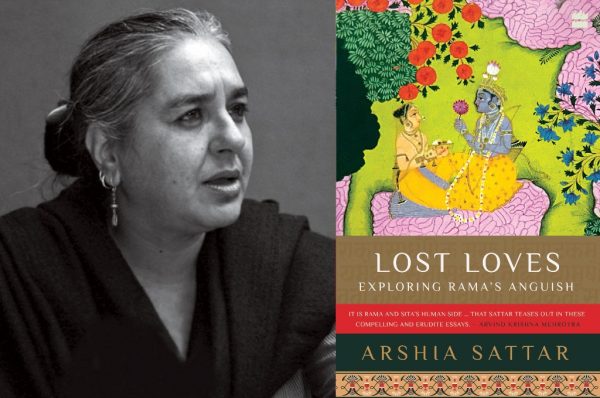

When Arshia Sattar wrote Lost Loves: Exploring Rama’s Anguish, its readers found a Rama who had not only loved but had equally lost. Renowned for her English translation of the epic Ramayana and author of several books, Sattar talks to academic and writer Ananya Vajpeyi about the “dialogue between life and literature”, Sattar’s identity as a Muslim writer and translator in an India that is dominated politically by the Hindu Right, her works and much more.

In part one of the two-part conversation between Arshia Sattar and Ananya Vajpeyi, they talk about Lost Loves; the character of Rama; the city of Ayodhya; and translating the epic Ramayana.

Ananya Vajpeyi (AV): Why did you write Lost Loves, Arshia? Was it meant to critically explore aspects of the epic, or was it a set of essays about love and loss, for which Rama’s story merely provided a particularly felicitous occasion?

Arshia Sattar (AS): This didn’t start as a book about love at all. It started as an exploration of Rama who always seemed so distant to me and from me. The text is called Ramayana and if we dismiss Rama, we are dismissing three quarters of the story. How can we claim to say anything about a text, to know it in any comprehensive way, if we ignore the character after whom it is named? I felt that especially as a feminist, I needed to know why Rama acted the way he did, in ways that made me and so many other women over the centuries and across cultures hostile to him. I wanted to understand Rama’s justifications for his actions — particularly his behaviour towards Sita. And it ended up being a book about love. You know people better in their private lives than in their public ones. How someone reacts to love is more telling about who they are than how they react to fame. Love is about being vulnerable and that’s where we’re more likely to see Rama as he is. And then, of course, it became a book about loss, because Rāma loses the love of his life. It was through this that I realised that the Ramayana is also a love story, perhaps even a cautionary tale about how devastating it can be if you place duty before all else.

AV: I genuinely believe that the boundaries between the texts we hold dear, as scholars, and the experiences we have, as human beings, are porous. That we not only learn from what we are reading, but that we become the characters we love, and that the narratives which entrance us, in some sense, shape, prefigure or alter the course of our lives. Have you found this to be true, in your engagement with Rama and the Ramayana? Do you, in uncanny and subtle ways, find yourself living the text? Or if not — if my theory strikes you as implausible — could you describe to me your particular form of immersion, identification and insight into the texts that you are most intensely engaged with?

AS: I find this theory very unsettling. Yes, of course, we pick texts and characters that suit our temperaments and our interests, but the cause and effect that you’re suggesting is rather too deterministic for me — even though I study the most over-determined of all texts.

Immersion is really very simple: read read read and when you think you’re done, read some more. Read the text you’re working on, read every translation you can, read other texts from the same period, read other versions of the same story, nothing is too trivial or too profound. And read because you cannot write without reading. Listen to other people talk about the text. You may disagree but you’ll always learn something new. Personally, I’m not one for identifying with the text, the voice, the characters. Maybe that’s because my text is 2000 years old. I can feel empathy and sympathy, I can try and relate emotions and events to the world that I live in, but I think distance is important. Otherwise, you become a believer — which is fine, but it’s not for me.

The most beautiful version of immersing oneself in a literary text that I’ve read recently is in Amitabha Bagchi’s Half the Night is Gone in which a young man leaves his wife and dedicates himself to studying the Manas. I’m sure kathakars and pathaks and other kinds of scholars who are also believers have this privilege, but this is not my privilege. As far as insights go, anyone can have them. An insight is a flash of intuition and that can come as much from a first reading as it can from a lifetime’s study.

Also Read | On translating Valmiki’s Ramayana: ICF in conversation with Arshia Sattar

AV: A very fundamental question, it seems to me, that springs from the Ramayana: How is the patently flawed personhood of Rama superseded and supplanted by the undying image of his perfection? Why do readers over centuries see him make mistake after mistake, suffer loss after loss, and yet insist that he is the closest that a mortal ever comes to divinity in the whole world and all of time? What is the secret of this alchemy that transforms a man into a god, imperfection into flawlessness?

AS: Let’s be clear about this — over the centuries, some people have chosen to see Rama as flawless and through the same period, the patriarchy has been profoundly invested in Rama’s perfection. And when I say patriarchy, I include the hierarchy of caste and its concomitant abominations. There have been many “corrections” to the Ramayana over the centuries, women have talked back to the story in their songs, indigenous and heterodox communities have re-made Rama in ways that are more acceptable to them, very often through criticism rather than validation. In fact, we can see each new version of the Rama story, from Kamban and Tulsi to Jain Ramayanas, Periyar, Samhita Arni, as attempts to come to terms with the persistent and insidious hegemony of Rama’s perfection. Ramanujan said once in class that “an epic is like a crystal, it grows where there is a flaw.” I think the Ramayana story is alive and well today precisely because we’re still trying to figure it out, we’re trying to make sense of Rama, rather than accepting the fact that he is perfect.

AV: Is the story of Rama and Sita the greatest love story ever? If so, could that be because it is marked again and again by estrangement, exile, misunderstanding, betrayal, doubt and ultimately, loss? Can a true love-story actually end with a “happily ever after”? Or is it precisely love unrequited, unconsummated, remembered, forgotten, deferred and abandoned that keeps us interested in the entanglements and adventures of lovers like Rama and Sita?

AS: I don’t know about the greatest love story ever, we all have our favourites. Mine is actually Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. I still sob loudly when I read it and I do still read it, but with great trepidation and caution. Besides, the Ramayana is more than just a love story, unlike Romeo and Juliet, or Heer Ranjha or Shireen Farhad. Ramayana is overtly a story about many other things as well as love — kingship, dharma, family, god (if that’s your preference). But it’s certainly true that tragic love stories have a greater hold on our imaginations and our hearts than happily ever after stories, which we tend to consign to children’s reading.

Why do we love them so — perhaps because we know that in real life, even in the happiest of loves, one person will die before the other. That is tragic enough, we don’t need estrangement, exile, misunderstanding, betrayal and all the other elements that make a good story to know that our own loves will end and that they will end in sadness. There is no forever, there is no ever after. These narrative tropes exist to remind us that one of us will be left alone, bereft, never again complete. I’m sure that in every happy couple, each one begs whatever powers they believe in to let them die first. And so in that sense, there is never a happily ever after for mortals. All love stories in our real lives are tragic, even ones that end in divorce which stands for the end of love or a love that ran its course and was not meant to last an entire lifetime with the same person. That’s sad, too, a short-lived love.

Also Read | Rama’s Divinity

AV: You have written so much about Ayodhya, Rama’s capital, lost and regained, in the epic. Hardly anyone could know as much about this city as a literary symbol as you do. You have a chapter in your book on the three cities of the Ramayana — Ayodhya, Kiskindha, and Lanka — the capitals, respectively, of the human, the monkey and the demon kingdoms.

When you take the epic, say, to young people, how do you teach them to distinguish between these cities as places inside a narrative, and as “real” places in the world we inhabit — Ayodhya, site of the Ram-Janmabhumi / Babri Masjid dispute, say, or Sri Lanka, a country south of the Indian subcontinent, long torn by a civil war between Sinhalas and Tamils? How do you approach living political flashpoints like the Ram Mandir or the Ram Setu, from your vantage as an expert on the epic? What can you “do” with your classical knowledge in the contemporary classroom?

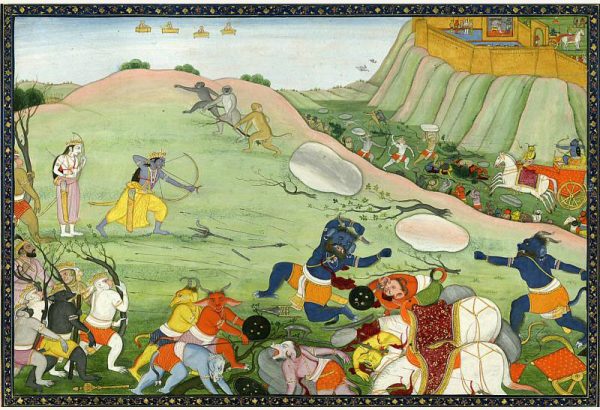

AS: There are literary truths and there are so-called historical facts and ne’er the twain shall meet, I believe. Literary truths tell us about human nature, about the human condition, about the universality of love and hate, about how different cultures answer the same fundamental questions. Literary truths are also about the imagination, about flying monkeys and rakshasas with ten heads, about daughters sacrificed so that a temperamental goddess will send favourable winds. In the Ramayana, it is true that Hanuman can fly and that he sets fire to Lanka with his burning tail. But it is not true in real life that Hanuman was an incendiary bomber pilot as was suggested in the 1930s by a dignified (no doubt) and learned brahmin gentleman.

Indian students often ask me if the Ramayana is true. And I say, it’s true in a literary sense and that’s a very important way to be true. It’s also possible that there was a prince who was exiled just before his coronation by his father’s wife and that while he was in exile, his wife was abducted by another powerful king and that he had to find allies and win her back. But that ‘true’ story is not Ramayana — Ramayana is flying monkeys who speak Sanskrit and can change their shape and form, Ramayana is ten-headed demons with twenty arms.

So, in short, I have no truck with “this is Ayodhya where Rama was born” and “that is Sri Lanka where Ravana was killed.” It’s so much more moving to have sthalapuranas all across the country that say, “Rama and Sita slept here,” “Sita dropped her jewels here” — the Ramayana has always happened in everyone’s backyard, how lovely is that!?

AV: If you could read other classical languages besides Sanskrit, which texts (epic or other) would you most like to read, say in Persian or Greek or Tamil or any other language, and why? What attracts you to a text, in other words?

AS: Funny you should ask that and mention these very languages. I feel that this could be (probably should be) my last Ramayana book. What do I do next — what text, what language? I’ve been thinking about ancient Greek because I want to read those epics and plays and myths. All the people who have influenced my reading of the Hindu epics have known the Greek texts well. They belong in the same family, our stories and theirs. I know that I will love reading the Greek texts with Ramayana and Mahabharata as my companions. There’s also Persian which is so attractive in so many ways — long narratives, poetry, history. Not to mention a language which does not gender its nouns, what a relief will that be!

What attracts me to a text — the past, definitely. I’m not interested in modern or contemporary texts as objects of study, though I read them with pleasure. Big stories are another draw as are magic, strange beings that can do things that I can’t, promises, boons and curses. The attraction of a big text is that you’re never done with it, it’s never exhausted, there’s always one more thing that you didn’t notice, one more character who suddenly waves at you and asks for attention. Complex narrative structures are always exciting, frame stories and that kind of thing. And somewhere, what draws me to a text is the possibility of translating it. No one, not even the writer, is more intimate with a text than a translator.