There is deep-rooted bias amongst India’s police force against it's own religious minorities, esp. Muslims, and this is not the first time that this has been brought to our notice. Seminal studies by noted academic Paul R Brass (Forms of Collective Violence—Riots, Pogroms and Genocide in Modern India, 2002, published later in 2006) argue on the systemic and institutionalised riot mechanism in India, that works to a pattern, against the Muslim community here.

Earlier in tumultuous 1990s, an IPS officer, Vibhuti Narain Rai, took time off from his duty to scrutinise, research and study not just attitudinal issues within the police force when it came to Muslims, but also the conduct and behaviour of Indian policemen when they were confronted with communal violence (1995). This was published in a book, titled Combating Communal Conflicts.

Now, in 2019, after the India of targeted progroms has changed to the everyday fear-mongering and hate violence of lynchings, a study by Common Cause – Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Lokniti has revealed disturbing prejudices of police personnel towards Muslims. The study has also highlighted prejudicial attitudes in the incidents of mob violence.

The idea behind the study titled ‘Status of Policing in India Report 2019’ was to “offer policy-oriented insights into the conditions in which the Indian police works.” Apart from other aspects, the report delves into sensitivities and service conditions of police personnel, their resources and infrastructure, patterns of their routine contact with common people and the state of the country's policing apparatus.

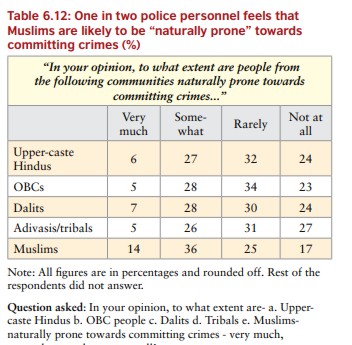

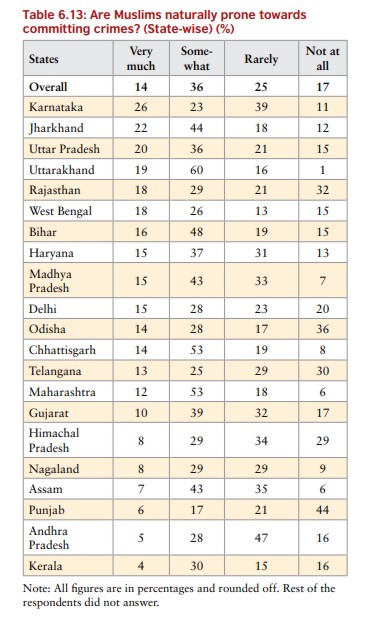

To study the attitudes of the police personnel towards various communities, the researchers asked the police personnel to what extent, according to them, were people from different communities, castes, religions, economic and educational backgrounds naturally prone towards committing crimes. It interviewed 12,000 police personnel from 21 different states.

The report highlights an evident bias in attitudes towards Muslims as a community, when it came to the question of committing crimes.

It observed,

“When we looked at what the police personnel think about various communities, the data indicated a significant bias against Muslims. However, no such prejudices were reported against people from SC or ST communities. About half of the police personnel reported that Muslims are likely to be naturally prone towards committing violence (‘very much’ and ‘somewhat’ combined). We observed similar trend in the reverse direction as well, with less number of police personnel likely to report that Muslims are less likely to be naturally prone at committing violence as compared to people from various caste-groups”.

Studying the pattern decades earlier, Brass in Forms of Collective Violence: Riots, Pogroms, and Genocide in Modern India wrote:

In the long, previously unpublished essay on “The Politics of Curfew”, I have provided extensive, detailed accounts from my own interviews over many years, as well as from other sources, concerning the misuse of curfew in India as a device for the victimization of the Muslim population during riots. In preparing that essay, I searched for comparative literature on the subject and found none, but I did find evidence that misuse of curfew restrictions to victimize particular ethnic or subject groups is hardly confined to India. I have, therefore, argued that this is an issue that needs to be taken up by the human rights community and international organizations. I have also proposed a set of policies that might be considered by such groups and by governments in India.

The last essay in the collection takes up the issue of what secularism means in India in relation to collective and state violence involving Hindu-Muslim relations. I argue here, as I have elsewhere, that secular values are absolutely essential for the maintenance of a just peaceful social order in India. I believe, moreover, that the whole movement against secular values in India and the West is a grave mistake in which, regrettably, many valued colleagues and serious academic writers in India and the West are involved.”

Similarly, in his preface to the book, Combating Communal Conflicts, that was then published in 1999, Rai writes:

When I got an opportunity to study the behaviour of Indian Police during communal riots as a fellow of the SVP National Police Academy, Hyderabad, I did not realise that my work could be so interesting and challenging. The more I immersed in the research, the more I became aware of my limitations. The biggest limitation was the difficulty I experienced in trying to overcome the mental barrier of the average policeman. Most of the Police Officers and men with whom I had an opportunity to interact were convinced that most effective way to control or prevent a communal riot was to adopt harsh measures against the Muslims. Almost all of them, with very few exceptions, were of the view that Muslims were responsible for starting riots and, therefore, the most effective way of preventing them was to deal harshly with that community. Perhaps, this is the reason that events like Hashimpura (1987, Meerut) or Logain (1989, Bhagalpur) where the police killed more than 30 innocent members of the minority community or allowed more than 100 to be slaughtered by those belonging to the majority community are not able to create any feeling of repentance and are even justified with forceful arguments. It was this mental barrier that prevented me from gaining access to many police documents that would have helped this Study.

As a Police Officer, it is my firm belief that unless we come to terms with the fact that we have been committing colossal blunders in dealing with communal riots, we will continue to repeat our mistakes and continue to be put in the dock. Unfortunately, the Police leadership is not prepared to accept these mistakes. I think this is the reason that in spite of the fact that it was the SVP National Police Academy that gave me the fellowship to undertake this Study, it refused to publish my findings. I am thankful to the LBS National Academy of Administration. Mussoorie for having taken the initiative in publishing my study. I would specially like to thank Shri N.C. Saxena, IAS, Director. LBS National Academy of Administration. Mussoorie for having taken the decision to publish it.”

Gujarat 2002’s genocidal pogrom against India’s largesst religious minority took this entrenched prejudice to new levels. Yeh andar ki baat hai, Police hamare saath hai! (It’s an inside story, the police is with us!) was the much-heard boast of the Sangh Parivar cadre in Gujarat at the time. Former ADGP (Intelligence), Gujarat, RB Sreekumar, who bore witness to the 2002 pogrom, had spoken to Communalism Combat on the trials & tribulations of taking a Constitutional stand. He still faces persecution from the powers that be.

Now, the study by Common Cause – Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Lokniti makes a similar point. Police personnel in the four states surveyed – Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, Maharashtra and Bihar – had about two-third or more police personnel who held the opinion that the Muslim community was likely ("very much" and "somewhat" combined) to be naturally prone towards committing violence. Four out of five police personnel from Uttarakhand were of this opinion.

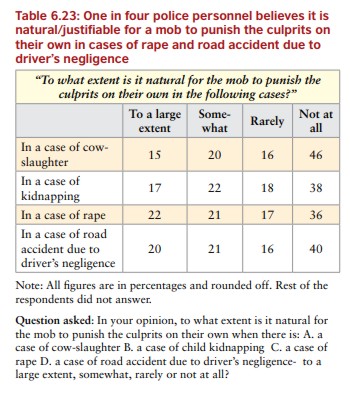

Similarly, disturbing patterns of biased attitudes emerged in the cases of mob justice as well. In recent years, numerous cases of mob violence against individuals (sometimes referred to as ‘mob lynching’) on suspicions of cow-slaughter, kidnapping, etc. have been reported, and the police is known to have played an enabling role for the people engaging in such forms of violence. This merits the need to understand police personnel’s opinions on the public taking matters into their hands over issues that cause moral outrage, such as cow slaughter or rape or kidnapping. On the other hand, a relatively neutral category of crime such as road accidents caused due to the negligence of the driver has been taken for the purpose of comparison.

The study attempted to analyse the attitude of the police towards the nature of crime and justifiability of a mob in punishing the culprit. The researchers asked the respondents to what extent is it natural for the mob to punish the culprits on their own in four situations- in a case of cow-slaughter, in a case of kidnapping, in a case of rape and in a case of road accident due to driver’s negligence. They said, “…a relatively neutral category of crime such as road accidents caused due to the negligence of the driver has been taken for the purpose of comparison”.

Shockingly, more than one in every three police personnel believed that it was natural for a mob to “punish” the alleged culprit in a case of cow-slaughter (‘to a large extent’ and ‘somewhat’ combined). While in the case of the three other cases of crime, two in five personnel believed so.

This meant that while a little less than half believed that it wasn’t natural for the mob to punish the culprit in case of cow-slaughter, while more than half found it natural, either to a “large extent” or “somewhat” or “rarely”. In case of other three types of alleged crimes, about 6 to 10 percentage points lesser people were found to believe the mobs’ action to be not natural at all.

The study also found out that “for all the four cases of mob-violence, the senior officers are less likely to believe the action of mob to be natural compared to their subordinates (constabulary ranks)”.

It observed, “While 28 percent of seniors were found to believe the mob violence in case of cow slaughter to be more of natural (‘to a large extent’ or ‘somewhat’), the proportion of subordinates were found to be 8 percentage points higher. In the three other cases of mob violence, this difference was found to be around 10 percentage points”.

Among the respondents who were in complete disagreement (responding as ‘not at all’), the respondents at the officer level ranks were in higher proportion, 10 percentage points higher, compared to the respondents at constabulary ranks.

The report emphasised on the need for “proper training in essential aspects of the rule of law at all levels in order to inculcate constitutional values and rational conduct among police personnel”.

A deeper analysis reflected that Madhya Pradesh was found to have two in every five and Chhattisgarh, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh about one in every four believing it to be very natural for a mob to punish the culprit in case of cow slaughter. Seven of the States had less than one in every three believing it to be not natural at all for the mob to punish the culprit.

The report –the latest in a long line of similar studies—has alleged that a significant proportion of police force has a casual attitude towards incidents of mob violence, believing it to be natural for the mob to take law into their own hands. While majority of police personnel were found to have received the trainings in human rights, caste sensitisation and crowd control, for a large section of the police, this training was only imparted at the time of joining.

The study documents that,

“These attitudes and opinions could therefore be a reflection of the lack of proper and frequent trainings. Such training, if provided regularly using proper modules, might help not just in softening their preconceived notions towards vulnerable sections of the society, but in also ensuring that such biases do not interfere with proper functioning of the police. An institutional bias against the marginalised sections further increases the vulnerability of these groups. A healthier police-public interface can only be achieved when these prejudices are attacked and due process is established. Thus, there is an urgent need for the police to come out of the web of societal prejudices and prove itself efficient in upholding all the rights provided by the Constitution of India”.