Even the worst critics of Prime Minister Narendra Modi will concede that he is a great communicator. His forceful speech in Parliament on 6 February 2019 in defence of the controversial Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) was a brilliant act of political messaging. It reminded me of what the historian Lord Acton had famously said: reforms far from averting a rebellion tend to precipitate it. Modi was Actonian at his best. In response to mushrooming anti-CAA protests across the nation, he not only displayed his energetic defiance, he also reconfirmed his commitment to the CAA.

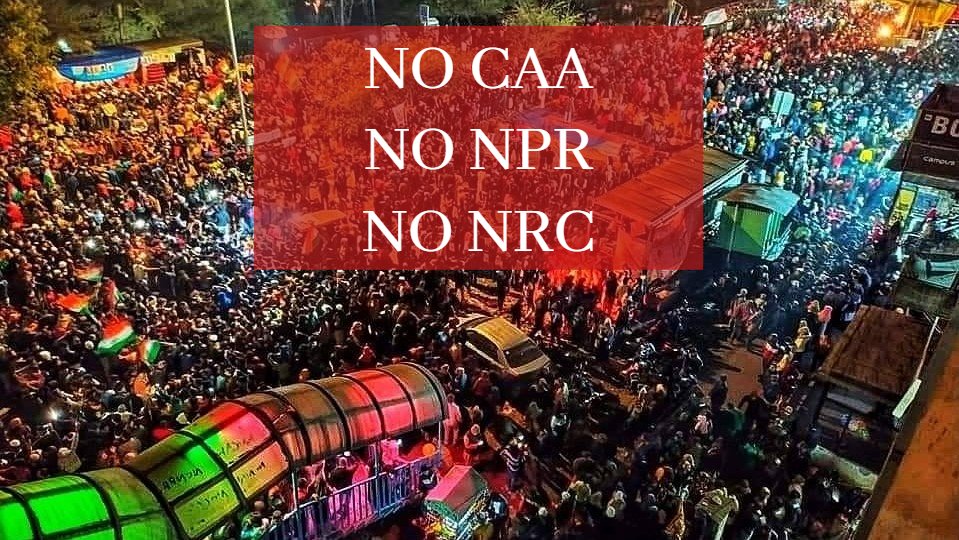

It is not easy to write on contemporary politics for a historian like me. Politics is existential; history is transcendental. Therein lies my problem with the BJP’s vision for the CAA/NRC/NPR. They justify it purely in contemporary terms, with little regard for the subcontinent’s longer history and with a very limited vision for the future. To my understanding, the situation is much more complex: It requires acknowledging the challenges that a plural post-colonial society like India has to confront and, more importantly, it requires us to recognise that we as a society are the product of human migrations through all times and climes.

Thus, when the BJP claims that it is fulfilling the unfinished task of the Partition, I am forced to look for other such claimants.

The original nation-builders of India, in the forefront of whom were the Indian National Congress under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, had felt their task incomplete unless India became an inclusive and secular democracy. For the new-born Pakistan, its unfinished task was the incorporation of Kashmir into the Pakistani state. For Hindu nationalists, their unfinished task was to make India a Hindu rashtra and, if possible, delegitimise the Partition and re-establish ‘Akhand’ Bharat (undivided India). These unfinished tasks are the long-standing demons that fuel today’s CAA, which we cannot delink from the NRC despite the BJP’s mendacious protestations.

Cross-national movements of people are in South Asia’s DNA. Add to the mix poverty, illiteracy and widespread corruption, and the massiveness of the task of citizenship certification becomes readily apparent. The cases of Abu Hanif alias Millan Master v Police Commissioner of Delhi and Others (2000) and Abu Hanif alias Millan Master v Union of India and Others (2001) provide interesting examples. Abu Hanif was an Indian Muslim, yet he was accused of being an alien since he lived among Bangladeshis. He faced immediate deportation to Bangladesh. The court, however, gave the verdict in his favour. The flip side of the same phenomenon also exists. It is easy to acquire citizenship by manipulating the system and becoming what Kamal Sadiq has called ‘paper citizens’.

Let us take three recent experiences to see what different ramifications the institution of ‘paper citizens’ can assume in the Indian context: One, Hindu paper citizens in Jammu and Kashmir; two, Indian/Plantation Tamil paper-non-citizens; and three, paper refugees.

One of the arguments put forward by the Indian government while diluting Article 370 in J&K was that it would allow Hindu refugees from Pakistan who had settled in the state to become full citizens of India. According to the BJP, these refugees had long suffered from the handicap of not being state subjects. But as it turns out, most of these refugees had already managed to become J&K subjects in the intervening period. In 2018, when a scheme was announced to provide one-time financial assistance of Rs 5,50,000 to each of 5,764 such families, there was not a single taker. A one-time financial windfall was poor enticement if it might jeopardise their cleverly-earned J&K—i.e. Indian—citizenship.

The experience of Indian/Plantation Tamil expatriates from Sri Lanka offers us a second example, that which I call the story of paper-non-citizens. As a consequence of the Shastri-Sirimavo Pact of 1964 and the Indira Gandhi-Sirimavo Pact of 1974, thousands of these Indian/Plantation Tamils were expatriated against their will and settled in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh (including present-day Telangana). Half a century later, they and their descendants continue to lead miserable lives. Most of them have no idea where their citizenship certificates are. And what papers they had, were washed away in the 2019 floods. Now, multiply this story a hundred times over and we begin to get a sense of the plight of East Pakistani/Bangladeshi migrants in the states of Assam and West Bengal.

Our third experience is what I call the case of ‘paper refugees’. These are people who have submitted their papers but been told that these papers are incomplete. Following the NRC exercise in Assam, we have now identified 19 lakh such people as non-Indians. Among them, 12 lakh are Hindu, six lakh are Muslim, and one lakh are tribal (Christian?). If the CAA is taken to its logical end, only six lakh Muslims will remain as non-Indians. They would effectively be so-called paper refugees, the Hindi word for whom would be the obnoxious ghuspaithiyas, who, like ‘termites’, would be blamed for poaching into India’s resources.

Given that West Bengal is three times as large as Assam, India will soon have 20 lakh paper refugees. Although 20 lakh is just 0.14% of India’s 137 crore population, the number is large enough to jolt West Bengal politics when the state goes to the polls in 2021.

In the midst of all the controversy that a nation-wide NRC has kicked off, a recent Indian Express report offers a timely reminder of the challenges in store. In 2003, the Atal Behari Vajpayee government conceived a pilot project to test the feasibility of issuing Multi-purpose National Identity Cards (MNICs). The pilot project covered about 31 lakh people in 13 districts spread across 12 states. After six years, the exercise was given up, having achieved only 45% of the target. It was found impossible to gather information from rural people, especially those who were agricultural labourers, landless farmers, married females, or floating migrants in search of livelihood in towns and other villages.

My years of training in International Relations research have taught me two things: One, a state, any state, is a congenital liar; and two, statecraft is essentially amoral, in which taking the people for a ride is business as usual. Insofar as the first is concerned, the BJP is already a past master. In respect of the second, however, especially compared to the Congress, it has yet to master the art of statecraft. Let me give three examples.

One, the abrogation of Article 370 by the Modi government. By 2019, the article had already been fiddled with so much that it was hardly recognizable. Barring the abolition of the state through its bifurcation into two Union Territories, the BJP did nothing that Nehru and his successors hadn’t already done, including imprisoning the tallest leader of the state, Sheikh Abdullah. To my pointed question to the Kashmir University professor Aijaz Ashraf Wani, the author of a 2019 scholarly study, What Happened to Governance in Kashmir, “Which party has been worse for J&K, BJP or Congress?,” his categorical answer was: “Congress”. But this was before the Modi government had abrogated Article 370. Wani may give a more nuanced answer now. Howsoever the Modi government might claim that normalcy has returned to the Valley, the situation remains grim and far from normal. To repeat: Statecraft is a complex business; it is not merely playing to one’s gallery.

Two, the Indian state under the Congress was also pro-Hindu, its avowed secularism notwithstanding. For example, when in the fifties and sixties some controversies arose in Assam in respect of Hindu and Muslim immigrants from East Pakistan, a 1965 secret administrative order of the government of India authorised the district magistrate to grant Indian citizenship to those Hindu refugees from East Pakistan who had settled in Assam for six months or more. It did not attract anybody’s attention as a non-secular move. Similarly, it cannot be just a coincidence that prior to the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits from the Valley in 1990-91 most of the positions in J&K’s nationalised banks (such as SBI), AG Office, Post Office, etc. (all controlled by the central government) should be manned almost entirely by them. I suspect that there must have been an unwritten instruction from the central government in this regard as well.

Three, Modi government itself undid in its second term in office (May 2019-) that which it had so surreptitiously achieved in its first (2014-19). Through critical changes in the administrative ‘rules’ (not ‘Amendments’) pertaining to Passport (Entry into India) Rules, 1950 and the Foreigners Act, 1946, Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and Parsis were given preference vis-à-vis Muslims in respect of naturalization, or putting in detention centres. The imperatives behind the CAA, therefore, are not new. But as a duly passed Act (and not mere ‘rules’), it has raked up an avoidable controversy because it had to be done through the parliament. It is probable that other calculations were in play, most notably the BJP’s desire to make inroads in the 2021 West Bengal election, and in broad sense pamper its Hindu constituency. If so, it would not be statecraft but politics, once again aimed at playing to the gallery. Sheikh Hasina Wajed is right when she says that the act was ‘unnecessary’.

Postscript: Raja Deen Dayal was probably India’s first photographer. Between 1884 and 1905, he produced over 30,000 images of architecture, landscapes, and people. The sixth Nizam of Hyderabad appointed him court photographer. His studio became the first Indian firm to receive a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria. In his collection, recently on display in Delhi, there is a family photo of a Hindu nobleman of the Nizam’s court by the name Pershad. This Pershad is shown with his several wives, both Hindu and Muslim. The photo also depicts a large number of children. Those born to Hindu mothers are wearing Hindu attire; those born to Muslim mothers are wearing Muslim attire. Setting aside our concerns over polygamy, is not the photo evocative of the possibilities of South Asian secularism, whose key defining feature remains its tolerance?