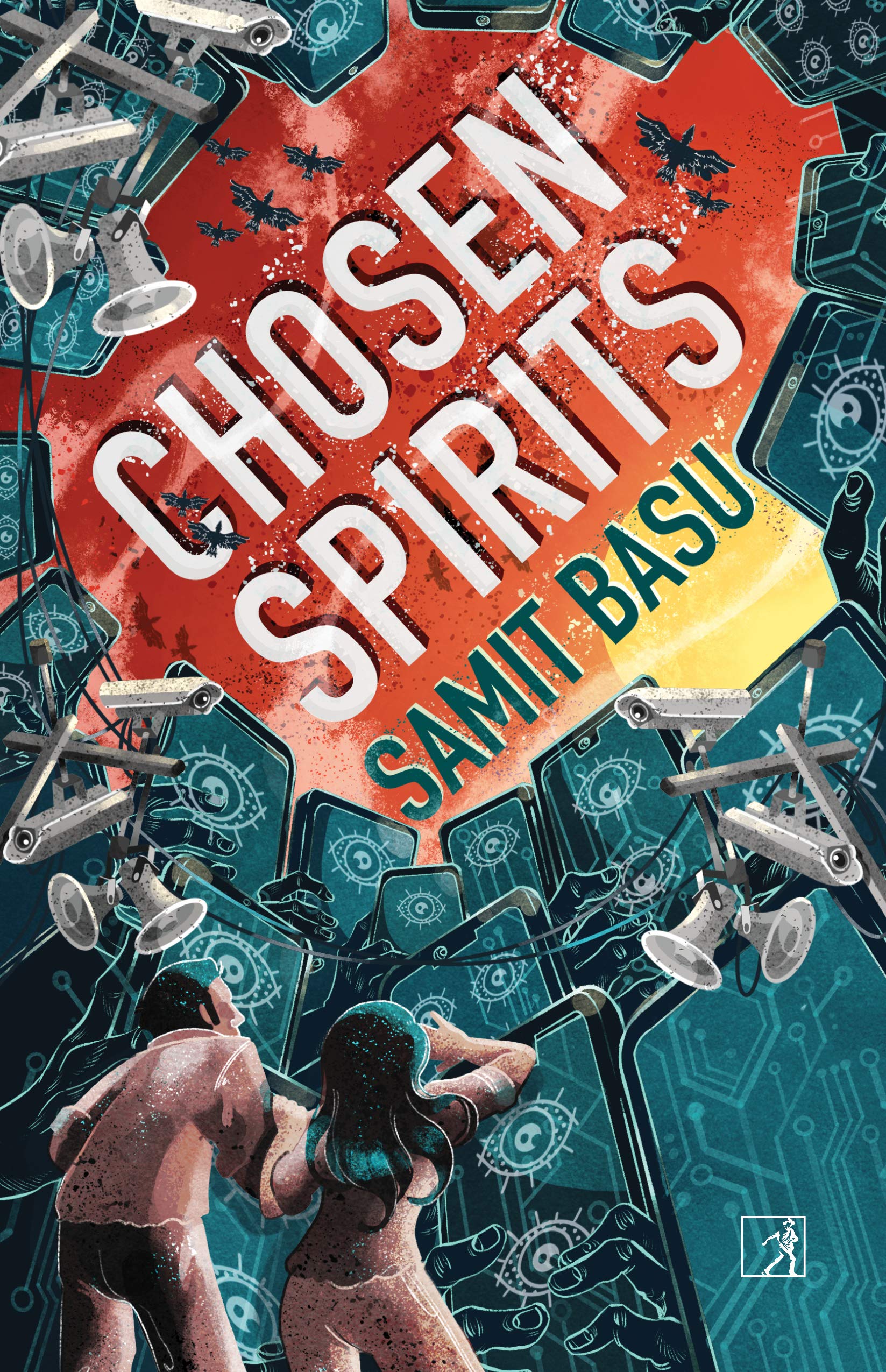

Samit Basu’s Chosen Spirits is set in a Delhi that’s around ten years from now, in the end of the 2020s. The work exists somewhere around the margins of dystopian fiction, science fiction, and political satire, and is told from the perspective of the dynamic metropolis. Built through news headlines and the palpable, disturbing presence of surveillance all around, it’s a call for freedom and resistance. At a simpler level, its the story of Joey and Rudra, as they “reckon with people and forces beyond their understanding, in a world where trust is impossible, popularity is conformity, and every wall has eyes”.

Here is an excerpt from the first chapter of the book.

Sometimes Joey feels like her whole life is a montage of randomly selected, algorithm-controlled surveillance-cam clips, mostly of her looking at screens or sitting glazed-eyed at meetings. As a professional image-builder and storyteller, she finds the lack of structure even more offensive than the banality of the material. She’s always taken pride in her instinct for cuts and angles and rhythms in the wildly successful stories she produces—one day, one perfect day, her life will be just as award-worthy. As she heads into the park near her parents’ house for her regular Sunday morning run—actually the first in three months, but she’s finally managed to wake up early this time, it’s usually way too hot to be outside the house by the time she reaches Little Bengal for her weekly visit she finds herself idly building another montage in her mind. A classic training sequence, where she builds an incredible body through first failing and then succeeding at the same task, intercut with determined running, some weights, an optional animal sidekick, rounded off with a motivational hope-hop soundtrack. Even the idea is tiring, and she considers going straight to her parents’ house, it’s already hot enough to make her eyes twitch.

Instead, she goes through her fitness checklist: headphones in place, cooling sportswear hopefully working as much as possible in Delhi, smog mask already making her face sweat, water bottle and pepper spray in the right slots on her smartbelt. A few stretches, and she’s off along the jogging track, keeping a wary eye out for battling stray dogs and monkeys lurking in the trees. The track’s distance markers are all in place: the fascist uncle laughing club shouting religious slogans while leering at her, the neighbourhood wives ambling along in large groups shouting to be heard over the blaring music on their phones, workers attempting their weekly repair of the park’s mysteriously smashed surveillance cams.

She sees the kolam on her third lap, when she slows down for a second to catch her breath. It’s a simple one, a basic floral pattern with embedded hashtags drawn on a cement patch next to a manhole cover in blue chalk. Joey quickly checks to see the nearest park cam is disabled, takes a picture of the kolam, and uploads it to a decoder app which tells her in a second about the protest it’s an invite for: another slum is being evacuated by the police and builder militia. It’s not far, it’s the neighbourhood where Laxmi, her parents’ domestic helper, used to live before she moved to Kalkaji with her boyfriend, a Cyber-bazaar shop-owner. The app tells her this protest’s potential bloodshed rating is ‘Extremely High’. There’s a cheerful wiggly blood-drop icon.

On her wrist, her smartatt pulses: a stress alert. The smart tattoo’s a new design, her skin’s still red around it. A cute elephant butt pattern that amuses Flowstars and makes funders think it’s a Ganesh tribute—Joey has always known how to bridge worlds. She rubs her wrist to stop the alert, but her Narad has woken up on her phone.

—Joey, good morning, are you all right? she messages.

Joey gestures at the phone, I’m fine, go to sleep, but Narad sends her a stream of loving emojis and virtual hugs.

—Should we go through some basic stress-relief exercises

and techniques?

—No.

—I see you are at the park. Great work on your daily step-

count! Should we do some fun yoga?

—No.

—I have set up a loveable dog GIF blast every half hour.

You are loved.

Joey pockets her phone and takes a few deep breaths. But it’s too late: as her playlist starts up again, the beat is exactly the same as the drums that were playing at the protest she’d been to, and she’s right back there, hearing the students chant, wishing she knew all the words, staring in growing fear at the riot police amassing behind the barricades, at the water cannon behind them.

She’d been fifteen, and her first board exams had been around the corner, so her mother hadn’t wanted to take her along. But her father had insisted: ‘This is a historic moment, and she needs to be out on the street, she needs to see there are people like us there,’ Avik had said. The protest was at Jantar Mantar, against the first wave of discriminatory citizenship laws, and their privilege had kept them perfectly safe. She’d made a poster, something meme-friendly, she can’t even recall what it was. What she remembers most was the energy: young men and women, not much older than her, rising up with the tricolour to try and save the country, the Constitution, the unity that India was founded with… that the regime was trying so hard to destroy. Her parents had seemed strangely thrilled—that evening, after an epic journey home in the cold, they’d explained they’d thought they were alone, that most people in the country had been swallowed up by a tide of bigotry and hate. They’d never been happier being proved wrong.

She’d gone to a few more protests with her parents, before they’d insisted she stop coming along and focus on her studies, and they’d all pretended this had nothing to do with large-scale attacks on students around the country, that Avik and Romola hadn’t held each other and cried when they watched news of police storming hospitals and libraries, that images of battered and blood-drenched students hadn’t flooded Joey’s private messengers. That things weren’t about to get a lot worse. That a day wouldn’t come, soon after, when Joey wasn’t allowed to leave her house and her parents didn’t know whether to blame the pogrom or the pandemic, because they’d known the end times were coming but hadn’t known they’d be multiple choice.

But a decade later, Joey’s memories of those days are happy and hopeful, full of an energy and a sense of belonging she hasn’t felt in years. It had taken a day for her to become an expert on identifying propaganda and its unlikeliest distributors. She’d quickly learned the words to ‘Hum Dekhenge’ and all the trickiest protest chant —she still remembers them, though she’s smart enough not to say them out loud. She’d held her mother’s hand at a reading of the Preamble to the Constitution at India Gate, while news filtered in of police brutalities and illegal detentions at a less privileged march. They’d brought in that new year at Shaheen Bagh, with a crowd of people, all ages, all religions, all classes, standing together, singing the national anthem, reclaiming the flag Joey had wanted to go and sit with the women at the heart of it all, the now-legendary women of Shaheen Bagh, wanted to go sit with her mother and be offered biryani and companionship by strangers, and huddle under a blanket and sing songs of hope and revolution. But there had just been too many people between them and her. They’d stood at a bonfire, watching their breath steam, wrapping their gloved hands around warming cups of tea. There were doctors and volunteers and biscuits and packets of medicine and students with candles, and signs in many languages, and more strength and solidarity and heartbreak in the air than Joey could breathe in.

She’d decided, that night, that she wouldn’t leave. That she would stay in India, in Delhi, and belong as hard as she could.