The town that is called Ayodhya in Valmiki’s Ramayana, as well as today, was known as Awadh in pre-British times. Tulsidas in his Ramcharit Manas called it Awadh-puri. It was a large city, capital of the province that was also called Awadh. It had, therefore, a large Muslim population. So it was that when Babur established the Mughal Empire in India in 1526, and Awadh or Ayodhya fell into his hands, his governor Mir Baqi built a large mosque there, which came to be known as the Babri Masjid. The fact of its construction was proclaimed in two Persian inscriptions, one inscribed on the pulpit and the other, a longer one, on the gate. Neither of these inscriptions says anything directly or indirectly about the mosque being built on the site of a destroyed temple. Had that really been the case, Mir Baqi should have surely proclaimed it: there was no reason for him to have remained silent about it.

Ayodhya’s reputation as the birth-place of Lord Rama, in fact, developed very late, well after the Babri Masjid was built. Sanskrit inscriptions set up at Ayodhya, or such as a mention of the place from first century BC to twelfth century AD show no connection of Ayodhya specifically with Lord Rama, who is not even mentioned by name in them, whereas other deities like Vishnu, Shiva and Vasudeva (Krishna) are. The first known Sanskrit text to place Lord Rama’s birth place in a locality of Ayodhya is the Skanda Puråna, which has varied versions, but is not earlier than 1600, to judge from the text’s internal evidence. Among more than 30 sacred sites in Ayodhya, it names one as Råmajanma. It is only in the latter half of the eighteenth century that we read in the account of the European traveller Tieffenthaler, who visited Ayodhya some time before 1765, of the allegation that a temple was destroyed to build a mosque on the site by Båbur, or Aurangzeb. Since the two inscriptions referred to the reign of Babur, many Muslims also came to believe that he not only built the mosque (though it was actually Mir Baqi) but did so after destroying a temple.

The situation thus became ripe for a communal clash, which occurred in 1855. The place was then under the Nawab of Awadh, whose officers settled the issue by letting idols being placed outside the mosque, on what came to be known as Sita-ki-rasoi. A trust (waqf) was also created for the mosque.

In 1884, the case came before Pt. Harkishan, sub-judge, Faizabad, and then in 1885, on appeal before W Young, judicial commissioner, Awadh. Both decided in favour of Muslim possession of the Mosque while Young allowed also the Sita-ki-rasoi to be retained by Hindus. The property issue was thus settled in the eyes of law.

The matter should have remained settled, but as communal tensions revived in the 1930s, a Hindu crowd broke into the mosque and damaged the pulpit, destroying the Persian inscription set up on it. However, the mosque was recovered by the Muslims, and their prayers continued in it till December 1949.

On January 30, 1948 Gandhiji was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, a follower of Hindu Mahasabha and RSS, and the RSS was put under ban. After some obviously insincere assurances by its leader Golwalkar, the ban was lifted in July 1949. Immediately thereafter, the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha looked around for an issue to try to stir the communal pot again so as to revive their base. One such issue was found in the Babri Masjid.

During the night of December 22-23, 1949 the locks of the mosque were broken open and the idols of Sita-ki-rasoi transferred to a central position within the mosque near the pulpit, so that Muslim Namaz or congregational worship could no longer be performed there. Despite a police report describing the whole incident, it took the Indian judiciary sixty-one years to recognise that the idols did not fly of themselves into the mosque, but were put into the mosque by human hands. (This recognition came through a subsidiary judgement by the Allahabad High Court delivered on September 30, 2010).

Despite strong positions on the matter taken by both Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and Home Minister Sardar Patel, the UP Premier Pundit Govind Ballabh Pant showed no inclination to uphold the law, by returning the idols to their original position and restoring the mosque to Muslims. The secretary of the local district Congress committee Akshay Kumar Brahmachari, after failing to persuade the authorities to restore the mosque to Muslims, went on a 31-day hunger strike in pursuit of his cause (August 22-September 22, 1950), breaking his fast only after urgent appeals to him were made by Muslim leaders.

The matter then lay dormant for over three decades. The mosque remained closed to both Muslims and Hindus, with idols remaining inside. In 1980 the BJP, being the old Jan Sangh under a new name, suffered a great defeat at the general elections. Its leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s slogan of Gandhian Socialism deceived only a disappointing few. So a turn to rabid communalism was again put on its agenda. In 1984 the Vishwa Hindu Parishad was formed, with the slogan of building a Ram Temple at the site of the Babri Masjid being put at the top of its agenda.

So the issue was again revived and on February 1, 1986. KM Pandey, district judge, passed an order unlocking the mosque for Hindus to enter the mosque and offer puja to the idols, while Muslims continued to be barred from entering the building. The learned judge wrote in his memoirs that a monkey (presumably Lord Hanuman or his emissary) came especially to hear his judgement and to thank him!

By this judgement, duly put into effect by the late Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress government, the Babri Masjid was virtually converted into a temple, to the exclusion of all Muslims. Thus encouraged, the BJP and Vishwa Hindu Parishad now launched their campaign to physically destroy the Babri Masjid and build a Ram Temple at its site. This was marked by the shilanyas movement, bringing bricks to the site and laying foundation for the temple on November 9, 1989. Next year, the Rath Yatra undertaken by LK Advani, during September-November 1990, was followed by a physical attempt to destroy the masjid by the kar-sevaks. This was prevented only by the determined action of the Samajwadi Party government of UP at that time, leading to the death of some kar sevaksin police firing.

Right from 1986, the CPI(M) and the democratic and secular elements in the country had been constantly demanding that due protection be extended to the Babri Masjid. The Indian History Congress at its successive annual sessions demanded that the Masjid be declared by the Government of India a protected structure under the Ancient Monuments Act 1958, but to no effect. Such lack of action opened the door to the masjid’s destruction.

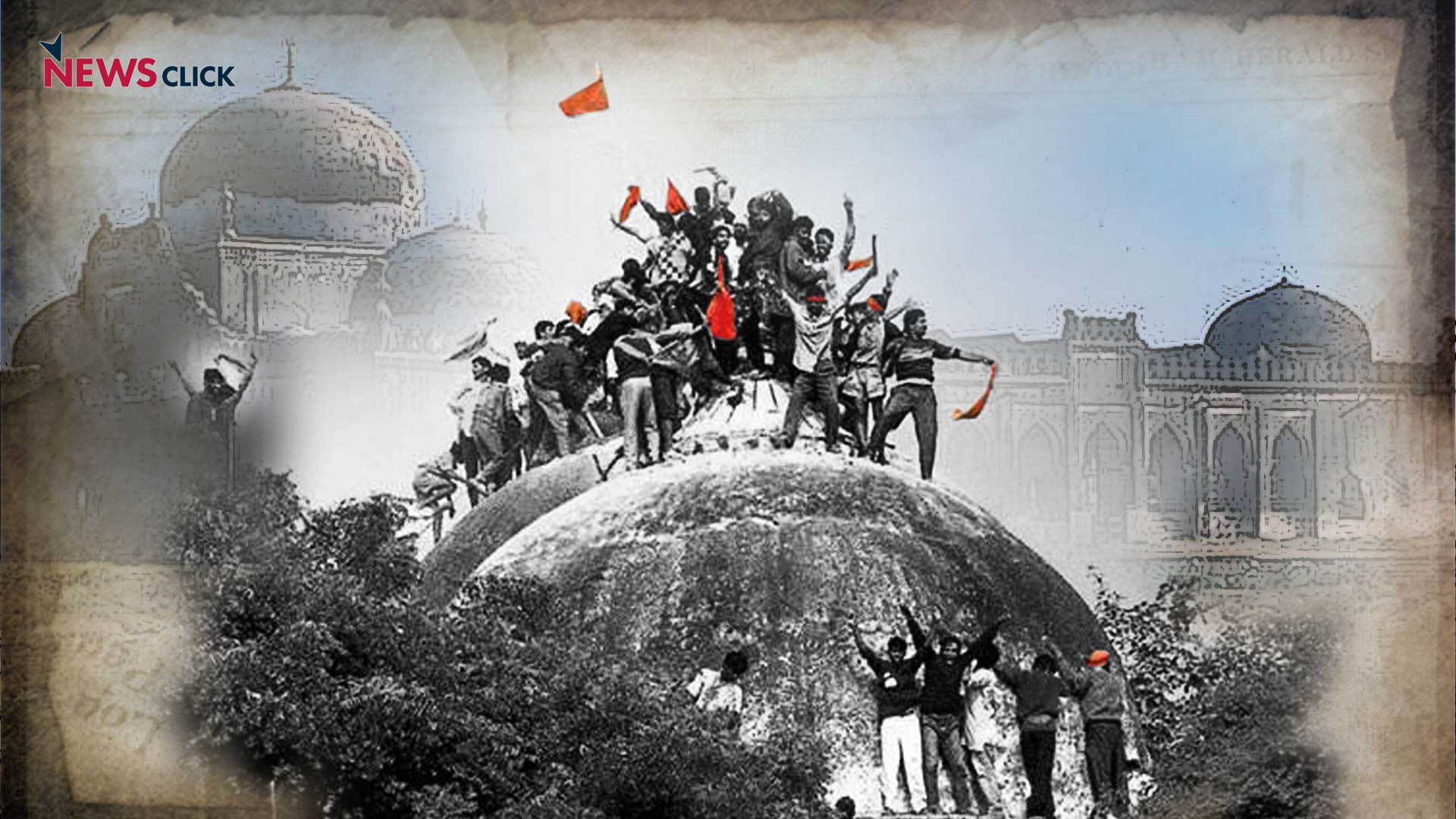

In June 1991, the BJP-led government was installed in UP and now the plan to destroy Babri Masjid began to take concrete shape. Despite the open declaration that their intention was to destroy the Babri Masjid, thousands of kar-sevaks led by LK Advani and other BJP leaders, were allowed to assemble at Ayodhya, and on December 6, 1992, without any intervention of the police, let alone the army; they were given full 24 hours or more to destroy Babri Masjid and also remove and then re-install the idols.

Perhaps, neither the BJP nor Narsimha Rao’s Congress government was prepared for the public revulsion that the crime aroused. Parliament proceedings were stalled for several days. The media generally condemned what had happened as a blot on the good name of the nation. The central government was compelled to dismiss all the BJP state governments including, of course, that of Uttar Pradesh. Yet although 25 years have now passed since the destruction of the Babri Masjid, a grossly criminal act, in violation not only of the law, but also of orders of the Supreme Court and High Court, not a single culprit has been brought to justice or put in prison.

After December 6, 1992 the next stage of the movement began, to build a Ram temple at the site cleared by the physical destruction of the Babri Masjid. The dispute over possession of the land under Babri Masjid and its precincts was obviously a property dispute, and the main point should have been about who was in possession of it for over twelve years before the violent intrusion of December 22-23, 1949. However, the Allahabad High Court (Lucknow Bench) decided in 2010 to judge the issue on its own manifestly erroneous reading of history and archaeology, and assigned two-thirds of the land, made vacant solely by the criminal act of December 6, 1992, to the Hindu parties. How ill-founded the High Court’s reading of history of the mosque has been can be seen in the detailed rebuttal (History and the Judgement of the Allahabad High Court) published by SAHMAT, the organisation of democratic intellectuals and artists, within three months of the judgement, in December 2010.

An appeal is now pending in the Supreme Court. Without meaning any disrespect to the judiciary, it must be acknowledged that its performance so far does not instill much confidence in its ultimate decision. But to us the final arbiters are the Indian people. While observing the 25th anniversary of Babri Masjid’s destruction, one must recall Comrade Jyoti Basu’s firm commitment to the secular position in respect of the Babri Masjit dispute. Let us try to the best of our capacity to convey to all whom we can reach as to what is at stake here – the very honour and democratic values of the Indian nation.