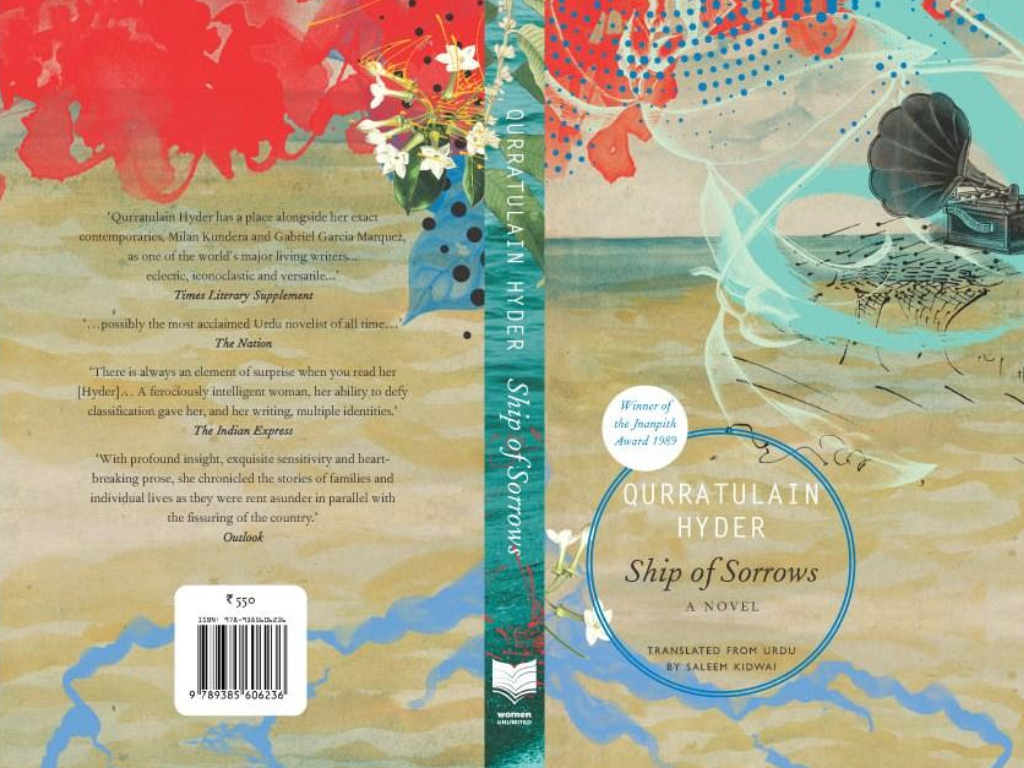

Safina-e gham-e dil (1952), Qurratulain Hyder’s second novel, takes its title from a line in Faiz’s nazm “Subah-e azadi”. Translated as Ship of Sorrows by Saleem Kidwai, the story vividly recaptures a young woman’s growth into adulthood and political disillusionment at the time of Partition.

The fifty-eight brief chapters function as vignettes, leading us through an upper-class social milieu, the world of Awadh and the United Provinces, a world then recently lost to Hyder who had moved to Pakistan. The large cast of characters includes real-life figures, such as Attia Hosein, Mridula Sarabhai, Rehana Tayyabji, the sisters Uzra Butt and Zohra Segal, and Azuri – the dancing siren of Bombay cinema – as also portraits of Hyder’s parents, with intermittent appearances by the writer, speaking in the first person.

In English, Ship of Sorrows appears as a distinctive addition to landmark works from this period, such as Attia Hosein’s Sunlight on a Broken Column and Mumtaz Shah Nawaz’s The Heart Divided.

The following is an extract from the book.

At the All India Women’s Conference session that day, Fawad’s mother, Begum Nasim Ahmad, had had some crucial decisions approved. The day had been hectic, and a few busier days lay ahead. Women delegates from Maharashtra, Madras, Bengal, and Hyderabad (Deccan) were in town. Lady Kailash Srivastava and Mrs. Lakshmi Menon, MLA and MLC, were hosting the delegates the following Sunday, and Begum Nasim Ahmad was busy with many phone calls and letters in that connection. She also had to interview a new tutor for her ward, Rahil, and after discussions with a few female and male educationists, decide what she should study the next term.

Begum Nasim Ahmad, Rani Balbir Singh, my aunt Mrs. Saumeshwari Rajvansh and my mother were representatives of a group that had learnt to be formally embarrassed about being feudal and degenerate, and yet were conceited about it. Following the movement initiated by Sir Sayyid, exalted Allah had instilled a genuine urge for social and national reform in their hearts. Apart from arranging ladies’ conferences along the lines of One Hundred and One Nights fantasies, they had played an extraordinary role in writing and promoting Urdu literature over the last thirty or thirty-five years. Their poems, novels, and essays were so powerful that they often confounded conservative men. At the age of fourteen, my Ammi had written a very progressive and instructive reformatory novel whose heroine, Akhtarunnisa Begum, had very stoically faced the oppression of a patriarchal society and emerged victorious. Men in Ammi’s novels were usually depicted as being deceitful, hypocritical and vulgar but the hero was angelic. Her books were a perfect reflection of her class background, which towards the end of the last century and the beginning of this one, had, like the Ottoman upper classes, begun adopting western ways. The girls were in purdah, but English governesses taught them English and how to play the piano. Ammi, before her marriage, wore gowns that were fashionable in the Edwardian era, and sat in her father’s over-decorated drawing room, writing letters to her other cultured peers. Ze Khe Sheen1 was part of this world. So was Akbar Allahabadi. But after the First World War, other pastimes and challenges made their appearance, such as the nationalist and non-cooperation movements, and so these ladies gave up their farshi pyjamas and banarsi saris and began wearing khadi, although even with khadi, the latest fads and fashions were kept in mind. Ammi not only started wearing khadi herself but also had khadi frocks made for our governess, Miss Kathleen Chew. Lucknow, Aligarh, Delhi, and Hyderabad in the Deccan were centres of activity. Thirty years ago, it was these women who had taken the lead in giving up purdah. The Hindu-Muslim conflict hadn’t arisen then. Political dilemmas and hate are the result of daily struggles and economic issues. Rani Balbir Singh, Lady Srivastava, and Begum Nasim Ahmad may have faced personal problems in their lives, but the upper classes were protected from these conflicts—there was complete peace and reconciliation.

All the women had different and diverse interests. Apart from literature and politics, Ammi was acknowledged for her matchmaking skills. Saumeshwari Mausi, after returning from the club (where a couple of times, she had closed her eyes, muttered Ram Ram, and tasted liquor), would pray regularly. She was a spiritual being, and would close her eyes and listen to qawwalis and eulogies to the Prophet with the same devotion with which she listened to bhajans. No one was better at resolving marital conflicts than Begum Nasim Ahmad, while Rani Balbir Singh was equally skilled at creating them! Lady Mitra had once entered the busy Roshan Ara Club and beaten up a colonel who lied to his wife and was dancing with an English lady. Politically, they all were extremely anti-men; that is, all men are oppressive; Hindu women should have the right to divorce; divorce should be easier for Muslim women; why were they deprived of their inheritance in Punjab; etc. etc. However, in real life, there couldn’t have been more obedient wives than them.

While writing her letters, Begum Nasim Ahmad realised that the tailor had not delivered Rahil’s coat and skirt, that the cook had again cheated in the purchase of meat, and that the miserable Tammu had still not refreshed the Khan Bahadur’s huqqa. She immediately set aside the All India Women’s Conference and rushed to the kitchen.

1. The poet, Zahida Khatoon Shervaniya (1894-1922), who published poetry using only her initials Ze Khe Sheen (Z.K.S.).