New Delhi: He has been trained in business administration, passed B.Ed. (bachelor of education) with flying colours, completed diploma courses in computer networking, designing, operations, calligraphy and manuscriptology, and could have worked as a business professional or IT professional or have become a teacher. But calligraphy was his call and is like worship for him.

Meet Imran Hayat, who has made a mark for himself at a global level. Belonging to Rajasthan’s Tonk district – the erstwhile capital of the eponymous princely state of British India — the 33-year-old is on a mission to revive the dying art form in India.

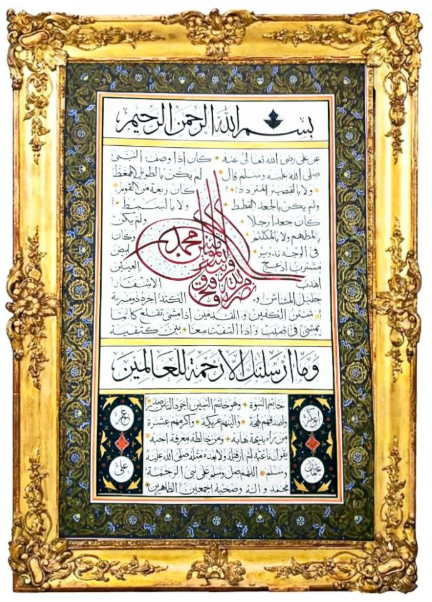

His works attract attention even if one is not familiar with Urdu, Persian and Arabic. The aesthetics and refinement, he says, are the specificities of Islamic art. “Writing the Quranic verses is worship,” says the calligrapher, who believes that the Arabic script is the most beautiful in the world.

Hayat has written 11 Quran by hand in various styles. He was associated with the calligraphy project of the mosque of Mecca (Saudi Arabia) where he was assigned the job of proof-reading the Quranic verses engraved on stone slabs.

His works on leather, cloth, wood, stones and paper have been greatly admired by people in India and abroad. His specific monograms (Tughre) in calligraphy have been awarded.

Having earned various degrees in higher education, Hayat kept learning the art of calligraphy. He pursued a course of graphic design in calligraphy in 2004, got a diploma in Arabic language in 2006, and also took training in manuscriptology in 2010.

Hayat says the art in India has been in continuous decline after the end of Mughal rule. According to him, calligraphy work in India was never recognised globally, as it was nowhere near international standards.

To make ends meet, Hayat takes projects from people and government departments that fetch him Rs 15,000-Rs 20,000 a month. “But this income is not regular. It depends on orders,” he says, ruing that the government was not doing enough to protect and preserve this art form.

“The government through the National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language organises exhibitions once or twice a year. Calligraphers are invited to exhibit their skills and are paid a meagre Rs 5,000-Rs 10,000. Tonk-based Maulana Azad Arabic Persian Research Institute, too, organises one or two exhibitions every year despite the fact that they offer calligraphy courses,” he says.

Hayat says calligraphy has played a special role in shaping his life. “It has given me recognition in the country and overseas. It has, in fact, given me a unique identity.”

Asked how difficult it is to learn this art, he says, “Calligraphy entirely depends on writing style. It needs accurate writing posture and enough patience. It slows you down but makes you enjoy the little things in life, which is much needed in the modern fast lifestyle. It requires a lot of practice and patience.”

Asked to share some anecdotes, he says, “It was not an easy journey. I have been practicing it since childhood. When internet wasn’t so common, I used to write headings for newspapers. The handwritten words were difficult to distinguish from printed newspapers.”

Hayat says it is disheartening to see the treatment calligraphy receives in India. “Our country still lacks appreciation for this art form unlike in other nations. Here it is not considered special or exceptional. This is heartbreaking. Calligraphy, too, is a form of art and should receive the same respect as any other art form.”

"Onus Lies on the Muslim Community"

Calligraphy is an Islamic art form, says Irena Akbar, a journalist-turned entrepreneur who runs an online firm of arts and craft – Baradari — which deals in home décor, adding that the onus lies on the Muslim community to buy and cherish this art because it is part of the Islamic heritage.

Asked if she feels that it is a dying art that needs government attention, Akbar says, “If you compare with the Mughal era, it (calligraphy) appears to be declining. It needs promotion. Its market is very limited. Its audience is also very limited because everyone does not know Arabic. And also because it basically targets Muslims. Of course, the market is limited but it has slow growth. I don’t think we should expect too much from the government. To protect Islamic art on architecture is the responsibility of the government. It can introduce calligraphy course in fine arts departments of different universities. But the Muslim community should do something for promoting and popularising this form of art. We are not a free market economy and, therefore, the government cannot be held accountable.”

On the challenges in her business, Akbar says people spend money on clothes and food, but not much on home décor. “I keep telling people through social media that this is a lovely piece of art, which is used not only to decorate homes but to gift somebody as well. We sell at affordable prices, but we cannot sell it at cheaper rates because it will lose its value,” she adds.