Home. The word is used so casually by most of us. What the word stands for is also easy enough to identify. A house or a room; a village or a city or a country; a couple of people or more; a language or two; food, maybe some landscapes, myths and tales. In other words, everything intimately tied with day to day life; the familiar; the taken-for-granted.

For some people, home is not so easily mapped. Home may have been pushed off the world’s map so it resides only in memory and imagination, both shifting territories. Or home could be a many-layered place, one layer sinking into another so not one can be confidently named.

It is not as if that these homes do not have the quotidian attached to them. Even these troubled homes may host a parent, a childhood friend or some other sustaining memory; a house or what may pass for a house; and the land itself. But these commonplace features of home have grown distorted. The land has been ravaged. The home’s soul, a secure sense of belonging, has been disfigured.

Three different books recently published by Women Unlimited in India have home as their raison d’être. Seeking Palestine is, as the title suggests, in search of Palestine; Dreaming of Baghdad recalls the Iraq of the 1970s; and The Tiller of Waters is set in a Beirut torn apart by civil war. But all three probe the human costs of a home no longer home. Where is home when it is an occupied and brutalized place? Or torn apart by civil war? Or a place of prisons run by a dictatorship? To describe these broken or lost homes, to understand why they are still homes, why they need to be homes, the three books take on the notion of exile, internal and external. They confront the past, the powerful ghost that haunts all those who have been displaced. They recognize the need to reconstruct home — in words and in personal and political action – and affirm the multiplicity of the places they come from. Most of all, they give voice to the aspirations of those who can only go back home if they search for it and locate it afresh.

Palestine is obviously the sharpest example of both the loss and hope that accompany such a search. For homeless Palestinians, whether they are still in Palestine or far away, the poet Darwish’s idea of “cultivating hope” could be a credo. They have to seek Palestine so they may hope; they have to hope so they can find Palestine. It is impossible to talk of Palestine – historic Palestine, occupied Palestine, or the idea of Palestine in the future — without viewing the multiple meanings held by the notions of home, exile and dispossession. Rana Barakat, one of the contributors to Seeking Palestine, gives us an idea of this complex task: “Palestine-in-exile is an idea, a love, a goal, a movement, a massacre, a march, a parade, a poem, a thesis, a novel and yes, a commodity, as well as a people scattered, displaced, dispossessed and determined.” It is all this; but a home must be ordinary if it is to be a home. Raja Shehadeh and other writers speak of their desire to move Palestine from a place of “insistent memory” to a place where “a robust Palestine can be ‘nothing more… than home.’ ” But this has not yet happened. Palestine still resides in conditions of crisis; of statelessness, of transience. Most of all, it resides in the Palestinians, wherever they are.

What does it mean to be Palestinian? The essayists, poets, novelists, critics, and memoirists writing in Seeking Palestine reflect on this question and come up with individual and collective experiences of seeking, waiting, living for, and being or becoming Palestinian. For many, writing Palestine is an exercise in “imagining rather than representing” home. It means disappeared villages, erased histories. It means going back home with a tourist visa; indeed, entries and exits comprise a recurring theme. For Rana Barakat, “home is provisional” given its foundation in “the tragic indignity of exile” and the “unrealistic” resistance of this indignity. For Mourid Barghouti, being Palestinian means being in suspension. In an insightful piece, he illustrates, poetically, both reality and aspiration:

The suspended blob of air in which we… are swinging is now our place of exile from this earth… This bubble of air is the unyielding Occupation itself. It is the rootless roaming of the Palestinians through the air of others’ countries… We sink upward… I want my high standing to be brought low, Grandmother. I want to descend from this regal elevation and touch the mud and dust once more so that I can be an ordinary traveller again.

For Susan Abulhawa, being Palestinian is “a state of enduring expectation.” Abulhawa, in an engaging and candid personal essay, lists some of the inevitable experiences that come with the Palestinian tag:

To be alone, without papers, without a family or clan, a land or a country means one must live at the mercy of others. There are those who might take pity on you and those who will exploit and harm you. You live at the whims of your hosts, sometimes preyed upon and nearly always put in your place… But there are particular beauties and peculiar strengths that can only be found in the trenches of such a life – like the ability to hold your head high, even when someone has their boot on your neck; the wisdom to do whatever it takes to get an education, even when you’re denied a school; the freedom of shedding shame and living one’s truth, no matter how messy, without apologies;… the victory of a heart that does not succumb to fear or hatred or bitterness.

In other words, being Palestinian means being in a limbo — dispossessed, disinherited, exiled. It means belonging is denied or controlled by the occupier. But seeking Palestine also involves resistance in myriad ways. How does this happen? How do people survive being a refugee in someone else’s country and even in their own? Among the modes of survival these fifteen writers illuminate for us are humour, wry and biting in turn; apathy, anger, longing; the use of words, of memory; the living out of intensely political lives, stoking the idea of Palestine so it may flame into reality. In this limbo of banal as well as exalted despair and hope, “Palestinians have been waiting at borders for nearly a century now.” Raja Shehadeh and Penny Johnson, and the writers they have got together for this volume, have done a fine job of recounting this waiting, and the struggle of both imagination and action to put an end to it.

Being haunted by the past, trying to come to terms with it; at the same time, fingering it obsessively, trying to find hints of truth by reconstructing the past through narrative. Like the Palestinians writing of home and exile, Iraqi activist and writer Haifa Zangana mines memory for personal and political understanding.

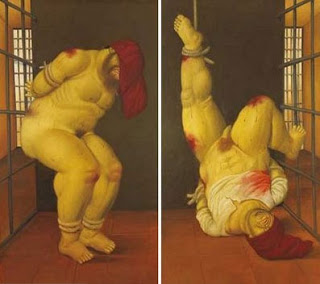

Haifa Zangana was among the group of radical activists who mounted courageous opposition to the Baath Party and its leader, Saddam Hussein, in the 1970s. Zangana was twenty years old when she, like many of her comrades, was imprisoned and tortured. She was in a palace turned into a detention centre for political prisoners; then in Abu Ghraib, “an ordinary prison”; and finally in a prison for prostitutes. When she was released after six months, her face was covered in sores, she cried for any tender word or gesture: “For a whole year afterwards, I was reduced to an entity closed in upon itself, absorbed in remembering that howling, remembering the dead.”

It made Zangana write Dreaming of Baghdad, a testimonial marked by its intelligence and fierce honesty. The account is enriched by a poetic style that is blunt about facts, truths and possible truths, but skilfully elliptical in uncovering these. There is not one sentimental word in this memoir; but there is a great deal of pain, self-questioning, love. And commitment. That the latter has endured is evident in Zangana’s political stance post-2003. Much to the astonishment of Western interviewers used to black and white accounts of pro-Saddam and anti-Saddam positions, Zangana, imprisoned and tortured during the Baath regime, has said in no uncertain terms that the occupation and its consequences have been infinitely worse for the Iraqi people than the Baath regime or life under sanctions.

Iraq author says status of women has deteriorated since 2003 US-led invasion…

Clearly a memoir by such a person cannot be an ordinary one. The intelligence and skill of the narrator are apparent right away:

I wrote (this book) at a time when I didn’t want or wasn’t able to deal with memories of what had happened to me in prison. I wrote it while I was living in exile, missing my family terribly, believing I would never return to live in Baghdad again. I wrote it during the Iran-Iraq war, at the height of Saddam Hussein’s popularity in Iraq, Arab countries and the West. I wrote it in first person, as a record of my memories, and in third person, as I often saw myself, as if I were standing outside of my own life, trying to remember things and events as correctly and completely as possible. I wrote it with the hope that I would not betray the memories of the people with whom I worked or was imprisoned. I wrote it about her – not always about me – because I wanted to avoid the illusion of self as the centre of events or history.

Personal wounds and scars, catharsis, loneliness, dislocation, dissenting voices, location of personal experience in a larger political and historical context: all these strengthen Zangana’s intention and her actual narrative. There are the horror stories to be expected of any prison literature written about a repressive dictatorship. Consider her last encounter with a young comrade given to laughter:

My interrogator signalled to the man standing at the door to let the first terrorist in. They brought in a disfigured mass of flesh, carried by two men as if it was not able to support itself… I recognized Fouad’s voice… when I die, I will take with me something of this world. That thing will be the image of Fouad’s tortured body. The image of a young man transformed in ten days into a mass of unseeing, unhearing flesh. The image of an idealistic, beautiful dreamer disfigured by torture.

Zangana’s memoir is equally relentless in its examination of the survivor’s life. Or half life. The survivors spend evenings talking about the past; they talk about each other as if the person being spoken of is not there; they speak of each other as the young men and women they once knew; the “only living presence among (them) is the past”. It is not just guilt at having lived while others died. It is not just the repetitive questions of what could have happened to whom that exacerbate the feeling of exile. There is also the unspoken question about a possible personal and political renewal: will they ever be able “to rekindle their dreams”?

Perhaps the most refreshing quality of Dreaming of Baghdad is its confrontation of hard questions about all truths and possibilities, no matter how close to the bone. The first person Zangana considers the third person Zaifa who joined the radicals in the first flush of youth. Words like killing and torture were, possibly, only words then. But now that “words have been made into matter” and ideology humanized with actual experience, the older Zangana’s introspection alters political perspective in subtle and complicated ways. The world is not divided into victims and torturers who play the same role forever. With her deep sense of history, Zangana asks of herself and her fellow survivors: “Is there any guarantee that we, too, will not wear the faces of the torturers in the future?”

Zangana’s book is an important assessment of the seventies in Iraq; it also offers significant insights for assessing Iraq today. In his moving Foreword to the English edition of the book, Iranian scholar Hamid Dabashi says,

How many more books like this revelatory testimonial will we have, will we need, before the record is set straight – before we know what was Baghdad, whence Iraq, and who the Iraqis were before they were brutalized by the combined malignancies of Saddam Hussein and George W. Bush? Zangana’s voice is at once elegiac and defiant, memorial and revelatory, sad but surreal in its visionary recital of what was and what might have been.

Top: The families of Iraqi political prisoners run into Abu Ghraib to find their relatives after Saddam Hussein declared an amnesty in October 2002.

Top: The families of Iraqi political prisoners run into Abu Ghraib to find their relatives after Saddam Hussein declared an amnesty in October 2002.

Bottom: Hundreds of Iraqis whose relatives were held in Abu Ghraib demanded to see them after the release of pictures showing prisoners being humiliated by American forces.

The seeking individual has to be seen with clear eyes; but this is a meaningless exercise if disconnected from the layered contexts of peoples, lands, nations. Seeking Palestine and Dreaming of Baghdad underline this. And so does Lebanese writer Hoda Barakat through her novel, The Tiller of Waters.

Barakat weaves together numerous linked narratives, but three of them emerge as the major strands. One is the city and its many avatars; another is cloth and its journey from linen to the “decadence” of “chemically forged” textiles; and the third is the lost individual, a man on the edge of madness in a devastated Beirut. The three threads are parallel exercises of reconstruction that come together through the hyper-vision of the hallucinating narrator.

The most powerful of these strands is that of the city. A city shifts; it grows and prospers, there is a brief glimmer of glory. Then it is laid to waste by invasions and wars, plague and earthquakes, siege and bombardment. At one point it even becomes a deserted village. But it is reconstructed. The cycle of devastation and reconstruction makes the city a palimpsest: it “does not advance in time but rather in accumulating layers, a city that will sink as deeply in the earth as its edifices tower high.”

“The past is the present is the future” says Haifa Zangana in Dreaming of Baghdad, as if summing up the impulse behind these three books. The Palestine recalled by some of the essays in Seeking Palestine no longer exists. Zangana’s Baghdad of the seventies is gone. So are many of the Beiruts Hoda Barakat describes in The Tiller of Waters. In an interview with Al-Ahram Weekly (1999, http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/1999/457/profile.htm ), Barakat has said, “No, I have not made my peace with Beirut and I think it's too late, because the Beirut I need to make my peace with is no longer there." But to make sense of today’s Palestine, Iraq and Lebanon, to imagine them tomorrow and move toward those visions, multiple pasts, presents and futures must intertwine. And this is something all three books capture well enough to convince us.

A postscript about the publication of these books in India. In our market ruled days, the real point of publishing is often obscured. The arabesque project of Delhi based publisher Women Unlimited reminds us of the small and independent publisher’s place in our lives as Indian readers. Despite historical links with the Middle East, our post-colonial education has left us largely ignorant of modern literatures in Arabic. Our neo-colonial present, and the new love Official India has developed for Official America and Official Israel, dims the chances of rectifying this ignorance. But through these books, Women Unlimited has given us literature that seamlessly blends the personal and political in parts of the world in which we have a stake.

The text of Homeward Journeys was written for the July 2012 issue of Biblio: A Review of Books, New Delhi.