Individuals do matter in politics. Some may represent the spirit of their times, with all its contradictions and weaknesses. Others appear at the right moment to lead the way out of what seems to be a state of disarray or chaos. Yet, others lead the way to the future, seizing on opportunities that others would have passed by. On a lower scale, they may be responsible for and/or may be representative of more modest changes and shifts. But, they do matter and the question of like and dislike, love and hate must take second place to a more objective and substantive assessment of their role.

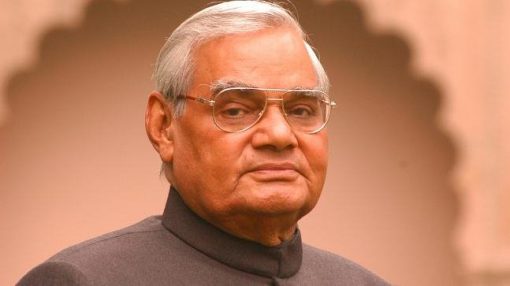

Atal Bihari Vajpayee's ascent to prime ministership, once in a brief stint that was never going to survive a vote of confidence, and later in two substantive ones, marked the final phase of a significant right-ward shift in India's society, economy and polity that had begun in the Narasimha Rao regime. What the earlier one lacked and the Vajpayee dispensation provided was a sharp right-wing turn in foreign policy. The shift away from the earlier public sector-dominated and tightly regulated regime to a new reform mantra and opening up of the economy, as well as the undermining of the goal, if not the practice, of secularism, had already taken place in the earlier period. But the turn in foreign policy was inaugurated by the Pokhran explosions, and underlined by the letter to Clinton explaining the reasons why the tests had been undertaken – the triumphalism of the first set off only by the abjectness in private of the second.

Vajpayee and his Cabinet – including Advani, Jaswant Singh and Murli Manohar Joshi, to name some of the most prominent among its figures – lent political credibility and muscle to a trend in the making for some time in private amongst the bureaucracy and some political circles. Figures like Brajesh Mishra, J. N. Dixit, K. Subrahmanyam, K. R. Narayanan, joined by lapsed Congressmen like K. C. Pant, and pro-nuclear scientists like R. Chidambaram and Abdul Kalam, perhaps even Congress leaders like Pranab Mukherjee and earlier R. Venkataraman, had long been for overt nuclearisation, even while serving Congress governments. If the abandoning of non-alignment and the strategic shift towards the US was not so clearly expressed, it was a logical consequence that would be welcome to those who were very much with the shift in economic policy. The political contribution of the BJP was to yoke the "victimhood" that important sections of the Indian elite were constructing with respect to India and the global nuclear regime, to the potent communal weapon of the "victimhood" of the Hindu majority that the BJP and the Parivar was so assiduously nurturing in the domestic arena. Pakistan was the glue that cemented these two strands of victimhood together, with China, the "perfidious" neighbour and Pakistan's ally, as another binding factor.

There can be no doubt that Vajpayee, together with his trusted advisor Brajesh Mishra, was among the key architects of this line, among its most powerful articulators and implementer-in-chief. If Vajpayee's demeanor and image at times belied this reality, one should recall the frequency with which his foremost colleagues were equally shown up to be ham-handed and bungling on several occasions. Advani's strategic threats to Pakistan following the tests were shown up to be the bombast they were by Pakistan's own nuclear tests shortly after. The climb-down in rhetoric that the Kandahar standoff forced on Vajpayee and his team need not be forgotten. While Murli Manohar Joshi pursued the astrology-in-universities agenda, Arun Shourie presided over the chaos of disinvestment of the PSUs. Collectively, their nuclear hubris led India to Kargil, a war that could have become a disaster. But, their political formula succeeded in delivering electoral success following Kargil, a striking illustration not as much of the cleverness of the Parivar, as of the political backwardness and lack of awareness of Indian voters, who returned Vajpayee to prime ministership once again.

Having launched the strategic right-ward turn, the Vajpayee government could not deliver on its successful culmination. The attempts of Jaswant Singh to placate the US, chasing his counterpart Strobe Talbott across the globe for meetings, from airport to airport, were a nadir in the exercise of India's foreign policy. It was left to Manmohan Singh to consolidate it with the nuclear deal – as the latter himself told Vajpayee, "I have completed what you had begun." But, sophistication and nuance aside, the strategic viewpoint of the BJP (however ham-handedly expressed) and the nuclear ambitions of a large section of the Indian elite came together at a critical juncture, to execute a major shift in India's foreign policy.

The Vajpayee ministry presided too over a spate of communal killings, from the brutal tragedy of Graham Staines and his children to the pogrom of Gujarat. Even a child can see beyond the simplistic construction of a "poetic, sensitive" Vajpayee to the reality of a master political figure who gave voice and muscle to Hindutva at its first taste of Central authority. Only a less than critical media can confuse personal affability with political and human sensitivity. Narendra Modi has clearly gone beyond the Vajpayee legacy. His is a more forthright, self-confident image – both of himself as a person and of his government. No quarter is given in the war of image and propaganda. In foreign policy, Modi may even be termed hyperactive – though without much to show concretely. Unluckily for him, the world is busy with bigger actors and more significant events, and attention is not focused on India, or South Asia, in the way it was during the Vajpayee regime. In the domestic arena, Modi has gone far beyond what his erstwhile leaders and mentors achieved – the continued right-ward shift of the elite, the poor record of Congress rule and the developed political acumen of the Parivar (and its significantly increased recourse to violence, especially of the non-state variety), all having contributed to that development.

Vajpayee was no liberal or Nehruvian, as some commentators would have us believe today. But, while he was among the foremost of the leaders who laid the foundations for what the Parivar is today under Modi, he will also be counted with Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh as one of the architects of the India of the first decades of the new millennium. Not an India that is an advance over the earlier vision, but an India fast slipping to the world's most significant reservoir of the poorest and most deprived, driven by majoritarian and nationalist hubris, squandering even the limited gains of an earlier era.