We must never forget the nightmare of the Covid pandemic for many reasons. To gear ourselves to endure, comprehend and overcome our broken and uncertain present. And to stir our radical imaginations in a resolve to build a better future. But before we remember, there is something else that we must first do.

And this is to grieve.

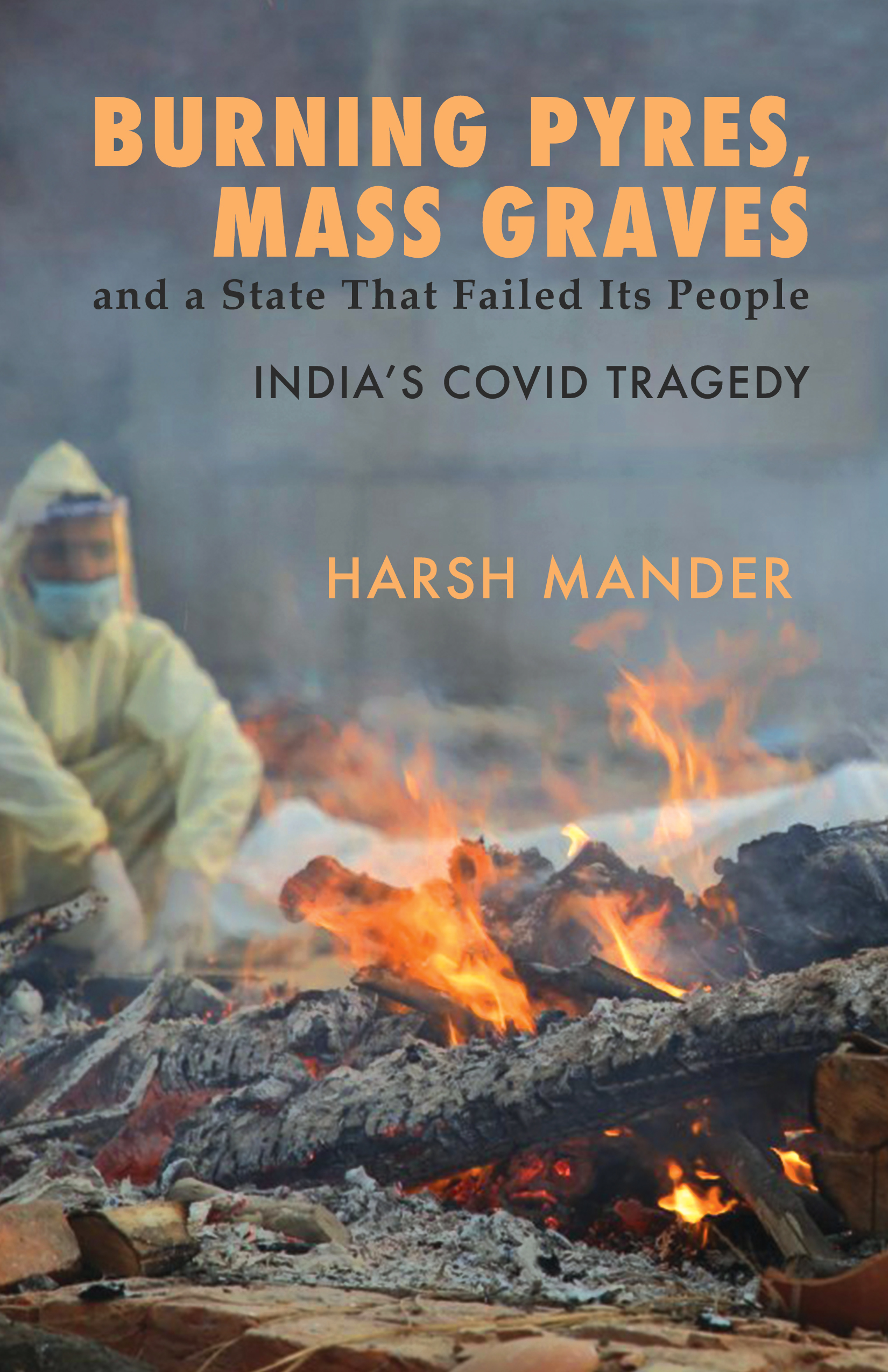

In Burning Pyres, Mass Graves, Harsh Mander presents a comprehensive and unflinching account of the country’s experience during the two waves of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Through a combination of ground reports, data, and personal knowledge, Mander sheds light on the grim reality of the situation that went beyond mere underreporting of cases and deaths.

The first part of the book delves into the humanitarian crisis of 2020, brought about by public policy choices, leading to the devastation of livelihoods, particularly affecting the urban poor and migrant workers. The second part records the horrors of the subsequent year, marked by critical shortages of medical resources and the neglect of public health.

Defence Colony is one of Delhi’s affluent neighbourhoods, tree-lined, centrally located, with wide roads, parks and many popular restaurants. Early into the first lockdown, tragedy hit one of its sprawling apartments. A couple in their 80s, and their son, all tested positive for Covid-19. The older man tragically died in hospital, his wife was discharged, and his son fought for his life for a long time on a ventilator. Fortunately, he survived.

Through all of this, a person from the family thought it fit to call the local police to complain about their security guard. They wanted to blame someone for the tragedy that had engulfed their family. Their security guard was Muslim. That was reason enough for them to surmise that he had secretly participated in the Tablighi Jamaat congregation in Nizamuddin. They were convinced that it was he who had brought the deadly infection into their home. The vigilant Delhi Police acted promptly on their complaint, registering crimes under Sections 188, 269 and 270 of the Indian Penal Code against the guard, charging him with a ‘negligent malignant act likely to spread infection of disease dangerous to life’. They also issued an advisory to the residents of Defence Colony to be careful of their domestic helpers who might bring the infection into their homes.

The matter was widely reported in the press, and there was popular outrage among readers and television viewers about the criminal irresponsibility of the security guard. He was reported by the police initially to be missing. They, however, quickly caught the fugitive, and sent him to be tested for Covid-19. He tested negative.

It was later revealed—with far less publicity—that the grandson of the Defence Colony household studied abroad, and had returned just before the lockdown by an international flight. It became evident that it was not the guard who had irresponsibly endangered the family. It was the family that had endangered the guard, by asking him to run errands for them in violation of the strict lockdown of the early weeks.

The police never satisfactorily explained why they filed a criminal case against the hapless guard. No one thought it fit to apologize to him. No one thought it fit to charge the family for violating curfew rules. A middle-class family in India finds it difficult to manage their lives without domestic help. Perhaps that was one reason why no one thought it fit to charge members of this household with imperilling the life of the security guard.

The story did not end there. Some weeks later, the same family employed an 18-year-old domestic helper. They arranged to get her tested for Covid-19. Three days later, the report came in. She had tested positive. It was 10 at night when the family read the report. They immediately turned her out onto the streets at that hour. She was distraught, and began to wail in the dark and empty lanes, not knowing where she should go, and how, this late at night in the midst of a curfew in a strange city. Some other residents came out of their homes to enquire when they heard her crying. The security guards also gathered around her. Among the residents was a doctor, who gave her a PPE kit. Someone called for an ambulance, others called up her male relative. One ambulance arrived, but refused to carry her as she was Covid-positive. Three hours later, a second ambulance finally took the frightened girl to hospital.

Writer Arundhati Roy, in a conversation with Karwan-e-Mohabbat, remarked that the coronavirus was not merely a deadly pathogen, but also an X-ray. It was an X-ray which exposed what we have done to our societies, to our planet: ‘this desolation that we call civilization, this greed that we call happiness, this horrifying injustice that we call “business as usual”…’

The traumatic months of the pandemic have indeed laid bare our badly broken society, and the near-complete estrangement of people of privilege from the working poor in India. They have revealed a people stunningly, shamefully at ease with inequality and privilege. They have confirmed that the veneer of modernity and the progressive, egalitarian values of the Constitution remain, in the prophetic words of Babasaheb Ambedkar, who led the drafting of the document, no deeper than a coat of paint.

[…]

‘If the spread of a global pandemic was an act of misfortune,’ writes legal philosopher Upendra Baxi, ‘its catastrophization has to be located in the injustices of social structure and policy. On the other side, the spectacular emergence of new communities of belonging (social groups trying to meet the many needs of migrants on the move), which counter the politics of creating communities of danger, hopefully will become a post-Covid-19 future, ending forever the production of social indifference.’

Arundhati Roy too writes luminously of the pandemic as ‘a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it’.

Among the carcasses that we must leave behind are those of our disgraceful moral collapse, of economic and social arrangements that privilege some lives while treating millions of the rest as expendable.

Can we indeed resolve to fight to build back better? Can we use the moment of this crisis, the gravest that we have faced in many decades, as a portal to rebuild our broken country into one which is more compassionate, more just and more equal? Can we transform this time of loss, grief and rage into a moment of civilizational introspection, a recognition of the collapse of our moral centre as a nation and as a people? Can we negotiate a whole new social contract—of people with their governments, and people with each other. A social contract which recognizes our shared sisterhood and brotherhood, and which recognizes that our destinies are welded together. That we all, every one of us, belong to and with each other.

There is no better time to recall the talisman Mahatma Gandhi left for us. When in doubt and confusion—he counselled in a letter he wrote just months before he was killed—think of the most vulnerable person you know, and ask if the measures you intend to take will improve her life and freedom. The measures the state opted for during the pandemic may arguably have protected you and me, but they wrought havoc on this last person Gandhiji had asked us to remember before we took any step. If policy-makers had held to their hearts the talisman which the father of our nation left for us, they could never have opted for a lockdown which destroyed, in one fell blow, her livelihood, her savings, her already tenuous support structures, her dignity, her trust and her hope. Light years away from the vision of Mahatma Gandhi, the arrogance and casual cruelty of imposing a sudden, devastating and total lockdown was a transgression against the people of India. It was, and must be recognized to be, a crime against humanity.

Since the early days of the pandemic, a metaphor we heard very often was of war. Health professionals, governments and people the world over were fighting a war, indeed a world war, against a virus which threatened to destroy tens of thousands of lives, and, as some believed, even the world as we knew it. Every war has weapons. Some weapons were obvious in waging this ‘war’—science; medical infrastructure; public investment; state capacities; and the quality of political leadership. But the one element that is decisive in any such effort was left out of most conversations. This was solidarity. Indeed, the pandemic was not a war, because in a war some people win and some people are defeated. But with Covid-19, no one set of people could be victors if any other people were defeated. It was instead a struggle for collective human survival. There were no exits for individual escape; solidarity—between classes and between nations—alone could enable us to overcome. We should have recognized that we could only overcome together.

Having suffered the largely self-inflicted wounds of the Covid-19 crisis, are we ready to face the future not just with courage, equanimity and faith in science, but also an incandescent solidarity that rises gloriously above the tall walls of national boundaries, class, wealth, gender, race and caste? Together, will we at last build a world that is kinder, more equal and more just, and therefore far better equipped to prevent and confront such a global health and humanitarian crisis the next time it hits?