At the root of the controversy over the release of the Hindi feature film Padmavati is, first, the saffron brotherhood's interpretation of history with a pronounced anti-Muslim bias and, secondly, the Bharatiya Janata Party's overt and covert attempts to whittle down institutional autonomy.

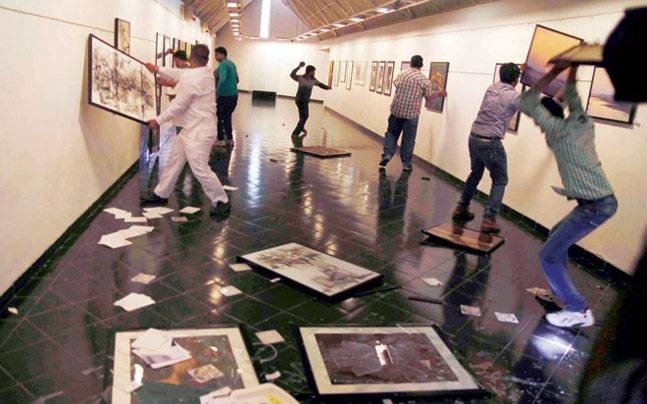

Even if the BJP's seemingly political use of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) is a continuation of the practice of its predecessor which made the Supreme Court call the CBI a "caged parrot", the party can be said to have broken new ground by letting vandals of the Hindu Right vent their anger against Padmavati and, thereby, undermining the authority of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC).

In this case, too, there are precedents as when the Congress objected to the film, Indu Sarkar, because of its focus on Indira Gandhi. But the saffron offensive against Padmavati is making a greater impact because of the clout which the Sangh Parivar affiliates enjoy in view of their proximity to power.

It is obvious that if they are not checked, not only will the authority of the CBFC be diminished, but also the board will be wary in future of clearing films dealing with history or issues which are close to the Parivar's heart. Politics will, therefore, virtually take over the board's functioning.

What is more, the filmmakers themselves will be dissuaded from touching subjects which may be deemed sensitive and deal instead with safe, insipid topics. Such a state of affairs will be unfortunate at a time when Bollywood has been breaking away from the earlier productions with their song-and-dance routine and predictable storylines which were far removed from reality, except in a few exceptional cases which came to be known as the parallel cinema.

Not long ago, it was expected that the directors and producers will be able to breathe easily after the previous censor board chief, Pahlaj Nihalani, was unceremoniously removed so that he could no longer run amok with his scissors in accordance with his saffron whims, as in the case of reducing the duration of a kiss in a James Bond film or ordering 89 cuts in Udta Punjab or not clearing Lipstick Under My Burkha at all.

But any hope that the new board will be allowed to exercise its judgement in peace with the support of the Information and Broadcasting Ministry has been belied if only because the opponents of the idea of letting the artistes pursue their craft unhindered are far too influential politically.

The decision about what the audience will be allowed to see is being taken not only by the self-appointed guardians of culture but also the ministry which has banned two films — S Durga and Nude — from an international festival in Goa apparently because the letter "S" in S Durga stands for "sexy", which is too strong a word for bureaucratic ears, and Nude is out for obvious reasons.

While the rewriting of history books is proceeding apace with Rana Pratap winning the battle of Haldighati against Akbar on the pages of the textbooks printed in Rajasthan, the Hindutva storm-troopers are laying down the rules on how historical events are to be shown on the screen.

India has already seen the exiling of a reputed painter, M.F. Husain, who was hounded out of the country by saffron vigilantes who were displeased with his depiction of Hindu deities.

It will be a sad day if filmmakers, too, have to leave the country or shoot their films elsewhere, as in the case of Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children, which was shot in Sri Lanka.

The standard explanation for demanding cuts in the films is to ensure that the sentiments of the people are not hurt.

It was for this very same reason that Galileo had to disavow his thesis about the earth moving round the sun since such an assertion offended the feelings of the church and the laity in medieval Europe.

It took the church 350 years to apologise. There is unlikely to be anyone in the ruling dispensation or even in the opposition who will be courageous enough to say that the question of whether religious or cultural sensibilities are being hurt cannot be settled on the streets but should be left to the institutions to decide or, as a last resort, to the judiciary to determine with the assistance of scholars.

The saffron ire against Padmavati is apparently over the belief that the film will be unable to do justice to the heroic reputation of the queen of Mewar, a legendary beauty, who killed herself rather than be captured by the invading army of Alauddin Khalji.

Although no one, except the censors, has seen the film, the Hindu Right is patently unwilling to take the chance of an erroneous presentation. So the group has donned battle armour to save the fabled queen (real or fictional) 700 years after her death — this time from filmmakers — and is issuing blood-curdling threats against the director and the leading actress.

If accurately presented, the turbulent period of early 14th century Rajasthan can be the subject of a rivetting drama. But whether cinema-goers will be able to see the film is still uncertain.