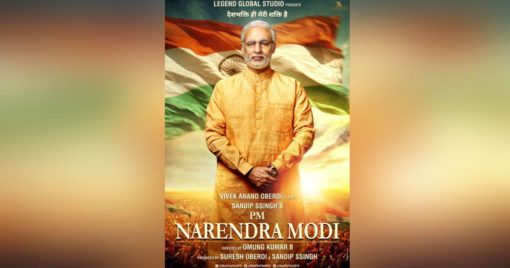

Even as the Election Commission of India submits a detailed report to the Supreme Court regarding the alleged violation of the Model Code of Conduct by the release of highly controversial biopic PM Narendra Modi, various questions have been raised about the role of films as propaganda. Recently the relationship between politics and cinema has become even more pronounced than it was before. Examples include Uri: The Surgical Strike, which dramatises a military mission conducted against Pakistan in 2016, and The Accidental Prime Minister, an unflattering portrait of former prime minister Manmohan Singh.

The release of a biopic on Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems like a sequel to these movies which have propagated the ideology of the current establishment in the run up to a crucial general election. Watching these films reinforces a notion of the superiority of the establishment, at the expense of factual accuracy and sensitivity. In the vacuum of an unfree press, these films led many people to draw erroneous conclusions regarding the government and its policies as well as about the personalities of opposition leaders.

The biopic paints Modi as an efficient administrator and flatters him as the greatest Prime Minister of India. The agenda is to bolster Modi’s persona and is designed to provoke devotion rather than reflection or debate. It fictionalises Modi as hardline patriot, as it were, and sets the stage for his advertisement as the most desirable PM.

It also tends to whitewash Modi’s role in the 2002 Gujarat carnage. As Salil Tripathi has argued about the corporate media’s attempts to show Modi as an inclusive statesman, “the strategy to remake Modi begins with the claim that the Modi of 2014 is not the Modi of 2002; that he appears to have moderated his views”.

Given the ways that the cinema apparatus transcodes social discourses and reproduces ideological effects, it is important to understand that the “film ideology” is transmitted through images, scenes, generic codes, and narratives. As the hegemony of right-wing forces gains ground in many institutions, the system of knowledge and information dissemination too has come to be subjugated under this brute control. The ideologically biased nature of film censorship shows an attempt to buttress a certain kind of cultural knowledge, and excise another, leading to the creation of a precritical and misinformed citizenry.

A History of Contradictions

For much of history, the connection between politics and film has been both intimate and concealed. Films have often served as a tool of propaganda given their ability to reproduce images, movement and sound in a manner that seems extremely lifelike to us. In our times films possess a unique sense of immediacy capable of creating the illusion of reality. For these reasons, movies are often taken to be accurate depictions of real life. This issue becomes even more pronounced when films depict unknown cultures or places.

While being a source of entertainment, movies are able to mould social consciousness by distorting historical events. It is a wonder we don’t consider films a more untrustworthy medium. Political officials have long been aware of cinema’s powerful attributes, and have used the medium to mobilise and indoctrinate society with different views.

To take US films from the 70s, even the most socially critical films (such as the Jane Fonda films, or Network and other films by Sidney Lumet) posited individual solutions to social problems, thus reinforcing the conservative appeal to individualism and an attack on statism or collectives such as unions. The film Rambo would show returning Vietnam War veterans transforming themselves from wounded and confused misfits into super warriors. All of these post-Vietnam syndromes, pre-Reaganite films show the U.S. and the American warrior hero victorious this time round. They also provide symbolic compensation for loss, shame, and guilt by depicting the U.S. as good, while its communist enemies are represented as the incarnation of evil receiving a well-deserved defeat.

The Controlling Mirage of Objectivity

It is an error to see films or videos as a vehicle of simple information. Even the creation of documentary films resembles the writing of history. Each process entails the creation and presentation of “facts”. It is amenable to falsification or modification. So, it is essential that moviegoers create a critical eye of their own, while viewing films. As a tool of propaganda, cinema can either create divides or bridge them. By becoming and remaining critical and rational viewers, able to see art for what it is, perhaps we can keep ourselves from falling for the trap.