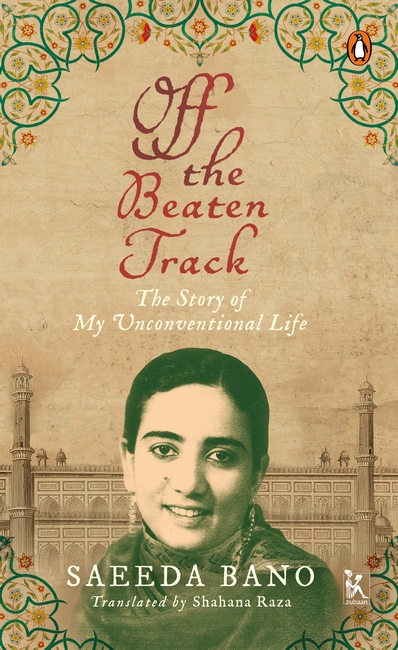

Saeeda Bano’s memoirs live up to their title, Dagar sé hat kar, ably translated by Shahana Raza as Off the Beaten Track. The book recaptures, with immediacy and vividness, the story of a life that also encompasses the changing social mores of the twentieth century. Raised in Bhopal, a unique city and kingdom ruled by a succession of women, Saeeda Bano spent most of her adult life in Lucknow and Delhi. Along with a flavourful rendering of these locations, she gives readers an intimate, thoughtful portrait of her failed marriage and of her subsequent life as a single woman and professional – the first woman newsreader on radio – who went on to find love and independence in her relationship with a married man.

The following extract is from her early days as a broadcaster in Lucknow. Here she meets Akhtari Bai Faizabadi, who, as a singing woman, had to use a separate entrance to the recording studio, not the one used by “respectable” people.

Every Friday I used to drive down from Barabanki to broadcast a women’s programme on All India Radio. One day, after rehearsals as I was sitting alone in the studio, Akhtari Bai suddenly walked in. Greeting me warmly with a quick salam she said, ‘Begum sahab I would like to speak with you.’

I was shocked to see her to begin with, but her second sentence had me stumped.

‘Bittan, please get me married to Ishtiaq Abbasi sahab.’

‘Ya Allah, what sort of woman is this?’ I thought, keeping my feelings to myself. I can’t recall what I said in reply but I clearly remember that she talked nonstop. Then she apologised and said, ‘What do I do Bibi, I can’t live without him.’ Then she left as abruptly as she had walked in. I finished recording, went home and narrated the entire episode to Abbas Raza. He was most amused and said, ‘Let’s call Ishtiaq Bhai and tell him he has received a proposal.’

‘I just want to see his reaction,’ I replied, laughing.

Both my father and Justice Raza were well acquainted with Ishtiaq Ahmed Abbasi’s family. Ishtiaq Bhai was married to Asha Begum, whose father, Mateen-us-Zaman sahab was Special Advisor to Nawab Sultan Jahan Begum in Bhopal. Asha Begum had passed away two years back. My husband and I had known Ishtiaq bhai for decades. He was an extremely interesting person with a great personality. Whenever he was at a social gathering, he became its very life. We invited Ishtiaq bhai to our place for tea. He entered in his usual jolly manner, narrating jokes, calling out to the kids and then came and sat in the drawing room. Tea was served. When he was sitting comfortably enjoying his cake and pastry I said, ‘Ishtiaq Bhai we have called you for something specific.’

‘Hahn Bittan, is there something I can do for you? Tell me quickly… what is it?’

‘You should marry Akhtari,’ I said without any warning. ‘Ayyn…? What? What did you say…? Saeed bete… have you tried this cake? Come here, come to me… let us play Akhtu-Bakhtu.’ Saeed immediately jumped into Ishtiaq Bhai’s lap. Ishtiaq Bhai held his tiny hands and began to recite a local Indo-Muslim poem (like Incy Wincy Spider) about two friends named Akhtu and Bakhtu. (It was all the more amusing since Akhtu sounded similar to Akhtari!)

‘Akhtu ne pakayee badiyaan, Bakhtu ne pakayee daal,

Akhtu ki badiyaan jal gayeen, Bakhtu ka bura haal,

Sayyan phir bhi ladenge, Sayyan phir bhi ladenge.’

Akhtu fried some fritters, Bakhtu made lentil soup,

Akhtu’s fritters got burnt, Bakhtu didn’t know what to do

The two kept fighting, the two kept fighting.

He had smoothly skirted the issue. But I was not one to let go that easily. When he was about to leave, I once again repeated my sentence. ‘Hahn Hahn, achcha achca, yes, yes, we will see. I have some work Bittan, I must leave now.’

I couldn’t understand his reaction. I had mustered up quite a bit of courage to ask him directly to marry Akhtari. I stated it as candidly as possible, without beating about the bush. I was a bit apprehensive, after all he may get offended, may even turn around and say, ‘how dare you… etc etc.’ But instead I got this feeling that he was somewhat flustered and wanted to avoid the topic.

Now what started to happen was that every Friday, after the ladies programme, Akhtari Bai would come to the studio to meet me. Since, for me, she was already someone to look up to, I felt quite elated seeing her. Gradually she started opening up with me. She told me the story of her life and how she hated the profession of a courtesan.

‘My mother left me to live as a “keep” in some rich man’s house. That’s how it all started. I was very young. I couldn’t rebel. Then somehow, after a lot of dificulty I managed to get out of there. Now I am in Nawab sahab Rampur’s court, but I am constantly restless, and keep trying to figure out how to run away from here. I adore Ishtiaq miyan. Only you can help me now.’

I believed every single word she uttered, blindly. In my mind, the picture I drew was that she is a victim of her circumstances. Sick of the world she is living in, she is desperate to lead a respectable life. I should definitely try to help her. I convinced my mother and mother-in-law that Akhtari was actually very decent. Both of these ladies had been brought-up in an extremely protected and traditional environment. They were amazed to hear about the life of a courtesan and all its complexities. One day I suggested, ‘You should also meet Akhtari.’

‘Ayy nahi dulhan, I don’t think we should, we keep purdah from prostitutes,’ my mother-in-law said.

‘But she is not a prostitute, Chachijaan,’ I replied. ‘Despite staying in that environment, she is still so pure. If you all meet her, it will have a positive influence on her, the respectability in her character will emerge.’

A few days later once again I asked them, ‘Should I call Akhtari to meet with you?’

Neither responded. They changed the subject.

During this time, one day Akhtari said to me, ‘Why don’t you and Abbas Raza miyan come for dinner to my place?’ I said I would ask Raza sahab and get back to her. When I went home and told Abban, he grew thoughtful. To go to a courtesan’s brothel, and that too with his wife was unheard of. It was considered a dishonourable thing to do. Abban had never gone to a brothel by himself before. Thus far he had led a chaste life though he thoroughly enjoyed reading good books, listening to poetry, music and qawaali. Whenever he got the opportunity he gladly attended such functions.

I used to discuss everything that happened with Akhtari, with Abban. He was a simple gullible man. I had presented her case to my entire family in such a convincing manner that my mother and mother-in-law almost agreed to meet her. Abban also started enjoying listening to the stories I told him about Akhtari. In fact sometimes he would even ask about her. Now when I said she has called us for dinner, despite being uncomfortable with the idea, he agreed. And so it was that one fine day the two of us went to Akhtari Bai’s kotha.

The floor was spread wall-to-wall with the finest of Iranian carpets, gautakiyas placed here and there across them. While welcoming us Akhtari almost flew towards us in delight. Her mother was also there. After making some small talk, a table cloth was spread on the floor and food was served. It was sumptuous and delicious. Akhtari was making interesting conversation but with a conscious effort at remaining respectful.

God knows what my poor husband was going through. This was the first time he was speaking with a courtesan. Abban was well-versed in the intricacies of sher-o-shayyari poetry and was quite passionate about music. Both of them talked about these subjects endlessly. Words of some thumri were hummed. Then Akhtari gently asked, ‘Raza miyan do you not like my songs?’

‘Nahi bhai, no, no, it’s not like that, I like your singing a lot,’ Raza miyan replied, startled at being asked such a straightforward question. ‘Then just give the order… I’ll come any evening and sing at your place.’

‘Basar-o-chashm’ Abban replied. ‘Your wish is my command. I will let you know which evening you will have to take the trouble to visit our home.’