In June 2019, teams of student volunteers and local co-workers visited a dozen Anganwadis each in rural Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh. This exercise was part of the Jacha-Bacha Survey 2019 (JABS), a study of maternal and child care in rural India coordinated by Jean Drèze, Reetika Khera and Anmol Somanchi.

Using their shared observations and the survey footage, some of the volunteers made a short film, The World of Anganwadis. The video dives into the nooks and crannies of rural India, where a quiet battle for the rights of Indian children is taking place.

Is it a tale of despair or hope? You decide.

The World of Anganwadis

Background:

The Anganwadi (child care centre) is a bridge that connects the government with pregnant women, nursing mums and children under six. Since 2006, under the Supreme Court’s orders, Anganwadi services are legal rights of all Indian children.

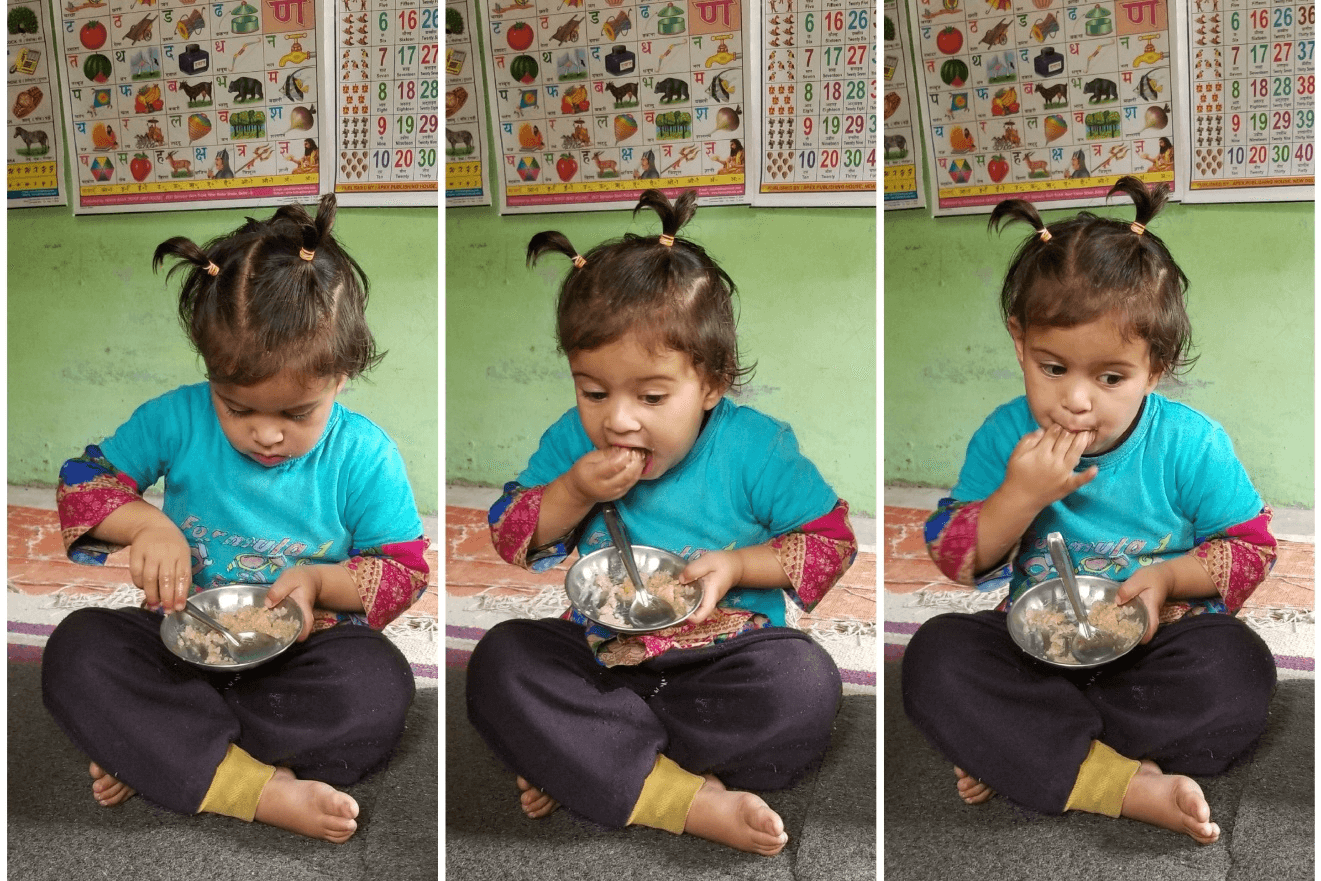

Under these far-reaching orders, every village is supposed to have a lively Anganwadi, where children below the age of six years receive some good food and healthcare, not to forget pre-school education: games, songs, poems and drawings, all of which can help develop a child’s learning abilities and interests.

The Supreme Court declared all children below the age of six years to be entitled to all ICDS services. The government of India was directed to set up fourteen lakh Anganwadis in a phased manner within two years. Settlements with at least forty children below six years but no Anganwadi were entitled to a centre on demand.

Anganwadis also supplement the nutrition and food security entitlements provided under the National Food Security Act 2013. For example, JABS 2019 found some Anganwadis where pregnant women were served cooked meals—this is a legal right under the NFSA.

Two field-based reports shed useful light on the status of Anganwadis: the Focus on Children Under Six (FOCUS) report, released in 2006 (in Hindi here), and the Progress of Children Under Six report, released in September 2016. POCUS revisited the districts studied in the FOCUS report and examined how children upto six years old were doing under the ICDS scheme in six states.

The ICDS scheme provides a range of health services including immunisation, growth-monitoring and health check-ups, along with hot cooked meals for children aged three to six years, take-home rations for children aged 6 months to three years and for pregnant and nursing women.

FOCUS had found that Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu were “active” states. They were implementing the ICDS programme relatively well. The other three states, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, were classified as “dormant”, as they had not extended the ICDS programme beyond the most basic food supplements.

FOCUS, conducted in 2014, was relatively encouraging in that two of the formerly dormant states, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, had a much more active ICDS programme by then. Uttar Pradesh, alas, was still far behind.

Taking the six states together, by 2014, significant improvements were evident in the quantity and quality of food supplements, the regularity of child attendance, the maintenance of growth charts, and related matters.

Consider the proportion of sample mothers (young mothers with a child registered at the local Anganwadi) who stated during the POCUS study that their child attends the Anganwadi regularly: it was 80% or more in 2014, compared with 40 to 50% in 2004. Similarly, the proportion of mothers who reported getting immunisation services at the Anganwadi rose from 48% to 84%.

The proportion of mothers sampled who felt that the ICDS is “important for their child’s welfare” increased from 48% in 2004 to 84% in 2014. The fact that quality improvements took place during a phase of rapid quantitative expansion is good news.

Cut to 2019 and the JABS Survey:

JABS 2019 finds that the ground realities of Anganwadis still tell a different story depending on where you go. In Uttar Pradesh, apathy and corruption have not spared the programme. Most Anganwadis in the state are still idle and gloomy, when they are open at all. In Himachal Pradesh, on the other hand, many Anganwadis are a joy to see—lively, colourful and well-managed.

In between these extremes, many states are doing much better than Uttar Pradesh, but are still a long way from giving children their due. What gives hope is the experiences of poor states such as Odisha, where, thanks to years of patient work, Anganwadis are beginning to resemble those of leader states like Himachal Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

Shaping the Future:

The future of Indian children, and indeed of the country, is being shaped in the modest premises of Anganwadis managed by local women.

In most states under the JABS study, pre-school education seemed to be picking up. Himachal Pradesh and Odisha governments had provided all the surveyed Anganwadis with pre-school literature. In Uttar Pradesh, however, pre-school education at the Anganwadi was still a fiction.

In Odisha and Himachal Pradesh, all Anganwadis were serving breakfast and lunch. In Uttar Pradesh, the sample Anganwadis were not providing even one cooked meal to children–they were still relying on a very unpopular ready-to-eat mixture, often fed to cattle.

In Himachal Pradesh, Anganwadis are doing so well that they resemble pre-schools. Sixty per cent of the Anganwadis in the state did not require any repair. But in Madhya Pradesh, 77% of the centres needed some repair. Children in Madhya Pradesh do not get uniforms, though footwear was being distributed to them at the time of the survey.

Image courtesy Reetika Khera and Raghav Puri

Image courtesy Reetika Khera and Raghav Puri

Some Anganwadis in Himachal Pradesh and Chhattisgarh also provide baby kits with blankets, mosquito nets, thermometers, first-aid kits and tiny bottles of baby oil, talc and soap. Children learn to wash hands before eating, queuing up, being tidy, using a spoon, drawing and painting and other crafts in them.

In several states, the health department sends the ANM and ASHA workers to Anganwadis on fixed dates, which is another sign of improvement. ANM and ASHA workers link women and children in the village and its Anganwadi with other government healthcare services and schemes. JABS 2019 found women being provided ante-natal care in Lalmati, Chhattisgarh, where the ANM visits on a fixed date, registers new pregnancies, weighs expecting mothers, checks their blood pressure, provides tetanus and typhoid injections, and so on.

Budget:

There is some econometric evidence of the impact of the ICDS on child nutrition, child education and related outcomes from recent studies by Gautam Hazarika, Monica Jain, Eeshani Kandpal, Nitya Mittal, Arindam Nandi, and their colleagues, among others. The second Indian Human Development Survey and Rapid Survey on Children also point to a marked acceleration in the progress of child development indicators after 2005-06.

The central government, however, has been going slow on ICDS in recent years. There was a huge setback in 2015-16, when the ICDS budget was slashed. The budget for Anganwadi services today (a little below Rs 20,000 crore) is more or less the same, in real terms, as in 2013-14. It is grossly inadequate to meet the multiple demands made on the ICDS system.

The allocations therefore reflect social priorities of the central government. The stagnant allocations for child services send a signal that could cause much damage down the line.

Note: The JABS findings on maternity entitlements have been widely discussed. More detail is available here.

This note was prepared with inputs from Jean Drèze, Reetika Khera and Anmol Somanchi.