Modernism by Other Means is the first book-length consideration of the output of the films of Amit Dutta, renowned as 'one of the most foremost filmmakers working in experimental cinema today'. Each of the nineteen chapters is a close-grained, elaborate critical analysis mounted by the acclaimed film-critic Srikanth Srinivasan. Srinivasan examines Dutta’s works as a quest for modernism, one that diverges from Eurocentric rites of passage, emerging out of a collage of subjects and themes: art, history, memory, cinema, space, philosophy, civilisation. With a deep understanding of aesthetics, Srinivasan presents in this first monograph of his, a foundational intimate portrait of an artist in the broader landscape of contemporary filmmaking in India.

Following is an excerpt from the book.

Nainsukh marks the beginning of Dutta’s search for a new personal style, free of earlier cinematic influences and technical preoccupations. To besure, the film does not mark a total rupture for Dutta, and it has a definite continuity with Man’s Woman and Other Stories.There is the same emphasis onelements of nature as in the previous film. Characters’ relation to their surroundings—natural and manmade—continues to be at the focal point. Like inMan’s Woman, the men in Nainsukh are dwarfed by the cavernous architecture they inhabit.Windows remain important sites where social transactions takeplace. Spaces are still described using repetition and opposition of actor movement. However, there is a more sustained approach to the division of space acrossshots. The sequence describing Zorawar Singh’s death, for example, is a self-contained aesthetic object displaying a unique dramatic progression and formalharmony. Clocking just under two minutes, it consists of eight shots portraying the death of Zorawar, the ascent of Balwant, and Nainsukh’s reconfiguredallegiance. The economy of expression here is matched by several internal rhymes and counterpoints, providing the sequence a flourish worthy of its central position in the film’s timeline.

Nainsukh additionally features aspects fairly new to Dutta’s cinema; the focus on creative process, for instance. We see Nainsukh at workthroughout the film, working on underdrawings, making sketches from nature, surrounding himself with mirrors to draw portraits. This fascination withprocess and with the patient physical labour involved in artmaking will become a staple of the filmmaker’s later work. Then there is the interactionbetween cinema and the other fine arts that the film initiates. The bulk of Dutta’s filmography envisions a cinema that is in harmony with its ancestral arts,and Nainsukh, in its confluence of music, dance, architecture, and painting, does just that. In some ways, it recalls Mani Kaul’s Siddheshwari (1989), anotherhighly-stylized biography of an artist that seeks to set the fine arts in conversation. Both Kaul’s and Dutta’s films dispense with conventional realist expositionand, instead, look deeper into their respective subjects’ life and work for formal inspiration.They both find their shape through close attention to indigenous forms: Hindustani music and Pahari miniatures.

Engagement with Pahari miniature painting reinvigorates Dutta’s filmmaking in innumerable ways. For one, it provides him with a pool of knowledgevastly different from the one furnished by personal mythology in his earlier work. It renovates the scrapbook of imagery he draws inspiration from.The austerity of colour, contour, and field in Nainsukh’s paintings finds a correspondence with the minimalism of expression in the film. This formalsobriety is in direct contrast to the flamboyance of the filmmaker’s student projects. The absence of linear perspective, the impartial attention to figure andground, the avoidance of shadows and dramatic lighting, and the use of opposed character movement are elements common both to miniature paintings andNainsukh.The gliding camera in Dutta’s cinema is, moreover, comparable to the superposition of perspectives that characterize Pahari paintings.Numerous shots in Nainsukh contain a flat background over which actions take place, quite like in the miniatures. Triptych compositions and doubleframing abound in Dutta’s imagery, as they do in the pictures.

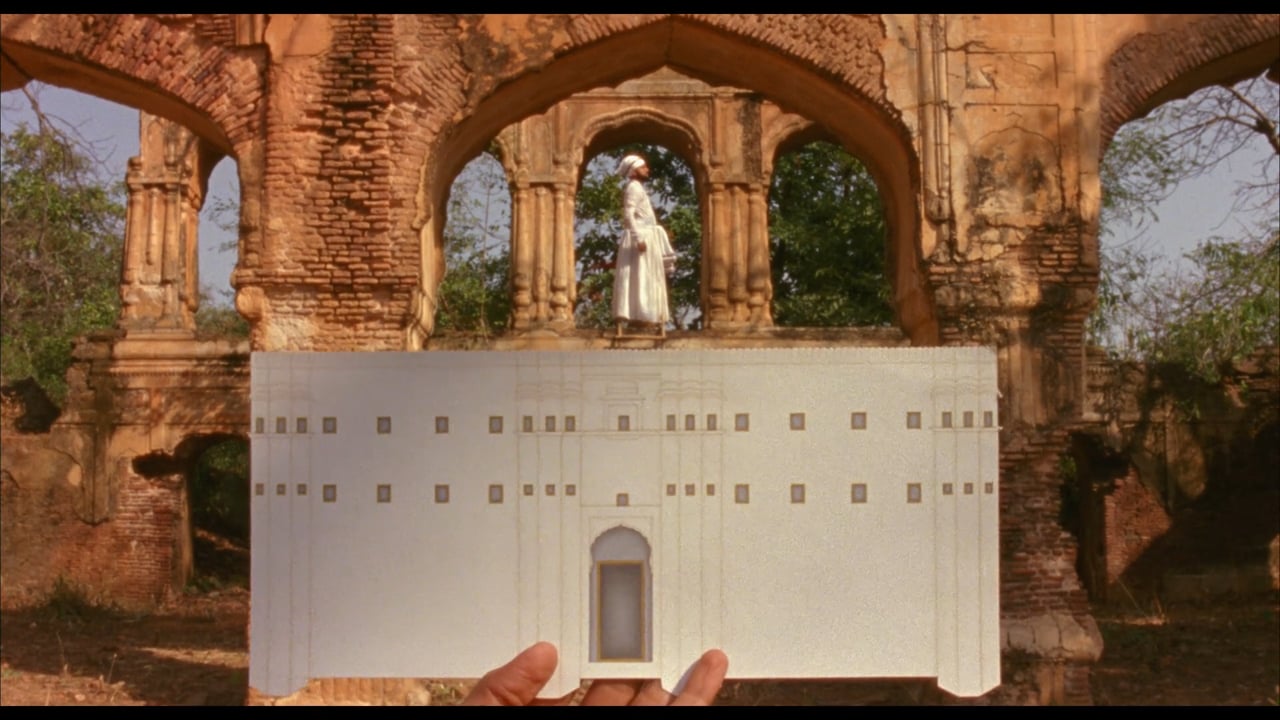

The most productive aspect of Dutta’s involvement in miniature painting, however, is the tension between flatness and depth it brings out. Thefilmmaker’s early work is rife with shots that underline the Z-axis. As in early 3-D movies, characters tend their hands towards the camera in transaction,inviting the audience, as it were,to respond in kind.The interest in paintings, on the other hand,seems to have brought to Dutta’s cinema an emphasis on two-dimensionality.In one scene in Nainsukh, the burning down of a fort is depicted by the burning of a drawing of the fort. All through, the filmmaker cuts betweenphotographed and painted images, collapsing deep space onto the surface of a painting or exploding the picture plane into real spaces. Vast stretches oflandscape are filmed in long shots without the horizon, lending them a two-dimensional quality. Characters often move laterally in front of buildings, withfaces in profile, quite like in miniatures. Outdoor shots, photographed with telephoto lenses, appear flat, while interior shots, employing wide-angled ones, give the impression of great volume. In several sequences, paintings and photographic shots take turns leading each other. This pas dedeux between two- and three-dimensionality of images is a constant in the filmmaker’s body of work, as is the one between movement and stillness.

Dutta’s aesthetic is equally informed by B.N. Goswamy’s writings on the topic of Pahari painting.The manner in which Goswamy isolates sections ofpaintings for comment translates, in Dutta’s films, to a fragmentation of images where shards of a scene are presented to the audience before the whole. Forexample,the filmmaker unveils smaller portions of the tableaux vivants in Nainsukh prior to cutting back to the entire composition. Goswamy’s remarks onthe use of time—duplication of painted figures as representation of multiple timelines—could equally apply to Dutta’s superimposition of two timelines in thefilm: Nainsukh’s period story and the present ruins at Jasrota.The filmmaker enlivens the paintings with a rich sound mix that complements the action, justlike how the professor embellishes them with his colourful descriptions. Besides, Nainsukh, born of decades of research by Fischer and Goswamy, ispatently a work of art history, visualizing a historical narrative pieced together over the years. Like the miniatures the painter views at the end,it develops anaccount of court life in Jasrota under Balwant Singh through the physical traces the period has left behind.

Finally, Nainsukh crystallizes moments of historical valence, ideas that have implications beyond the scope of a biography. It trains its eye not just on theGuler master’s history, but on his place in history. Specifically, Dutta’s film casts light on the social position of the painter in eighteenth-century feudal India.Nainsukh was not only the painter in Balwant Singh’s court, but also its impresario. He would arrange dance and music performances for the king’s pleasure.In one of the many triptychs in the film, he stands by his patron’s side, commenting on the musical concert taking place. He is often seen with the otherlabourers of the royal retinue. Nainsukh has little of the elevated social status that his European counterparts had. He is one among many vassals in Balwant’s entourage. That is why the scene where the dying king returns all his paintings to the artist is of epochal significance. Like the Sun King in Albert Serra’s The Death of Louis XIV (2016), whose protracted demise enacts the power struggles overarching theEnlightenment project, Balwant acts out a historical transformation through his final gesture, bequeathing art historical legacy from the line of patrons tothose of artists. In his passing, he frees Nainsukh of all feudatory obligation, effectively ushering in a nascent modernity. What Nainsukh experiences,viewing his own paintings one by one, is the blossoming of an aesthetic self-consciousness, the notion of the artist as creator as opposed to the artist asmessenger. These paintings narrate Balwant Singh’s life, sure, but they also chronicle Nainsukh’s own artistic development. In transplanting art’s primaryfunction from the public realm to the private, the last scene of Nainsukh inaugurates the story of modern Indian art, the subject of two of Dutta’s subsequentfeatures.