At the time of writing this story, there are 1,028 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Dharavi, one of Asia’s largest slums in Mumbai. There have been 40 deaths from the area as of now, and almost 2,500 persons from Dharavi have been kept in quarantine. The numbers have been increasing on a daily basis and it has been a matter of serious concern for the health department of Maharashtra.

Dr. Kailas Gaud is a practicing doctor in Dharavi with a Bachelors of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery degree. He has been tending to patients in the area for decades. Dr. Gaud is also a social activist and was a member of the Maharashtra State Backward Class Commission. These days, Dr. Gaud opens his clinic once a day. “I am still treating almost fifty patients per day from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m. Patients complain of a running nose, a slight fever and issues related to breathing. They are scared right now and that is making them nervous,” said Dr. Gaud.

There are 300 such doctors in Dharavi. On the assumption that each doctor is visited by at least 30 patients per day, (as per Dr Gaud it is almost 40 patients per day) around 9,000 persons are visiting doctors in the area on a daily basis. Dharavi, spread over an area of around 2.5 square kms, has a population of more than 8.5 lakh people, making it one of the densest human habitats in the world.

Dharavi is not just a slum. It is also a manufacturing hub for a number of items ranging from garments to plastic to sweets. The area provides employment to almost 6 lakh labourers, the majority of them migrants. With a lockdown in place, they are jobless and no work means no money and no food for these daily wagers. It is the biggest challenge before them at the moment.

Twenty-four-year-old Niyaz Shaikh hails from Banda in Uttar Pradesh and has been staying in Dharavi for the last six years. Niyaz works as a tailor in a jeans factory which has been closed since March 22, the day Maharashtra announced a lockdown. For the last month, Niyaz has been surviving on the food provided by either the Brirhanmumbai Municipal Commission (BMC) or various NGOs and social organisations.

“Our factory owner gave us half of April’s salary. We could only survive on it till April 15. Since then, we have no food. We go out on the road everyday and get food being distributed by the government or some people,” said Niyaz. He does not blame the factory’s owner either. “We can see that the factory is closed and the owner is also faced with trouble. At least he gives us space to sleep in the factory, that too free of cost. How can we blame him?” asked Niyaz.

There are literally thousands like Niyaz who are struggling to meet their needs for the day. Pratham, an NGO known for its work in education, is one of the many NGOs which are providing all possible help to the people of Dharavi. Prafull Shinde of Pratham is coordinating the relief effort. “We are now providing 300 food packets daily. Initially, we were providing 500 food packets but now many organisations have come forward to help those in Dharavi. We are now focussing on giving people grains and other ration so that the really needy families can cook at home,” said Shinde.

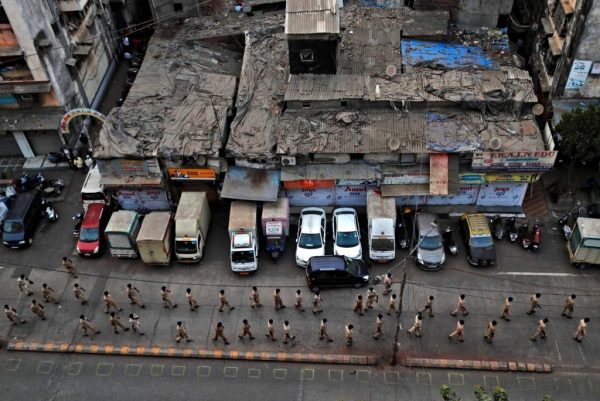

As they are going hungry and are in need of food, the people are coming out on the streets. They are looking out for vehicles of NGOs or the BMC for food. “This is obvious. For how many days can these people stay inside their homes? They will starve. So, we are seeing hundreds of people on the road at any given time in Dharavi. They gather at every chowk. Hence, social distancing is not possible here in Dharavi,” said Fakruddin Shaikh, a social activist from the area.

Dr Gaud believes that food distribution could be one of the reasons for the social transmission of the novel coronavirus. “We cannot expect people to stay at home when they do not have anything to eat. So, norms of physical distancing are not possible to follow in an area like Dharavi,” said Dr. Gaud.

Another reason being cited are the public toilets is rather major reason. There are 450 public toilets servicing such a huge population. Activists like Fakruddin believe that these toilets could be a major reason that people are getting affected by the coronavirus. Almost 250 persons use one public toilet, according to him. “The BMC is getting these toilets cleaned every day. We include those who have used the same public toilet as a COVID-19 patient in quarantine lists,” said Assistant Municipal Commissioner Kiran Dighavkar.

As the number of patients mount, the migrant workers and others are also growing impatient and want to leave Dharavi and Mumbai at the earliest. T. Raju Dasa is from Tamil Nadu’s Erode district. He has been living in Dharavi for the last 11 years and works in a bakery. Raju lives in a rented accommodation which he shared with six others from Tamil Nadu. But, with all of them without work and money, they want to go back to their villages. “We can not pay the rent here. We do not have money and have been surviving for the last 15 days due to food being provided by NGOs and the BMC. But now we want to go back to villages. We will return when everything goes back to normal, but there is no point staying back,” said Raju.

Train services have begun from Mumbai to many states including Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Labourers are now trying to get onto them, but not without another set of hurdles. One of Niyaz’s colleagues, Mohammad, tried to get passes from the Dharavi police station for two days, without any luck. “I am told many sit in queues from three in the morning. I went at around 8 a.m. but the line was too long. I am now trying some jugaad to go home by a truck or something like that,” said Mohammad.

The entire situation has exposed the limitations of the lockdown on many levels. The first patient of COVID-19 was found in Dharavi on April 1 and the lockdown began in Mumbai on March 22. “Everyone was saying that if the coronavirus reached the slums then there would be serious problems in controlling the spread. So, the government should have planned it well – from sending the non-affected labourers back to their villages to arranging food and testing in large numbers. It could have been done pro-actively. But that did not happen and Dharavi has become a serious issue before all of us,” said Shinde.

As of now, the government’s focus is on increasing the immunity of the people in Dharavi. The Ministry of AYUSH is promoting a number of medicines for immunity. “That should be the approach now. I would rather say that increasing immunity should have been the approach from day one. In an area like Dharavi, one will find more and more affected by COVID-19 but many of them could be asymptomatic,” said Dr. Gaud.

The lockdown cannot be a permanent fixture and these small-scale industries and labourers cannot remain without work. Normalcy needs to return but the challenge before the government will be that of planning; from increasing the immunity of the people to providing them with facilities like public toilets in adequate numbers would be necessary. Dharavi underlines it with every new case of COVID-19.