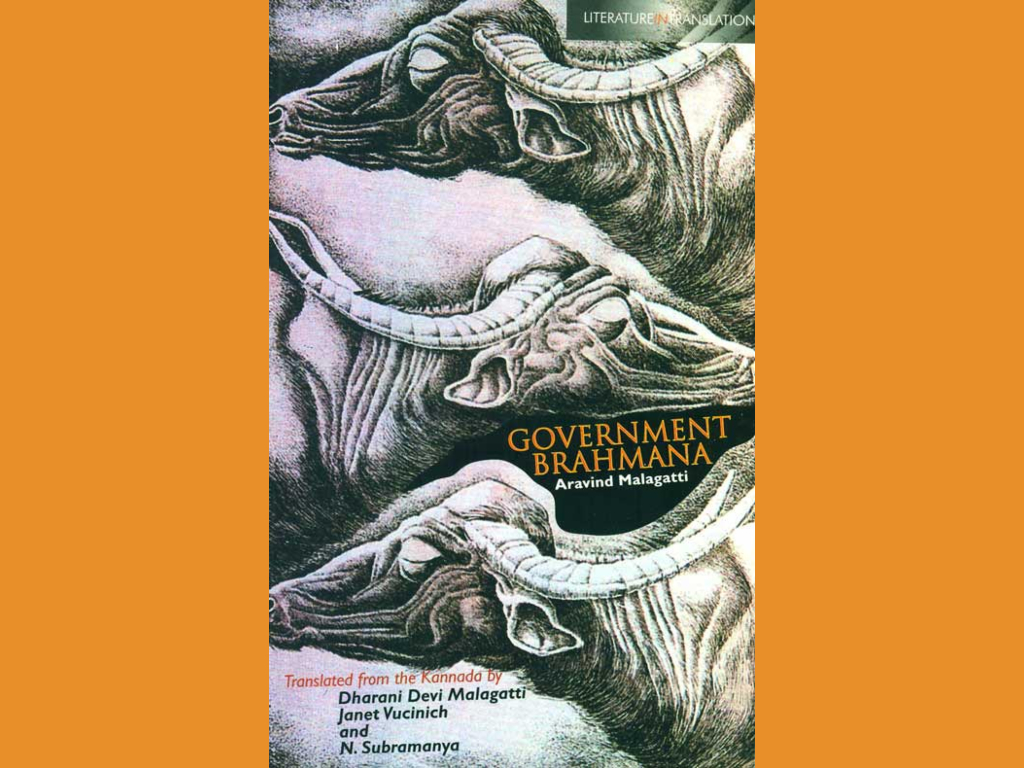

Translated into English by Dharani Devi Malagatti, Janet Vucinich and N Subramanya, Government Brahmana is the autobiography of renowned Kannada writer and scholar, Aravind Malagatti. The autobiographical narrative is written in the form of a series of episodes from the author’s childhood and youth and is also the first dalit autobiography published in Kannada. In each of these episodes, Malagatti reflects upon specific instances from his childhood and student days that illustrate the normative cruelty practiced by caste Hindu society on dalits.

The following is one such episode titled “An Eastman colour movie called Okuli” from the book.

There are interesting equations between the traditions of the village and the traditions of the untouchables’ colony. These equations work to the detriment of dalits and to the advantage of others. In the guise of having given a role to the dalits in the affairs of the village, they put their lives in a fix – like areca nuts placed between the twin blades of a cutter – and slice them up. Just as they are recruited in the present democratic set up for the lowliest jobs, earlier they were recruited for traditional menial jobs. I wish to narrate one such disturbing tradition here.

It is a custom that the Okuli festival should be celebrated every year in Shravana, the fifth month of the Hindu calendar, which generally falls during August–September.

The women of our colony had mixed feelings about Okuli— some felt elated while the others did not. The Okuli of Bidarakundi was famous in the surrounding area. And those who took part in it were none other than our womenfolk.

The tradition went like this: dalit women had to remove their blouses and wear andugachche, a lower garment worn above the kneecaps, hemmed tightly and tucked into the waist band. A sari was worn to cover the waist and the loose end of it was used to cover the head. The women had to hold several long branches of the lakky tree. These branches were three to three and a half feet long, and thin and flexible at the tip. Standing opposite these women were non-dalit and non-brahmin men, who also wore andugachches and had a big sack waterproofed with sticky raala and sere on their shoulders. This group usually comprised the notorious elements of the village.

Okuli is not in fashion in places that are civilised. But numerous decrepit pits can still be seen around the temples in our villages. These stand as witnesses to the past glories of Okuli. The men filled their sacks with yellow- and red-coloured water (a mixture of turmeric and vermilion powder) and splashed it with force on the women. The women were expected to dodge and beat up the men with the long canes they held in their hands. This was sort of a traditional sport.

As the men splashed coloured water on the women repeatedly, the women chased them to take revenge, not bothering about their wet bodies and the loose end of their sari falling down from their heads. Their wet bodies, breasts and thighs—all bared to give free entertainment to the lecherous audience and the lustful players. The red and yellow shades of colour that splashed on the women’s bodies time and again gave the scene the effect of an Eastman colour movie.

Okuli had to be celebrated every year. Otherwise, it was assumed there would be no rain—crops would be infested with pests and the village would be plagued by diseases and Shani. The dalit men and women who feared these superstitions, would fall prey to them in the name of tradition.

My aayi, a well-built woman, would take all of us – me and my brothers – to the fair every year; not for the celebrations, but the meals. Of course, she would let us see the celebrations without fail. When we could not see, she would lift us onto her shoulders or would make us stand on any wall nearby.

When I came to Dharwad for my higher education, I used to accompany a friend who was doing his Ph.D. on his fieldwork. Once, in some context, I narrated this tradition to him. He then brought to my notice something nastier that took place in a village neighbouring his. I decided to go and watch it. It was a game that took place in the auspicious month of Shravana just like Okuli. Even here, dalit women were necessary, and the game was held in front of Hanumantha, the bachelor god.

In this game, both the male and the female had to be nude, and had to dance together. Following which, the female had to sit on the male’s shoulders, peel a plantain and put it into his mouth. When the male tried to bite it, she had to pull it away. Finally she too would not eat the plantain but only lick it. The licked plantain would then be eaten up by the upper caste male. This was a significant aspect of this tradition.

When my friend described this tradition, I expressed my wish to write an essay about it. He too took a keen interest and collected some more information for me regarding the tradition. The villagers informed us about the specific day on which the celebrations would take place. When we started for the village the next day, we came to know that the event had already taken place the previous night. Because this tradition was attracting too much attention from outsiders, they had decided to perform it without letting others know about it. I do not know if this tradition exists in Dharwad district even now. It seems this village was once called Thunnaganooru—The village of testis. Despite being a folklore scholar, I could not bring myself to write about it, because I felt such topics had only become means for scholars to show off their expertise. Folklore scholars had concentrated only on the symbolic aspect of such traditions, blocking their minds to superstitions and social evils. I was fed up with symbolism and exaggerated scholarly remarks: ‘“Feeding the plantain” is a“fertility cult”’; ‘“Okuli” signifies plenty’; ‘Turmeric and vermilion powders stand for something else’; and so on and so forth. I was disgusted and gave up writing about it.

The reason for narrating all this to you is to say that the clothes (sari–blouse) given as gifts to dalit women by upper caste people once a year have lured the former. Around my native place such traditions still exist. I have heard that they have changed just so much as to allow the women to cover their breasts with kuppasa. Note that in an environment brimming with traditions such as Okuli, I had to pursue my education. While it shows how every small occurrence in society can act as a hurdle to an aspiring individual, it also highlights the situation of dalit women. When you notice how these men – who strip the women off their honour and turn them into prostitutes for their lustful needs – invent ways of protecting their self-esteem, you do feel like asking, ‘But don’t these women have self-respect?’ These men, who watch the Eastman colour movie of Okuli in the name of tradition, get wild when asked, ‘But will you allow you wives to stand in public like this and play Okuli?’ When will they ever realise that these women too possess dignity, like their wives? What should be said about scholars who, with the sole aim of exhibiting their expertise, glorify such disgusting traditions using high-sounding words and raise such traditions to positions of great honour?

There are some disgusting traditions in Savadatti,1 like bevina uduge where only neem leaves are worn around the waist, and gandhada uduge, which has nothing to do with sandalwood as the name suggests, but means wearing neem sticks devoid of leaves around the waist. There is even the tradition of bettale seve, which demands celebrations in the nude.

Isn’t it funny that such superstitions, instead of getting obliterated with the passage of time, are instead reappearing in new forms?

More recently, in Karnataka, they have been successfully holding programmes of ‘feeding shit to the dalits’. Don’t they qualify for the Guinness records in human cruelty? We are so sensitive that we shy away from referring to such incidents in plain words. Instead we use phrases like ‘mala prashana’ or ‘ameedhya prashana’ to connote ‘feeding shit’, as though it were a sacred act of worship.2 If such is our aversion, then imagine the plight of those who have actually been forced to eat shit?

1. Goddess Yellamma is the presiding deity in Savadatti. The nude worship practised there has received wide media attention and criticism. There have been attempts to put an end to such traditions. Similar traditions are prevalent in other places, only they are in different forms.

2. Mala prashana and ameedhya prashana mean the same thing—‘feeding shit’. But the words are derived from Sanskrit.