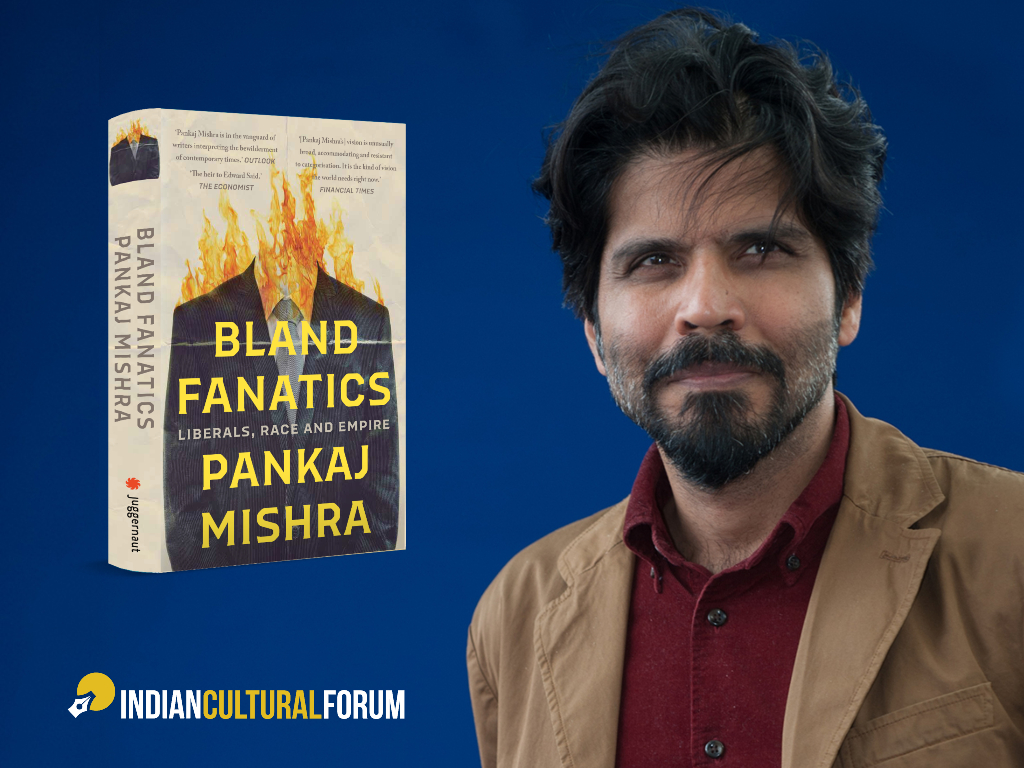

In Bland Fanatics: Liberals, Race and Empire, Pankaj Mishra examines a range of opportunistic appropriations of and attacks on liberalism, particularly from the late twentieth century onwards, along with the political shapes into which liberal thinking has bent itself in its association with global powerbroking.

In this conversation with Salim Yusufji, he talks about socio-political movements around the world, liberalism, political manipulation on digital platforms and more.

Salim Yusufji (SY): Do you distinguish between two kinds of identity-based political movements worldwide: the status-quoist majoritarian ones that are dead against universalism, and those based on Enlightenment values, arguing for a truer universalisation of rights? The latter are also identitarian in cast, but with an agenda of greater inclusiveness. Where would you stand these movements — of women, dalits, ethnic minorities, indigenous people, sexual minorities — in relation to the Modis, Putins and Orbáns of the world?

Pankaj Mishra (PM): I would argue that what you call identity movements — that is, movements of women and minorities — are actually movements for social justice and rights, and that it is a mistake, often deliberately made by their detractors, to call them identity-based movements — easier to belittle or dismiss them, or insist on a deceptively vague “common good,” when they are presented as a form of identity politics. I would also argue that the universalisation of rights is not a strictly Enlightenment value — many of the leading figures, Voltaire or Kant or Hume had only contempt for the rights of blacks, native Americans and women. I think we need to stop reflexively invoking the Enlightenment in this way, and learn to draw upon other resources in the fight against injustice and cruelty.

You are of course right that majoritarian figures and parties seek to build large platforms by offering an identity built around hatred and marginalisation of minorities; they have little interest in substantive questions of justice.

SY: How would you respond to the view that liberalism is a mere stalking horse to fascists and authoritarians worldwide? When Putin and Duda claim to fight anti-national liberals, it is the gay community and feminists they go after. Muslims in India are hardly at the vanguard of the international liberal order, but they are the real target of the Sangh parivar. Those whom Trump calls “leftist radicals” are often enough members of marginalised communities. We see this in the growing numbers of political prisoners in India. A Nehruvian elite forms no part of their numbers.

PM: Yes, for many demagogues and their followers, the word “liberal” and “liberalism” are a kind of shorthand for the old elite — Nehruvians in India, Kemalists in Turkey, East Coast and West Coast metropolitans in the US, BBC-watching, Guardian-reading Londoners, pro-American free-market reformers in Poland, and so on. They may have lost political power but these old elites still wield intellectual and cultural power, hence the great loathing of them among majoritarian far-right movements. At the same time, this loathing finds easier and more vulnerable targets among ethnic and sexual minorities (who are often seen as under the protection of, or being “pampered” by, the “liberals”).

Also read | On Ta-Nehisi Coates

SY: Would you say the twentieth century’s leading liberal thinkers failed to imagine a shared habitation of ideas? Isaiah Berlin, for instance, regularly viewed ideas in the context of personal biography. Both he and Karl Popper saw the individual as the true agent and object of political ideas. They measured the health of a political system in terms of the individual liberty it afforded. They were responding to the totalitarian character of communist governments, and were suspicious of any talk on behalf of “the people”, but do you think they discounted oppression as a collective experience and source of collective ideas? Berlin did make an exception for Jewish people and Israel, but it stands out as an exception.

PM: Coincidentally, I have been writing about how both Berlin and John Rawls failed to consider the implications of liberty and justice for the newly independent nations of Asia and Africa — and they were theorising about these ideals precisely during the most hectic period of decolonisation. Surely, self-determination and nation-building offered a case of positive liberty. But, as you say, Berlin was interested in this subject only in so far as it intersected with his Zionism. I think cold war liberalism was an incredibly parochial and self-regarding intellectual culture. One reason why it has little to say to us today is that it failed to acknowledge, let alone discuss, the ambiguous experience of modernity in most of the world, which called for a radical re-configuration of most of the political concepts drawn from the experience of imperialist nations like Britain and America.

SY: Timothy Snyder contrasts the

PM: I am not sure what Snyder means by this. I have not read his book.

SY: Your essay on Jordan Peterson looks at his writing, while noting that he is still more of a presence in the digital world. In India, there is mounting evidence of political manipulation on digital platforms, but there is also a view that these platforms are the true bahujan media, successful in bypassing the savarna filters of traditional media operations. How would you characterise the digital space?

PM: I think the mainstream media everywhere is to largely blame for ceding its moral and intellectual authority to digital media. If it had been self-critical enough, accommodating of people from other classes and castes, and not such a protection racket for the privileged, it wouldn’t have faced this destructive crisis of legitimacy.