Who is the (YOU?)niverse of a University? Is it possible to talk about the University today? If so, HOW? Is there an idea of University in India? To be, or not to be, able to talk about the University is, in no way, solely dependent upon the system of “knowledge” that is acquired through rigorous academic investigation — though a critical eye is indispensable — or through meta-theoretically articulated pedagogical expenses, but, as Jacques Derrida argues, Today, how can we not speak of the University? It is, perhaps, at this moment of Indian educational history that this question holds as much water as never before. The question is a reflection of how a systematic attack on the idea of the University curbs the academic freedom of the intellectual and political sphere, freedom that is the building block of the University. The space of the University is no place for hypothetical contamination, with academic excellence being measured on the basis of mere presence within the four walls of a class room, which is but what academics might be conceived to be. The University is a space of critical and analytical engagement with issues pertaining to faith, an informed compliance with truth in the idea of what constitutes a University. But, sadly enough, a deliberate attempt to infantilise the idea of higher education in India is on the rise, where a faith in the Humanities of Tomorrow seems bleaker than ever.

The guiding principle of any University in the contemporary times is predicated upon the idea of a “modern University,” which is democratic in its outlook, guarantees academic freedom, and ensures an “unconditional freedom to question and to assert, or, going still further, the right to say publicly all that is required by research, knowledge, and thought concerning the truth.” (Jacques Derrida). But, critically speaking, unconditional freedom should not be interpreted to mean freedom without any conditions whatsoever, because freedom is premised upon larger costs of struggle and resistance. The unconditionality of resistances and struggles are rooted in being unconditionally unapologetic about the manufactured ideas of truth. The relationship between the teacher and the student is not a hierarchical one that, in an “always already” condition, assigns power positions as dominant or subservient; instead, it should be one of transference with an eye for learning and critical engagement. That the teacher “knows more” and the student “knows less” is a reductive way of doing academics, although, at a more apparent level, the teacher, by virtue of securing higher educational standards, becomes a teacher per se. Nevertheless, a reiteration of that academic position, in the process of learning, becomes nothing but a mere acknowledgement of the privilege that is unequivocally tied to the chair one holds and not based on how much or what it is that one knows. It can never be empirically measured as to how many ounces or “spoons’” of knowledge make one a “teacher” and the other a “student!” Students are also teachers themselves, since the one who “teaches” a text plays a limited role. One also has to teach one’s own self, otherwise, one can never become a student, let alone a teacher. Teachers too, remain students throughout their lives, since epistemological and pedagogical modes entail no teleological understanding in academics but one that is always deferred ad infinitum. The purpose is not to engage in any abstract cyclical notion of who is a teacher or who is a student, since it would not make pedagogical modes of learning different than what it is. Truth, nevertheless, speaks in the faith of being utterly unconditional, since there are no material conditions that decide the making of a teacher and student differently. Undoubtedly, hierarchies are bound to exist in any structured order, the academic world and that of higher education is one among several other establishments. While it can be said that that a University without conditions does not exist, the fact of its non-existence does not mean that it cannot exist or should not exist. The essence of the University lies in its virtue of being universal; all embracing; in its being, perhaps, the ultimate place of resistance and critical enquiry against appropriative gestures of dogma and force. The politics of unconditionality, if argued extra-diegetically within the space of the University, are not conditions bereft of conditions but rather conditions that are unconditionally disassociated with conditions of compulsion and authority. Herein an interventionist move is necessary with respect to the issue of compulsory attendance that is being imposed by the administration in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). It becomes necessary to ask certain questions, especially at this moment of terrible crisis in the University. How does one get to decide what is minimum attendance? Who gets to decide that, and how? If attendance in the classrooms should count, then why not count the hours of labour one puts in the library? Or, on archival research? Or, while attending conferences and seminars? Does full attendance in the class ensure full participation in the class?

To look for models of attendance in foreign countries becomes nothing but an ineffective validation, evoked simply to reassure the administration that the recent order regarding compulsory attendance is not draconian. Frankly speaking, attendance was never an issue in JNU. My association with the University, as a student, for the past eight months has revealed how students come for even 9am classes, and sit on the floors of the classrooms in case there is a paucity of seats. A few days back, a talk was organised by the Centre of Historical Studies. Patrick Olivelle, an eminent Indologist, came to deliver a lecture. The lecture was attended by so many that the hall was completely full, with scores of people standing for more than an hour.

But, one may argue, why not mark attendance if you are present for classes? What is the harm? The harm lies in the fact that that there is no need of it. This reminds me of the phrases, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” That’s the trouble with government (read administration): Fixing things that aren’t broken and not fixing things that are broken. The whole point, of the administration issuing the dictum of compulsory attendance, seems to be to create an environment of tension and panic, something that was not required at all. I have had personal experiences where people ask me, “Why involve yourself in protests all the time rather than getting involved in pragmatic goals like studying and looking for jobs?” All the response I have to this can be condensed into a single question — How? If protests are seen as unnecessary, then, my response is, was compulsory attendance necessary?

Let me leave my philosophical and critical stance at bay, for the moment, and look at the empirical details that would prove how crisis is manufactured like a vocational course in the University.

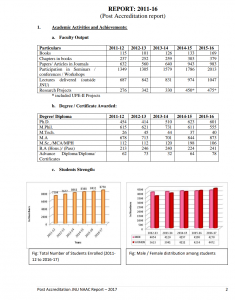

The National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) Report of 2017, which is available on the University website and presented above, indicates no significant lacunae in the academic excellence of the institution. Moreover, the NAAC accredited JNU with A++ grade (which is mentioned in the main University website), the highest grade conferred by the NAAC. The national and international rankings are also well documented in the report. But, what is not documented is the whimsical nature of the administration and its farcical attempt to ensure academic excellence through compulsory attendance. For instance, the Centre for English Studies, of which I am a part, inspite of being ranked among the top 100 departments in the Times Higher Education Rankings, has not been provided with M.Phil/PhD seats for the past two years; this is in spite of the availability of twelve seats in the Centre this year. There are other departments too, with similar experiences.

The so called practicable issue of Attendance would seem all the more impracticable if the motives behind the forceful attendance system are probed at a greater length.

The above is the latest circular issued by the University

Perhaps unnecessary to “some” but unavoidable for “few,” some questions need to be asked! If one’s academic excellence is solely based on their presence in the classroom, why should attendance affect fellowships and/or scholarships? Why should anyone’s “physical” (sadly enough, not mental) presence or absence from class affect their Merit Cum Means (MCM) Scholarship, which is disbursed to meritorious but economically unprivileged students? Should someone who is in need of urgent medical care be left uncared for only because they fail to meet 75% of compulsory attendance? I am myself a resident of a Hostel in the University and no such order of compulsory attendance was made a criterion for admission in the hostel. How or why should attendance be seen as essential for one’s residence in the hostel? The answers are perhaps more than self-explanatory but the questions seemed necessary for critical intervention at a time when the personal, as well as academic, freedom of the students are at stake.

To reiterate Jacques Derrida’s question, I would like to ask, does JNU, today, have what is called raison d'être? That is, “reason to be.” What does “to be,” in a University, mean? When the issue of compulsory attendance — along with its concomitant ramifications in terms of forceful withdrawal of scholarship, de-registration, and fear of loss of hostel facilities — have reduced the students to “bare lives,” as Giorgio Agamben called it, all faculties of reason, being, existence, freedom, and resistance should be directed only towards the idea of academic freedom, which is inalienable from the lives of students in the University. The surveillance in academic learning through compulsory attendance destroys the very idea of research, for which JNU is known. The investigative and epistemological methods in research can never be confined within the four walls of the classroom since any intended practice of learning and knowing can never infer and reflect upon the imaginative idea of the society we live in. Reality is far more cruel and torturous. As researches and learners, we do not live in a society in isolation, but, the society also lives within us and outgrows us. A dialectical relationship is the bedrock of academic learning and, perhaps, the future of higher education in India. But, increasingly, constant efforts are being made to stultify academic learning within the University space and bring this dialectics at a standstill. Mere managerial principles of compulsory attendance in the classes cannot ensure the accountability of the students towards the society. If the attendance policy is geared towards increasing more interpersonal relationships and dialogue among the peers, as some claim ,why is the Dhaba Culture in JNU, which used to be the defining character of the University experience and which had come to become a hub of intellectual discussions, taking its last breaths?

It is too easy to argue about why attendance is not optional in JNU, but a probe into why attendance should be or must be made “compulsory” would reveal certain traces of silences which are, perhaps, more alarming. Every silence has a history of its own and every battle sings of it together!