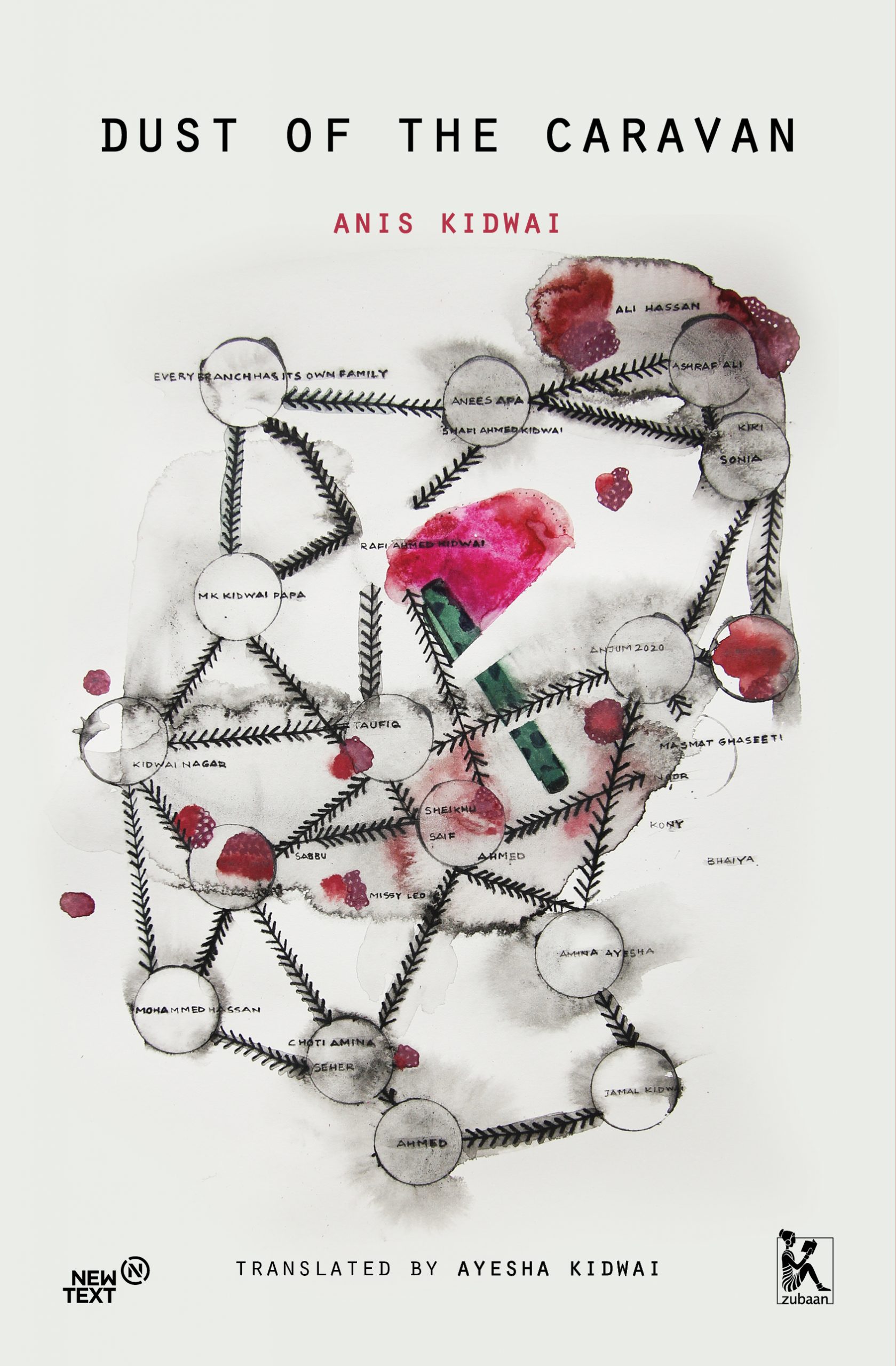

Translated by Ayesha Kidwai, Dust of the Caravan is a selection of writings by Anis Kidwai sketching the personal and political journey of a Muslim woman through the first eight decades of the 20th century.

Simultaneously a social history of life in rural Awadh in the early 20th century and the birth of the national movement in the region as well as an account of the traditions of mutual respect and understanding between different faiths in a shared culture and the rupture of those very traditions during Partition, this book is also the story of a woman’s journey from the home into the world and from “family values” towards autonomous beliefs, friendships, and activism.

Amongst the dream-like memories there is also one of an evening in which my Buā has my younger brother in her arms and I am walking alongside them. At a short distance from the house, I see a dirty bundle of clothes lying on the road and I give it a kick. The bundle groans loudly, and my Buā exclaims, ‘Hai! What are you doing?! You don’t kick a human child, do you?’ She sits down besides it and starts speaking to it. In response, the bundle of rags unjumbles. At first, two pairs of arms and legs, burning hot, appear, and soon we are on our way home, a dirty young girl tottering along with us.

The girl was quite a bit older than me, but I went about the house preening—she was my ‘discovery’, the one I had found and brought home. Her fever came down with medicines the very next day and my mother herself stood by and supervised as one of the women servants gave her a bath with water, soap, and besan. The grime and dirt were rubbed off of her with potshards. With a kurtā from one person, a paijāmā from another, a pink oṛhni draped on her, that pitch-black girl was soon transformed into a comely one with large eyes and golden skin the colour of wheat.

Just a few days of a regular diet brought out her beauty even more, and within a month, this twelve- or thirteen-year-old girl was always to be found teasing and flirting with the other servants. We named her Nargis. I was very happy and pleased with her and kept her by my side always.

One day, Nargis accompanied me to the part of the house where the cousins who were living with us for their studies, resided. I don’t know what exactly happened, but soon little pebbles started flying around, and peals of laughter bubbled in the air. I felt compelled to go report to my mother that Nargis was throwing stones. The next I knew, Nargis was given a few slaps and ordered never to even think of making her way to that side of the house ever again. And shortly after, she was sent off to my nānī’s home for education and training.

It was one year later that she returned. In her colourful gharārā, shining with gold trim and embroidery, and the red dupaṭṭa she wore around her shoulders, she was now a married woman. A dim-witted young man was by her side, and he was at once engaged by our family, and sent off to Aligarh to serve Rafi sāhab.

Once I said to Nargis, ‘Your husband is calling you.’ My words were greeted with a loud snort and a gob of spit. She detested him. And though she stayed with us and grew more beautiful by the day, she never gave that husband of hers a second look. The truth was that she had eyes only for one manservant of ours, handsome in his beplumed turban. Eventually, one night, Nargis disappeared altogether.

It was only three years later that she returned. We all surrounded her, delighted to see her. She now swore by Our Father and Jesus Christ and wore a skirt. The Christian missionaries had inducted her into Jesus’s flock of sheep and had taught her to say, ‘Oh Heavenly Father, let your will be fulfilled on earth as it is in heaven, and give us our daily bread.’

We brothers and sisters pleaded with her, ‘Nargis come back to us!’ And to our delight, she agreed. However, now her manner was quite brazen. After a year or so of revelry, she decamped with the magnificently turbaned manservant. The next year this esteemed employee was sighted in the mela at Dewā, dressed in saffron robes, now a self-declared pīr, but Nargis never returned. And we never got any further news of her.

For everyone else, Nargis soon became long-forgotten, but her memory has always remained in my heart. Today when I am concerned with the education, reform, and improvement in the lives of the girls in the Women’s Service Home, I think of Nargis again. If only we had afforded her some ease and facilities, her ruined life could have been repaired.