The report of the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) conducted in 2017-18 is finally out, and it confirms what had been leaked earlier, namely a dramatic increase in the unemployment rate in the Indian economy. The unemployment rate is given under two heads: usual status unemployment and current weekly status unemployment. These can be understood as follows.

If a person is employed or seeking work for more than half the time (“majority time”) during the preceding 365 days before the date of the survey then his or her “usual status” is that he belongs to the labour force; but if the person does not succeed in getting work for more than half the time then he or she is considered “usual status unemployed”.

A further modification is made to this to make it less restrictive. All individuals who are outside of the labour force according to the above definition, or are unemployed, but have worked for not less than 30 days during the reference year are classified as “subsidiary status” workers. The total labour force then is defined as “Usual Status (Principal Status plus Subsidiary Status)” workers. Likewise, all unemployed according to the above criterion who have worked for not less than 30 days are considered to have been employed in a “subsidiary status” activity. The Usual Status (PS+SS) unemployment rate, therefore is less than the simple “Usual Status” unemployment rate for two reasons: first, the denominator, labour force, is higher because of the inclusion of persons who may have worked in a subsidiary activity; and second, the numerator, unemployment, is lower because of the inclusion of persons who may have worked in subsidiary activities.

Finally, if a person is working, or available for work, even for just one hour during the week preceding the survey, then that person belongs to the Current Weekly Status (CWS) labour force. But if that person is unable to obtain even one hour of work during the entire week, then he or she is considered unemployed on the CWS basis. These are the concepts of unemployment which the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) uses and on which the PLFS provides data for 2017-18. Let us see what the data show.

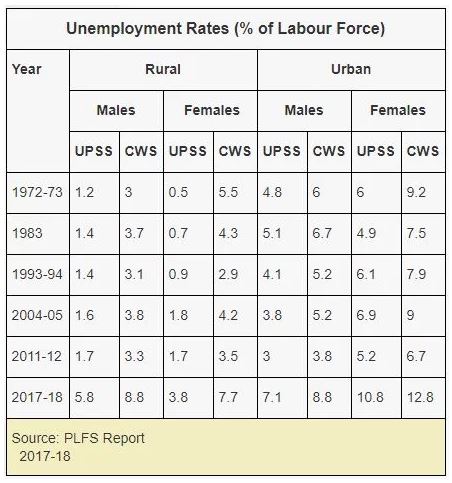

Because the Usual Status (PS+SS) unemployment rate refers to long term or chronic unemployment, which is somewhat lower in India (underemployment being more common here), it has been quite small in the past. In 2011-12, for instance, it was merely 2.2%. In 2017-18, however it went up to 6.1%;and this increase was across-the-board, for males as well as females, and for rural as well as urban India. What is more, exactly the same is true of the CWS unemployment rate: this too has gone up across-the-board compared to the earlier NSSO rounds. The following Table gives the picture.

A sudden jump in the unemployment rates across-the-board in 2017-18, compared to all preceding rounds of the NSSO, is unmistakable. There has been an attempt by the government to fudge the issue by claiming that because of the changed method of estimation, the 2017-18 figures are not comparable to the figures thrown up by the earlier rounds of the NSSO. This, however, is completely wrong. The change in methodology refers to other issues, such as the division of the population by educational levels, on which data have been collected and presented. It has no effect on the overall figure. As a previous Chief Statistician of the country, Dr. Pronab Sen, has clarified in an interview, the 2017-18 figures for the overall unemployment rates are perfectly comparable with the figures of the earlier rounds. This is the comparison presented above.

In fact the unemployment situation in 2017-18 is much worse than what even the above Table brings out. This is because there has been a drastic fall in the work-force-to-population ratio among rural females between 2011-12 and 2017-18. This ratio has been low for quite some time, an obvious reason being the “discouraged worker” effect: in a situation of high unemployment, women tend to withdraw from the work-force because of slim prospects of finding a job. But it has intensified in the last few years, especially during the NDA rule. Had the women’s participation rate been as high as before, the unemployment rate in 2017-18 would clearly have been much larger. This therefore begs the question: what has happened in 2017-18 and the years leading up to it that has suddenly given rise to such an acute unemployment situation?

An obvious proximate factor is the twin-damage inflicted upon the economy by the Narendra Modi government, in the form of demonetisation and the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Since demonetisation was introduced in November 2016, its impact must have been felt precisely during the survey year 2017-18. Likewise, the GST was introduced on July 1, 2017, and its impact must have been felt in the survey year. Both these measures dealt a severe blow to the petty production sector of the Indian economy which is a major employer of the nation’s work-force. And this, naturally, has made itself felt in the 2017-18 PLFS. There are innumerable micro-level studies of the adverse impact of demonetisation and GST on employment in particular sectors. The PLFS survey simply reflects this situation.

It would be wrong, however, to think of the grim employment scenario as being the product of just two blunders by the Modi government. For a long time, the annual addition to the labour force has been much less than the jobs created in the economy. Estimates made by various researchers suggest that 10-12 million additional jobs have to be created every year in order to absorb the addition to the work-force without even making a dent on the backlog of unemployment that already exists; this is the other side of the so-called “demographic dividend”. The actual additional job creation by contrast has only been a fraction of this figure. A worsening of the unemployment situation under these circumstances is inevitable.

In fact, one can argue that the figures of unemployment given above, the UPSS and the CWS, do not at all capture the actual unemployment problem. This is because there is a tendency over time for jobs to get shared among people. Suppose for instance a person was getting 10 hours of work per week. Then by the CWS he would be considered employed. But suppose because of the vast numbers of new entrants to the job market, the number of hours of work that the person gets is reduced to say 5 hours. Even then, by the definition of CWS unemployment, he would still be considered employed. Work-sharing in other words, which is typically the form that unemployment takes in the Indian economy, does not get captured by the above unemployment measures. And one can think of situations where the unemployment rate by these measures does not go up even when the employment situation is becoming worse.

Worsening unemployment through work-sharing would get captured if we have a concept of “income unemployment”, where a person would be considered unemployed if he or she gets an income per month which is less than a certain “benchmark” level that defines employment. Income unemployment has been rising in the Indian economy quite steadily.

This can be seen very simply. Suppose income unemployment was not rising. This would generally mean that more and more persons would be getting an income above the benchmark figure. Since the income elasticity of demand for foodgrains is positive, this should have meant a larger demand for foodgrains in the economy, and hence, in a situation where per capita foodgrain output has not been rising, an inflationary situation in the foodgrain market and in the economy as a whole. This has not happened; on the contrary, foodgrain inflation has remained remarkably subdued despite the fact that per capita output and availability has not increased at all if we compare 1991, when economic liberalisation was introduced, with today. The reason is that an income compression has been inflicted on the people, to which growing unemployment has been a contributory factor.