Today, Indian politics is going through a particular kind of change, especially in the area of politics of uprising. Indian politics has long history of uprising, better to say, India emerged as an independent nation with the Naval Uprising of 1946, a forgotten page of Indian history. Indian democracy has sustained for more than 70 years, with riots and uprising has always been the dialectical but intrinsic part of it. Today, 21st century of Indian politics, our time, is also not separated from it. In fact, the ongoing decades has been witnessing an emergence of new uprisings. The newness can also be measured in terms of intensity of its uprising, for example Lalgarh movement has been unprecedented in its intensity, its breadth, and the challenges it has thrown up in front of the state. Partho Sarathi Ray, Sanhati, January 11, 2010, A Year of Lalgarh , argues “Within a few days of the upsurge in early November, 2008, the entire Lalgarh area was out of bounds for the state, especially its police apparatus, which was the face of the state that had always confronted the adivasis”.

However, here, I am intended to focus only on dalit uprising which has become more frequent, more popular and more visible in India today. I am not trying to propose any normative moral judgment about alit uprising like this is good or bad, nor it is to say to assert or falsify any authentic report about those uprisings, like providing more accurate numbers of death. Instead, I am simply trying to show a hidden potential of contemporary dalit uprisings. These are like- are these uprising a signal of big event? Are these immediate uprising going to set a platform for a historical uprising? Are these dalit uprisings going to give the rebirth of history? (By the rebirth of history, we mean an imminent break of history from where an inexistent people or group of people comes into existent to determine the next journey of history of the society) Or, contrary to it, are these uprisings going to subsume within the liberal representative democracy? Let’s try to measure the truth intensity of contemporary dalit uprisings.

Today, one of biggest challenge Indian state is not facing from the radical armed movement but from the unarmed dalit uprisings. Though, on the one hand, Democratic Ambedkarite leaders are trying to give these forces a democratic direction to change the government in short term and provide a big political platform for Dalit itself in long term. On the other hand, the intensity of uprising and unexpected mass participation in movements is opening a different picture. Let’s start to observe these pictures from the Una Uprising.

Initially, the Una uprising or, rather July 2016 uprising came as an outburst against the atrocities by the Gau-rakshaks, but it soon get converted into the militant refusal by dalit to carry out the so called traditional occupation of skinning and lifting dead animals. This meant, Saroj Giri in an Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) article “From ‘Uprising’ to ‘Movement’: Dalit Resistence in Gujrat”, August 19, 2017, argues, “the focus of the Una uprising was not really on the material basis of caste or on demanding land, but on exposing the casteist basis of society as a whole”.

What we need to understand is that the caste-problem is not only limited to its material aspects, instead society as a whole is casteist. That is why to get rid of caste-problem or radically end caste we must need to refuse the socially assumed work, morality and practices. Perhaps, the uneducated, poor dalits have understood this. The militant refusal had already started in Una uprising. But, with the transition from uprising to movement or, from Una Atyachar Ladat Samiti (militant-sounding) to Rashtriya dalit Adhikar Manch, the populist radicalism with the demand for land came into the picture, that does not fully carry the call of the Una uprising. This transition might be interpreted as a successfully providing the alternatives within the democratic politics for the dalit by supplying a new leader like Jignesh Mevani. But, at the real social level, the social body as a whole that was denaturalised (challenged) during the uprising, with his path of populist radicalism, would re-naturalise the casteist social edifice and overlook the social antagonism of caste.

Again, this would be too fast to conclude Una as a failed uprising, even when this refusal could not generalise itself into a kind of ‘general strike’ against socially assumed work, morality and practices. The rage and intensity of the Una uprising has taken a shape of memory. Badiou in his book The Rebirth of History argues “an immediate uprising”, like Una, “spreads not by displacement, but by imitation. And, this imitation occurs in sites that are similar, even largely identical, to the initial focal point”. But, once again, it is a limited extension. Its potentiality will get decided on the undecided future uprisings and movements.

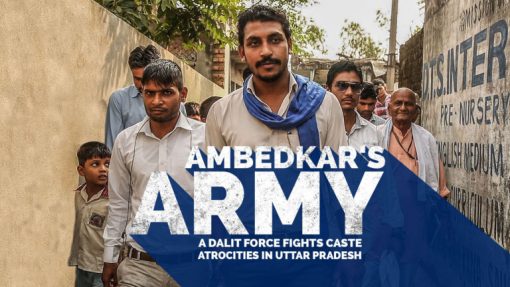

Meanwhile, the Bhim Army, or the Bhim Army Bharat Ekta Mission, an unregistered organisation started by lawyer Chandrashekhar Azad and Vinay Ratan Singh, originated in western Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur district, whose first meeting was held on July 21, 2015, when Azad and Singh decided to start free-of-cost Paathshalas (schools) for children from the community, seems like a revolutionary organisation which has fidelity to the event- the rebirth of history. Whether the historical event- the rebirth of history– will come or not is a question of future but the last year, May 2017, Saharanpur dalit uprising against caste atrocities by the local Thakurs can be credited to the extraordinary active involvement of the Bhim Army for strengthening and organising the voice of Jatavs. Though, there is one critical point to be noted here that the conflicts in Saharanpur goes back to the controversial signboard that reads: The Great Chamar, Village Gharkoli, Welcomes You. It is said that the controversial signboard is the one which first brought the Bhim Army to Gharkoli village in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh. These particularities of uprisings need to be taken seriously to understand the truth intensity of dalit uprisings- like how this idea of ‘Great Chamar’ emerged?

Similarly, the year 2018 starts with the Bhima-Koregaon clashes. On January 1, dalit gathered at the Bhima Koregaon memorial for commemorating a historic battle fought against the British East India Company, in which 22 Mahar soldiers had died. However, Anand Teltumbde in The Wire, January 2, 2018, “The Myth of Bhima Koregaon Reinforces the Identities It Seeks to Transcend”, questions the dalit narrative of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon as the battle of Mahar soldiers against their caste oppression in Peshwa rule. He argues, “When Babasaheb Ambedkar painted the Battle of Bhima Koregaon as the battle of Mahar soldiers against their caste oppression in Peshwa rule, he was creating a pure myth. As myths are required to build movements, he perhaps saw its necessity then. But after a century, when it solidifies into a quasi-history and tends to push Dalits deeper into an identitarian marshland, it should become a worrisome matter”. But, what is important from the purposes of understanding the truth intensity of uprising that even if history of January 1, 1818 is a myth but the January 1, 2018 is on the way to create its own history or not? The Dalit narratives of the battle might be a myth but the January 2018 Bhima Koregoan clashes is a truth. Is this truth- the Bhima Koregoan clashes- going to create a process called truth-process, where yet Inexistent dalit in social and political domain may emerge as existent, or not? (Making inexistent existent is a truth-process in itself, as the inexistent was never non-existent, only their appearance was not realised yet).

Apart from these, we can also see the 2nd April Bharat Bandh, which was called against the dilution of the Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. It is said that the Bharat Bandh was a historical event. For the first time ever, a bandh was organised across the country without being backed by either a national political party or group of parties or by any national organisations. The unexpected numbers of mass participations and the violent demonstrations in few places can not be understood within the electoral politics. This is certainly more but how and how much is the point for future. The more we try to see these dots of uprising into connection to each other, the better its pictures get clarified. The rage and intensity from one uprising may not extend continuously to the general strike today, but its discontinuous imitation/repetition itself sets a background of historical event. This hidden potential of dalit uprisings can be a threat to the current establishment and, a hope of radically challenging the casteist basis of society as a whole.