The killing of John Allen Chau, a 26-year old American adventurer and self-proclaimed Christian proselytiser, by determinedly isolationalist Sentinelese aboriginals in the Andaman Islands archipelago a few days ago, has cast fresh light on India’s changing and flawed policy towards the vulnerable hunter-gatherer communities of the Andamans.

The young man, definitely foolhardy and perhaps even delusional, had taken upon himself the condescending task of bringing enlightenment to the Sentinelese, who he had described in his web journal as the “last haven of Satan.” He had bribed a local guide and several fishermen to illegally ferry him to the forbidden North Sentinel island, had been injured by arrows shot by irate aboriginals in his first foray, and had made a return journey alone, only to be predictably killed by a flurry of arrows. The Sentinelese buried him in the beach sand and, at the time of writing, were being watched by police from a safe distance to determine if, and how, they could try to retrieve the American’s body.

The Andaman police have arrested the seven collaborators who had violated the legal provision prohibiting any approach within 3km of the North Sentinel island and any contact with the tribe. One would laugh, if it were not so tragic, at press reports that the authorities were also wondering if they should or could prosecute the Sentinelese involved in the killing!

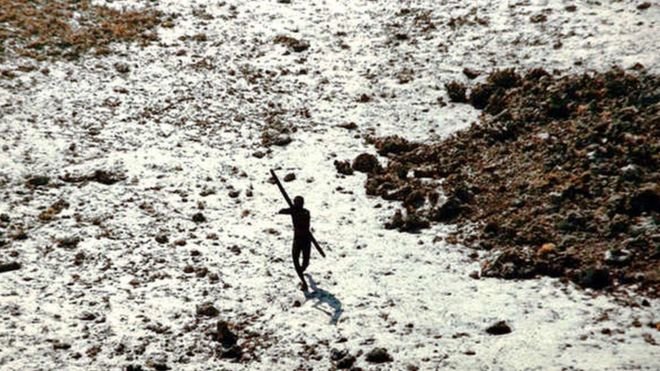

The simple facts are that there are clear Indian laws against what the young American did, that the official Indian position is not to intrude into the territory and lives of the Andaman aboriginals, particularly vis-à-vis the most endangered tribes such as the Sentinelese in their islands and most Jarawas in their reserve forests. The former are believed to number only around 100 or so, or even lower according to some estimates, while the latter may be as many as 400.

The Sentinelese have fiercely resisted any contacts, including shooting arrows at helicopters sent to verify their status after the 2004 tsumani, and a few years later killing two local fishermen who were fishing close to their island and, later tying their bodies to stakes on the beach to warn other intruders.

For long, the Indian government had followed what must be seen as a wise and enlightened policy of leaving these communities to themselves, especially given its attitude towards particularly vulnerable tribes (PVT) and other adivasi peoples in mainland India where the State has rarely shied away from intrusive “development” in their areas even against their express wishes.

The former colonial British administrators too, in the face of the Andaman aboriginals’ persistent hostility towards contact with outsiders, and the low percentage of intervention in the few inhabited islands of the archipelago where these tribes lived, had abjured efforts to interact with these communities.

Under the advice of sage anthropologists and administrators, India, too, broadly followed this policy, especially mindful of the potentially disastrous consequences outside contact could bring to these isolated communities, which had no immunity to diseases such as influenza. Even as late as the 1990s and early 2000s, measles and malaria took many Jarawa tribespeople and threatened the rest. Thus, only occasional and consensual efforts were made to make physical contact with these communities, at least to check on continued welfare, enumerate the steadily dwindling population of these tribes and, where possible, study their languages and customs.

This broad policy outlook of “eyes on, hands off” has been followed till recently, in most cases quite strictly, particularly vis-à-vis the most endangered tribes. However, the policy was breached in the 1990s by construction of the Grant Andaman Trunk Road (ATR) from Port Blair, the administrative capital of the Union Territory of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, to the Baratang jetty point in the north of the Middle Island, running right through the heart of the Jarawa territory. Many Jarawas were killed, several by electrified fences, during the roadway construction, and many workers too were killed by the Jarawas. Most Jarawas retreated into the depths of the reserve forest, and gradually accepted the barest of interactions with outsiders, notably after a tribal youth had fractured his leg falling off a tree and was successfully treated at a local hospital.

Today, a few fringe tribespeople can be seen at key halts, clothed and sometimes even interacting with locals and tourists, taking away caps and sunglasses, with tourists under instructions not to react. Many tourist buses have come to be operated along the ATR primarily for “tribal tourism” despite being banned, often with official and police collusion. A Supreme Court order in 2013 banned tourists from traveling down the ATR in the wake of videos telecast abroad showing police coercing naked Jarawa girls to dance for tourists. A ferry service now runs from Port Blair to the Baratang jetty, but “tribal tourism” is known to continue along the ATR and flourish in many other forms.

As late as this year, the Andaman administration exempted foreign tourists from requiring a Restricted Area Permit to visit 29 islands in the A&N archipelago including nine islands with PVT communities. Tourism to the islands is being encouraged in a big way, much against saner advice by anthropologists and other experts. Hotels are coming up with little concern for the local ecology. Polluting motorboats and yachts ply to many hitherto pristine islands, spreading pollution and waste in their wake. Many such vessels are known to ply close to islands inhabited by PVT groups, even though the Coast Guard undertakes frequent patrols.

The Andaman Islands cannot withstand this ecological and cultural onslaught. The severely endangered and rapidly dwindling aboriginal groups in these islands have even less capacity to resist or escape life-threatening harm which has already rendered many tribes extinct. India should be really proud that it has such rare, pre-Neolithic “uncontacted” tribes, of which there are not more than around 200 all over the world and that, by and large, it has so far taken many commendable steps to protect them from the unwanted ravages of outsiders. In the aftermath of the unfortunate death of John Allen Chau, will the Indian government now wake up and change its present policy that can only end in disaster?