Showing the interiors of his hut, Dablu Mallik says: “Our grandfather came here from Parsauna village 50 years ago. This is my maternal property. I couldn’t erect a brick here; I am poor. Even this bamboo hut costs Rs 20,000.”

He says his father is mentally ill and he doesn’t have money for his treatment. “Whenever we go to the government hospital, they hook up an intravenous drip…as it finishes, we are asked to leave,” he says, worriedly, adding that “I am illiterate but not an idiot. How can a mental illness be treated with a drip?”

Manual scavenging is the only source of income for Dablu to support a family of six. Like Dablu, there are more than 300 families of Doms and Mehtars in Dom Toli of Bettiah for whom there is no escape from reality except to engage in traditional bamboo weaving and manual scavenging.

“Baans ke kam karin le. uhe se laika ke khiaine. Ab ihe madai tati sahara ba (I weave bamboos. This is the only source of income for me. All left for us is this bamboo hut.),” says Kanti Devi, a widow. “A bamboo,” she says, “costs Rs. 250. I buy one bamboo at a time; I can’t afford more than that.”

Kanti, 35, earns a maximum of Rs 200 a day by weaving bamboos. She sells the products to a middleman at the outpost who then sells them in the town market. She has four kids —two girls and two boys. She married her eldest daughter under 18 years of age a few years ago. She laments, “How can a single parent manage the needs of four children?” Her younger daughter Ruti Kumari studies in class 5 in a nearby government school. Pawan and Prem, her sons, study in Class 5 and Class 3, respectively.

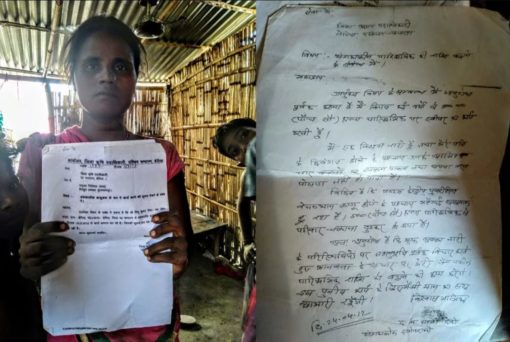

Kanti was a temporary sweeper in the Agriculture Department’s office. “I worked for 15 years but I was not made a permanent employee. They were not even releasing my payment for months,” she continues, “I got multiple applications written to sahibs in the department but none paid attention to my plea. One day I gathered courage to write to the Collector to increase my salary.” As she wrote to the district magistrate, her dues [salaried at Rs.700 per month for a couple of months] were paid but her employment was discontinued for complaining [highlighting the issue outside the department].

The financial condition of Shanti Devi, Kanti’s neighbour, is no different. Shanti works as a sweeper in some upper caste families. “I sometimes hide from families where I work that I am an achhut (untouchable),” Shanti admits. “We doms are called to feast in the funerals of Hindus [upper castes], they say that we are the door to moksha (salvation). But after the feast, we again become untouchables.”

Holding her grandson on her lap, Shanti murmurs,”Ekni ke ka hoyi, kaise padhiyen san ee garibi me. (How they will study in this poverty.)” Her married son is also into traditional bamboo weaving.

Anuradha Devi, who is weaving bena (hand fans) at her home, tells us that 25 benas can be made from a bamboo. She says, “Each bena costs between Rs. 10 and Rs. 20, depending on the demand.” “Many people in the town have proper power backup for electric fans thus the demand of hand fans has fallen.”

The two lanes of Dom Toli are separated by a stagnant sewage line. Ushmi Devi, whose hut faces the sewage line, says, “This overflows when there is rain. We are suffering because we have to. None from the municipality comes to clean the toilet; it is left to us because it is our caste job.” There is only one public toilet in this lane that houses more than 50 Dom families.

Rajwanti Devi, Ushmi’s married daughter lives with her. Rajwanti says, “The family of my husband doesn’t respect me.” She was working as an agricultural labourer in Punjab’s fields some years ago. After the birth of my children, it was quite difficult to manage them alone in a foreign place; that is why I came back.”

Sujit Mallik, 28, is unstacking the bamboo bundle which he bought in Rs 1,800. He expects a profit of Rs. 1000 on this. “Abhi roj ka nali- mori ka kam kar ke aye hain, kal se isme hath lagayenge (I just have returned after finishing the routine scavenging, will start weaving tomorrow.)” Sujit earns Rs. 350 which he says is maximum one can earn a day in the business of bamboo weaving. He travels to nearby blocks like Chhapwa to sell the products.

Ramsomari Mallik, in her 60s, is splitting bamboos. “We are called Mehtars. We have been removing faeces and weaving bamboos for generations,” she says. Her home, which is not in good condition, is still one of few pucca homes in the toli. “This was made under Indira Awas Yojana decades ago,” she adds.

Ramsomari’s husband is paralysed. She has three daughters; two of them are helping her in weaving. Chulbul Kumari, Ramsomari’s youngest daughter, studies in Class 6 in a government school at Sagar Pokhra. She says, “I feel disheartened when I see my mother working tirelessly. As it is summer vacation, I can help her with this.” “Bamboo weaving is not easy, it is difficult. I don’t want this traditional art to disappear from my family.”

OLD AGE PENSION, AWAS YOJANA FAR CRY

The mukhiya (village head), Ramsomari says, doesn’t approve vridha (old age) pension. Mukhiya Ravindra Kumar Ravi alias Ravi Painter left the village after learning that a news reporter has come to the village; he did not respond to phone calls.

None in the Dom Toli knows that Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar recently extended the pension amount for those who are in the age-group of 60-79 to Rs 400 per month while those above 80 years old are to receive Rs 500 per month as pension under the scheme.

“Ration ke chaur etna kharab dewela ki suaro na khai (The rice given to us is so contaminated that even pigs would not eat it),” says Rita Devi. She tells us that the ration is carted once in two months. Most of the families in Dom Toli cook food on wood fire as they can’t afford a gas cylinder every month.

Rita gave Rs. 15,000 gave to the mukhiya for releasing the Awas Yojana fund last year but was not provided with any receipt. She alleges some corruption angle. “I went to the municipality today and they assured us that our funds would be released within a week. It is exhausting. If we go to the municipality every day, who will do our bamboo work?”, she adds.

“Ketna sal se suna tani san ki Indira Awas pas hoyi, pas hoyi, lekin kuchhu naikhe bhail. (We all have been hearing since ages that funds of Indira Awas Yojana would be released; we have received nothing yet.),” Rita adds. She fears that speaking to media may further suppress the release of funds.

Like many others in Dom Toli, Shivakali’s life is also pivoted on the bamboo weaving. Shivkali Mallik’s son Rama Mallik died of a prolonged illness. “We visited the hospital and they gave us some pills; Rama became temporarily stable. One day, his condition deteriorated which took him away from us,” Shivkali says, “Look at this wall [behind Shivkali: Inset], two days ago bricks came crumbling down to the ground due to a rainy gale. Government is not releasing funds for the construction of the house”

“We are poor, how can we bribe them for Awas Yojana,” says Badlol Mallik who is cleaning the bamboo clum nodes in the front of his home. “Ihe noon roti ba (Bamboo is livelihood for us.)” He plans of making kharata brooms out of the bamboo clum.

Guddu Mallik says, “We had the livestock [pigs] worth of Rs 1 lakh. All of them died a few months ago due to unknown medical reasons. Each adult pig, Guddu says, is sold at a minimum of Rs. 8,000. “Pork’s price has now gone up to Rs. 200 per kg. Had there been pigs, our financial condition would have been better,” he adds.

Mehtars and Doms have been traditionally rearing pigs here. There are numerous pork stalls and pig slaughter centres.

“Badka log ke makan pe makan banata auri dom-mehtar-dhangad-mushar san bhukhe mara tare san (Rich are getting richer and Dom-Mehtars don’t even get ration from the government.),” exclaims Chandan Mallik, a pig butcher, whose Aadhaar card was not issued because the biometric device failed to register his disfigured fingerprint. “I am good enough for EPIC [voter ID] but not for Aadhaar.”

It has been three years since Chandan has received any ration.

Panna Devi is weaving dauras (baskets to be used in Bihari weddings) on the road. She has dipped some bamboos in sewage water. She says, “We don’t even have clean water to drink, how will we arrange water to dilate bamboo fibres.”

Each daura has a market value of Rs. 40 which requires at least one labour hour. Panna earns a net profit of Rs 150 after six hours of labour. She feels that bamboo weaving is underpaid, she also thinks of leaving this work but the fear of loss of tradition haunts her. “This is our ancestral work, how can we leave this?”

Kishore Mallik, who has a furnished house at one end of Dom Toli, tells us that his grandfather built it with the income he had from a government job. For him, caste is independent of class. Asked about any experience of untouchability in spite of being relatively well-off, Kishore confirms, “Yes, once I went to Areraj Malahi and I was prohibited from touching the hand pump by the upper caste people there after they came to know my caste” “They buy our daura and supli for the sacred festival of Chhath but don’t even let us touch their hand pump. They pour water into our hands maintaining a distance. In some villages, we are asked to go to Dalit basti to drink water.”

“Even if we dalits become rich, we will continue to be treated as low-born because of our caste,” says Kishore.