Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

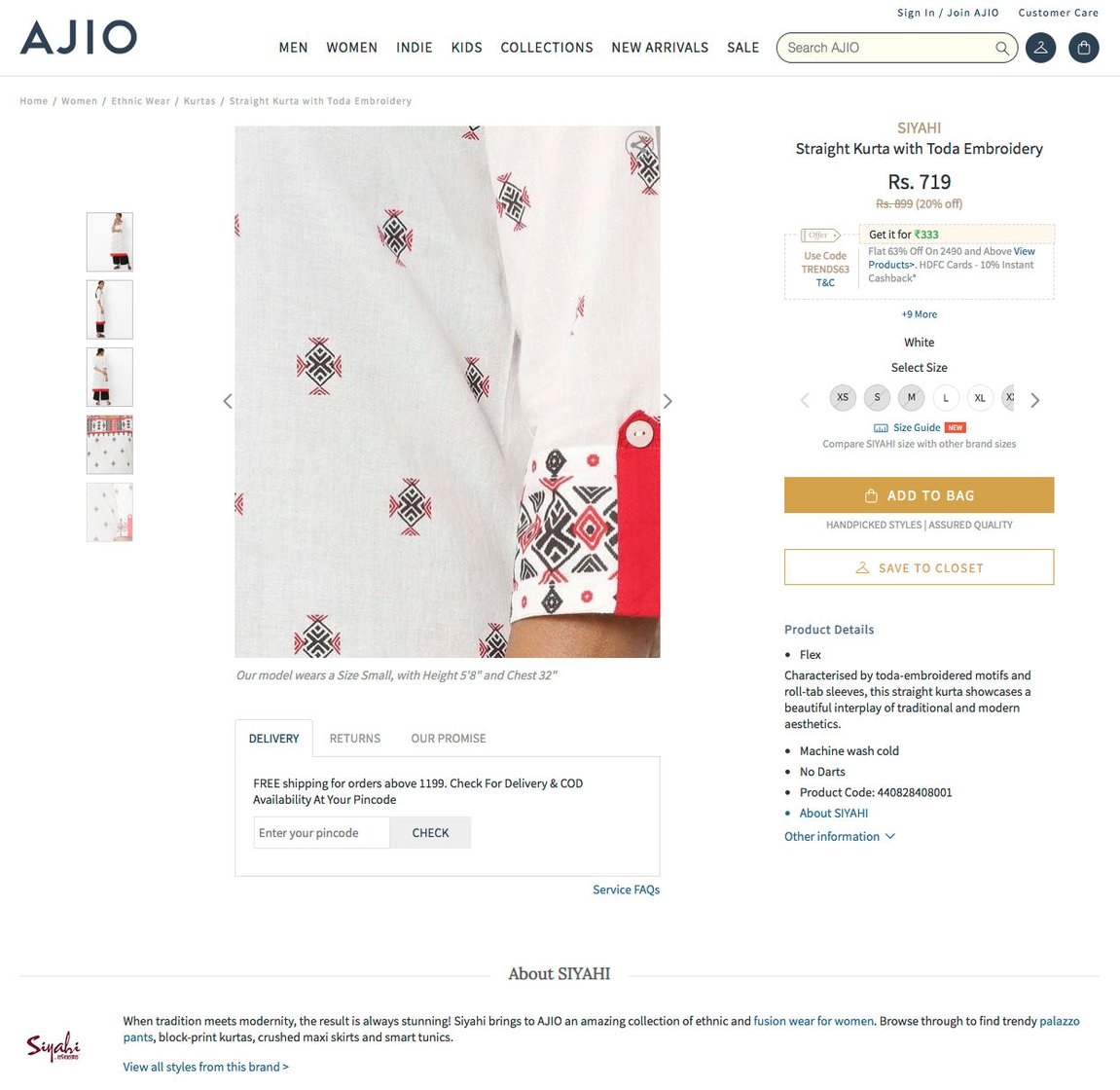

“See this photo of a tag on a kurta [marketed by a big brand] talking about ‘Toda embroidery’. It is a print stamped on the cloth! And they have not even bothered to get the facts right, calling the embroidery ‘pukhoor’ and other words that don’t even exist in our language,” says Vasamalli K.

In the Toda language, the community’s embroidery is called pohor. Vasamalli, in her 60s, is a veteran embroider who lives in Karikadmund hamlet in Kundah taluk of the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu. Around 16 kilometres away, in Ooty (Udhagamandalam) town, Sheela Powell, who runs a Toda embroidery products outlet, was incredulous too when she saw a ‘Toda’ saree being sold online for just Rs. 2,500 by another well-known retailer. She immediately ordered it. “It was advertised as a ‘Toda embroidered saree, skilfully hand embroidered by the women of Tamil Nadu’. I wanted to know how they could price it so low and where it was done.”

The saree was delivered in a few days. “I saw it was machine embroidered, and the reverse was covered with a strip of cloth to hide the untidy threads,” Sheela says. “Yes, the embroidery was in black and red, but that was the only similarity.”

Traditional embroidery, done by women in the Toda community, has distinctive red and black (and occasionally blue) thread work in geometric designs on unbleached white cotton fabric. The traditional Toda dress is a distinctive shawl, the putukuli. Considered a grand garment, it is only worn for special occasions like visits to the temple, festivals and finally as a shroud. Around the 1940s, Toda women began to do made-to-order piece work for British buyers – tablecloths, bags and other items. For the next many decades, sale was limited to those who requisitioned the items. Only cotton thread was used in the past, though now most Toda women use wool thread, because, they say, it is less expensive and faster to work with.

Old style Toda embroidery using cotton thread. Toda artisans say they take their inspiration from nature, and the colours symbolise the different stage of human life. Bottom right: T. Aradkuttan and U. Devikili wearing putukulis (traditional shawls embroidered only by Toda women) in Bhikapatimand hamlet of Ooty taluk | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Old style Toda embroidery using cotton thread. Toda artisans say they take their inspiration from nature, and the colours symbolise the different stage of human life. Bottom right: T. Aradkuttan and U. Devikili wearing putukulis (traditional shawls embroidered only by Toda women) in Bhikapatimand hamlet of Ooty taluk | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

“Even so, it’s very intricate [work] and strains the eye, so one can only work for three to four hours a day,” says Simmavani P., 54, Vasamalli’s sister-in-law. There are no traced designs, and the warp and weft of the fabric are used as a grid to embroider. Some stitches are tightly held, others have loops of thread hanging as part of the design. There is no reverse in a Toda embroidered piece, so neat is the work on both sides – a matter of great pride among the artisans.

“A six-metre saree takes at least six weeks to embroider and will sell for at least Rs. 7,000 rupees. It is not economically possible to sell a genuine piece for Rs. 2,500-3,000,” explains Sheela.

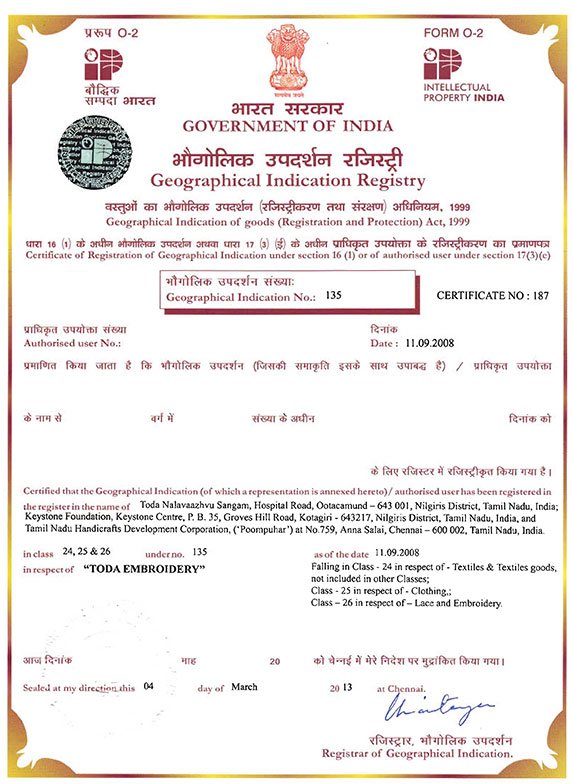

Not only are the descriptions by the big brands misleading, they could also be an infringement. Toda embroidery received a GI (geographical indication) certificate in 2013. A GI is given by the government to protect the traditional knowledge of a community or producers of particular foods, trades and craft. It’s like an intellectual property right, or a patent. The GI status for Toda embroidery means anything created outside the Nilgiris district is an infringement, as is any method of production not done by hand. The Toda embroidery GI is jointly owned by Pompuhar (the Tamil Nadu Handicrafts Development Corporation), Keystone Foundation (an NGO working in the Nilgiris) and the Toda Nalavaazhvu Sangam (a body of some Toda artisans and a non-Toda dentist based in Coonoor).

Despite the GI, says Vasamalli, “big companies outside the Nilgiris are copying our embroidery using machines or as a print and calling it ‘Toda embroidery’. How can they do this?”

Simmavani P. says Toda embroidery has switched from cotton thread to wool, which is cheaper and easier to work with. | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Simmavani P. says Toda embroidery has switched from cotton thread to wool, which is cheaper and easier to work with. | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Sheela Powell, who runs a Toda embroidery products outlet, was incredulous when she saw a ‘Toda’ saree being sold online for just Rs. 2,500 by a well-known retailer | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Sheela Powell, who runs a Toda embroidery products outlet, was incredulous when she saw a ‘Toda’ saree being sold online for just Rs. 2,500 by a well-known retailer | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

It’s not just big companies, other craftspeople are also infringing. At a handicraft exhibition in Jaipur, Vasamalli found Toda designs on woollen shawls in another stall. “One customer came to fight with me saying why are your items so expensive when they are selling the same thing for the half the price?” she says. “It [the other stall’s item] was not hand embroidered, but a stamped pattern and [so] it was much cheaper."

There is also a fear within the community of non-Todas acquiring the embroidery skills because the Toda population is small – just 2002 people in 538 households across an estimated 125 Toda hamlets in the Nilgiris (Census 2011). By their own estimates, there are around 300 women in their community who practice pohor. However, the interest among younger women is dwindling, which puts the future of the craft at risk.

In Nedimund, a Toda hamlet in Coonoor taluk, 23-year-old artisan N. Sathyasin’s predicament speaks for others like her: “The work is a lot and it takes a lot of time. As labourer in a [tea] estate I can get 300 rupees or more a day. For this work I spend two to six hours a day and get only about 2,000 rupees at the end of the month.”

Sathyasin works with Shalom, the Toda products outlet run by Sheela (who is not from the Toda community). Shalom too has been criticised by some Todas for employing non-Toda women. “They do the ancillary work such as stitching, attaching beads and tassels, but not embroidery,” Sheela counters. “I am aware that the craft will lose some of its value if just anyone takes it up. Right now it is precious because it is so little, only so many pieces a year and each piece is unique. But it’s a big challenge to get this work done and to keep it going.”

N. Sathyasin’s predicament speaks for other young Toda women too. | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

N. Sathyasin’s predicament speaks for other young Toda women too. | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Vasamalli K. says, 'Big companies outside the Nilgiris are copying our embroidery using machines or as a print and calling it ‘Toda embroidery’. How can they do this?' | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Vasamalli K. says, 'Big companies outside the Nilgiris are copying our embroidery using machines or as a print and calling it ‘Toda embroidery’. How can they do this?' | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

The outlet was started in 2005 and has 220 Toda women on the rolls embroidering pieces which get converted to products like sarees, shawls, bags and linen. Of each saree sold for Rs. 7,000, around Rs. 5,000 goes to the artisan, and the remaining is used for the material and marketing, Sheela says. Most of the experienced artisans earn, on average, between Rs. 4,000 and Rs. 16,000 a month, depending on the amount of work they take on. Shalom posted a turnover of Rs. 35 lakhs in 2017-2018 and many in the Nilgiris credit it with helping the market for these products grow.

Vasamalli shrugs, resigned to the inevitable: “If non-Todas do it will lose its value. But on the other hand if enough people don’t do it, it will die out completely.”

With a high literacy rate of 84 per cent, Todas now have jobs in banks and other services and are considered fairly well-to-do. Vasamalli too has a Masters in Sociology, is a member of the Tamil Nadu Tribal Welfare Board, and a published author with the Sahitya Akademi.

“It is the headache of us Toda females! The men are not bothered who is doing embroidery and who is copying,” she says. “Selling [of our hand embroidery] and doing business is not a traditional thing in our culture, so men are not serious about it. For us women it is both – we have to protect our cultural right and at the same time not incur economic loss.”

The Toda embroidery cause is not helped by the fact that there is no single overarching body of Toda artisans to address these issues. “We are scattered as a community,” Vasamalli says. “There are multiple bodies, it has become very political. I am a member of many organisations, but even I am unable to gather everyone around this. We need help.”

The GI certification for Toda embroidery | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

The GI certification for Toda embroidery | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Big brands are selling fictitious Toda embroidery products | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Big brands are selling fictitious Toda embroidery products | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Big brands are selling fictitious Toda embroidery products | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Big brands are selling fictitious Toda embroidery products | Image courtesy: Priti David/People's Archive of Rural India

Meanwhile, Bengaluru-based lawyer Zaheda Mulla, who specialises in intellectual property rights, patents and copyrights, and was commissioned by Keystone Foundation for the Toda embroidery GI, is in no doubt that there is a legal case. “In Toda embroidery, the ‘method of production’ refers to embroidery done by hand only,” she says. “If this embroidery is done in any other way such as by machine, then it is incorrect to call it ‘Toda embroidery’. In other words, machine embroidered products sold as ‘Toda embroidery’ would amount to infringement. As part of the registration process, certain unique designs are also registered.”

However, she adds, “You need muscle power to implement and propagate awareness among end consumers. GI holders and genuine producers (called ‘authorised users’ in the GI certificate) affected by counterfeit sales must seek legal remedy by filing an infringement suit [in the high court of that jurisdiction].”

The two brands marketing so-called Toda embroidery, that are referred to in this story, are Siyahi of Reliance Trends and Tjori.com. Despite repeated emails seeking clarity on the product and its description as given on the site, Tjori did not respond.

In response to an email sent by this reporter, [email protected] wrote: “Siyahi is a brand that takes inspiration from Traditional Indian crafts. We do not do original products produced by Craftsmen. Embroideries are all machine done. Embroideries are all done on computer embroidery machines in factories. Inspiration has been taken from Toda shawls.”

But Vasumalli is not placated. “Copying our designs and using our name is not correct,” she says.