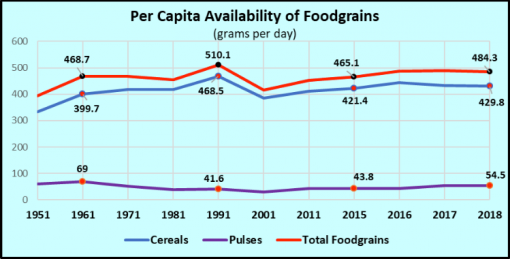

On this 72nd Independence Day of our India, while there will be the usual speeches and festivities, spare a thought to this shocking bit of news: average availability of food grains for every Indian has increased by 3.3% since 1961. Food grains includes wheat, rice, other cereals and pulses. Among these, per person availability of pulses has actually declined by about 10% since 1961.

This should be a sobering thought for everybody whether in the cut-throat world of politics or not. It raises uncomfortable questions of what the priorities of India’s development path are, whether successive govts. have been up to the task of freeing the country from want and hunger and should true nationalism or patriotism not be concerned with this rather than symbolism.

Let us dwell for a moment on these numbers, derived from annual Economic Surveys of the govt. and a recent release by the agriculture ministry. Availability does not mean consumption. It means the total amount available after taking into account damage or wastage, use as seeds, exports and imports. Consumption may be even less.

Also, this is an average. It hides, like all averages, the differences between what a rich family will be getting and what a poor one will get. This difference will be quite significant. The poor, which run into millions even by the govt.’s ridiculously low poverty line, get to consume these life-giving food grains much less than the rich. Average nutritional intake among the poorest 5% of the population was just 1633 Kcal in rural areas and 1637 Kcal in urban areas, revealed an NSSO report for 2011-12, the last of its kind. The richest 5% of the population consumes 2233 Kcal in rural areas and 2206 Kcal in urban areas on an average.

As the chart above shows, the highest availability level of 510 grams per day (gpd) was reached in 1991. Since then, it has come down to 484 gpd, a dip of about 5%. Since 1961, availability of pulses – one of the key sources of proteins for Indians – has declined from 69 gpd to 54.5 gpd.

It is true that while looking at nutritional intake of Indians, other food items too need to be considered, like eggs and milk, availability of both of which has increased significantly since Independence. But surveys indicate that this replacement of foodgrains by say, milk or eggs, is highly exaggerated by both govt. propaganda and public perception. Contributions of these items to nutritional intake are not increasing much over the past three decades, despite enormous increase in production.

For instance, the NSSO Survey report mentioned earlier reveals that contribution of milk and milk products to protein intake was 8.8% in 1993-94 which inched up to 10% in 2011-12, in rural areas while in urban areas it increased from 11.66% to 12%. For eggs, meat and fish (taken together as a category), the contribution was just 3.66% in 1993-94 and increased to 7% in 2011-12 in rural areas while in urban areas it increased from 5.29% to 9%.

So why this paradox of increasing production and hence, increasing availability, yet not much change in nutritional intake? This is happening because of the endemic inability of the vast majority of population to buy certain kinds of food – like milk and eggs, etc. In other words, it is persistent poverty.

The skew in consumption of milk and eggs etc. between the rich and poor is much more marked than for cereals. The NSSO survey found that among the poorest 10% of population just 3% of the protein intake comes from milk and another 3% from eggs, meat and fish, in rural areas. At the other end, among the richest 10% of population, 15% of their protein is coming from milk and another 9% from eggs, etc. In urban areas the differences are even more marked.

For the vast majority of population, food grains are still the main source of nutrition. And, average availability has remained the same for decades. In fact, the imposition of Aadhaar linking of ration cards has become another source of deprivation leading to at least 15 starvation deaths.

In sum, 71 years after the tryst with destiny, India still grapples with the biggest slavery of all – hunger. None of the policies and the slogans – whether ‘garibi hatao’ or ‘sabka vikas’ – have made much of a dent. And, the new slogans of ultra-nationalism too seem to be unconcerned about the people. They are more worried about the flag and the anthem and the cows. Indians still await their destiny.