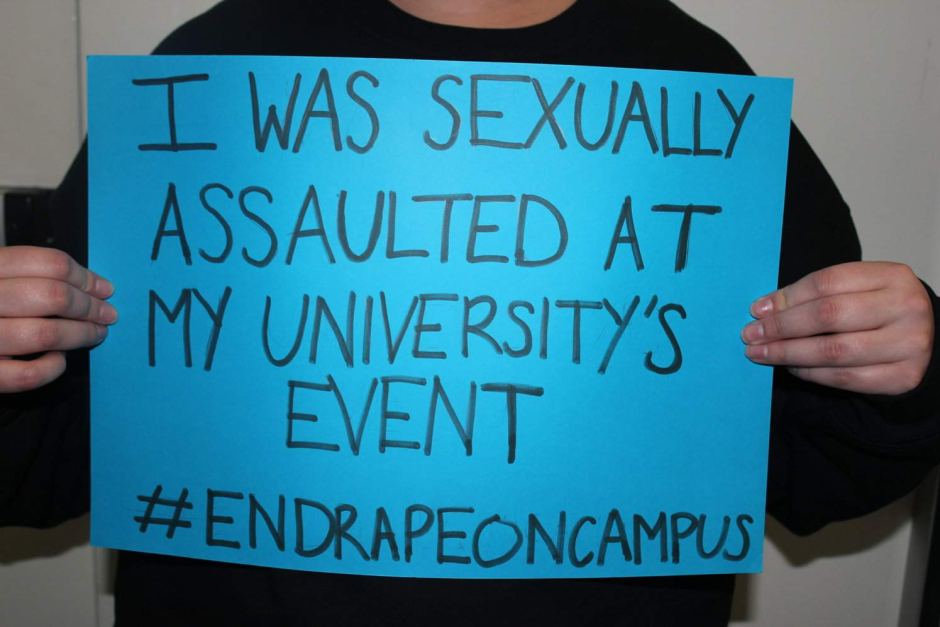

The verdict in the case against Brock Turner in the Stanford University rape case (2015) had created uproar. In the universities in the US, the institutional bodies at the university level, which were in-charge of grappling with sexual assault, had been failing regularly in doing so. In most cases the perpetrators were being let off easy even after being found guilty. On top of this, the same problem of cases not being reported to the authorities persisted. The reasons behind this unwillingness to report are closely linked to the reasons why such violence at all occurs within campuses. In India, most universities do not even have this luxury of a well functioning institutional body to deal with issues of gender violence. When these are set in place, then the unwillingness of the victims to report allows perpetrators to go scot free.

Where does this unwillingness to report instances of sexual violence come from? Many a times victims believe that the assault is not worth filing a complaint over. Then again, certain cases are not reported for fear of the repercussions. When a case of sexual assault is filed against any student political activist, one of the first questions invariably asked is about the political affiliation of the complainant. This gives us an idea about the general perception of credibility attached to accounts of victims/survivors. This is not even taking into account what the authorities would have to say about an incident of sexual assault on campus. The recent comments from the authorities in BHU regarding the assault of a young woman outside her hostel largely mimicked the usual victim blaming and shaming routine.

Rape is always a contested narrative, with the burden of proof falling squarely on the alleged victim’s shoulders. The perception of what does or does not constitute a ‘valid’ case of sexual assault is in itself very constricted. The narrative of rape and sexual assault necessitates the very water-tight boundaries of the categories of victims and perpetrators. These entities are necessarily understood within certain binaries of either having or not having agency. The pre-existing narrative of the occurrence of sexual violation is so constricted and exclusionary that once a certain narrative of abuse is unable to conform to the expected markers of a typical victim and perpetrator narrative, it does not find legitimacy.

This is where the complications arise in the long struggle to attain justice in the case of acquaintance rapes. In university spaces especially, the chances of sexual assault by a stranger is rare. Amongst entities perceived to be acquainted, the first barrier to attaining justice for the victim arises in the impediment of having to prove the lack of consent. The prevalent idea of what constitutes sexual harassment is narrowly defined and the role of who can be considered a victim and a perpetrator are also consequently exclusionary. For victims who are unable to access this normative narrative of rape, certain kinds of abuse and harassments get delegitimised. This closes off the means of seeking redressal.

This being the state of things it is hard enough for the victim to be able to take the decision to report a case against another student. If the perpetrator is someone who occupies a position of more power and more socio-cultural credibility than the victim, then it in itself usually acts as a deterrent for victims to report a case of harassment. In a lot of cases of sexual assaults on campuses there are no black and white instances of rape and violence, like the oft cited Nirbhaya rape case. The considerations of whether an act of assault or harassment was bad enough to pursue this path, becomes a concern for the victim. Whether this incident would fit into a normative idea of what could legally constitute an assault or not is considered. If at all this is traversed and the victim decides to report the case, then the almost insurmountable problem of proving the lack of consent rears its ugly head. The meticulously worded UGC Handbook on Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace definitely does not help in this scenario. While the situation differs from university to university, even with campuses with an active body stipulated for dealing with issues of gender, these concerns and impediments do find their way in. The prevailing normative narratives of rape accompanied by the power structures within which the narrators have to define their plights are becoming a major barrier to not only seeking justice but even the mere narrativising and expressing of accounts of sexual violence.

What has happened in the wake of the publishing, through a Facebook post a list of purported sexual predators, is very different. This is a scenario where the alleged perpetrator is merely named. Moreover, these are alleged perpetrators who have some of the highest levels of socio-cultural, intellectual and political sanction and validation within the academic space. Also, the narrative of each and every incident of violence has not been presented, and thus the question of that narrative conforming to certain pre-determined ideas of what constitutes rape and sexual violence has not arisen. These claims of abuse can be invalidated at the outset, as they do not follow any of the markers of a formal report or complaint. So it is indeed a ray of hope that even in the face of such impediments these claims of victims/survivors have found such legitimacy amongst seasoned academics. This sort of a legitimacy which is denied in our patriarchal academic spaces could of necessity only be found within a feminist space. The very naming of the alleged perpetrators has been enough. It has been successful enough in implicating and been deemed damaging enough to the alleged perpetrators (in the absence of publications of proof and evidence) to such an extent that an immediate appeal was issued to do away with this mode in its entirety.

One end of the spectrum consists of victims who are advised to refrain from talking about sexual assault as it would ruin their and their family’s reputation. The journey to the other end of the spectrum where the anonymous victim is asked to refrain from naming her alleged perpetrators has been a long one. The concerns of the harm to her reputation can be done away with due to the anonymity (which would not survive the publishing of every incident and narrative of sexual violence), which leads to the concerns with the harm to the reputation of the alleged perpetrator. In yesteryears, we have seen how allegations of sexual violence have been inconsequential to people in power in our country, many of whom have gone on to hold prominent positions in government. That this mode has had so much consequence is indeed a testament to the long way that the feminist movement has brought the struggle against gendered violence. The appeal to remove this mode expresses its concern with the delegitimisation of other modes of seeking justice. It is to be hoped that these complainants do find their way to this justice. However, the road to Institutional justice, especially after navigating the hierarchies and power structures within the academic space, will be arduous at best. If all else fails the hope for “natural justice” should provide some respite to the survivors.