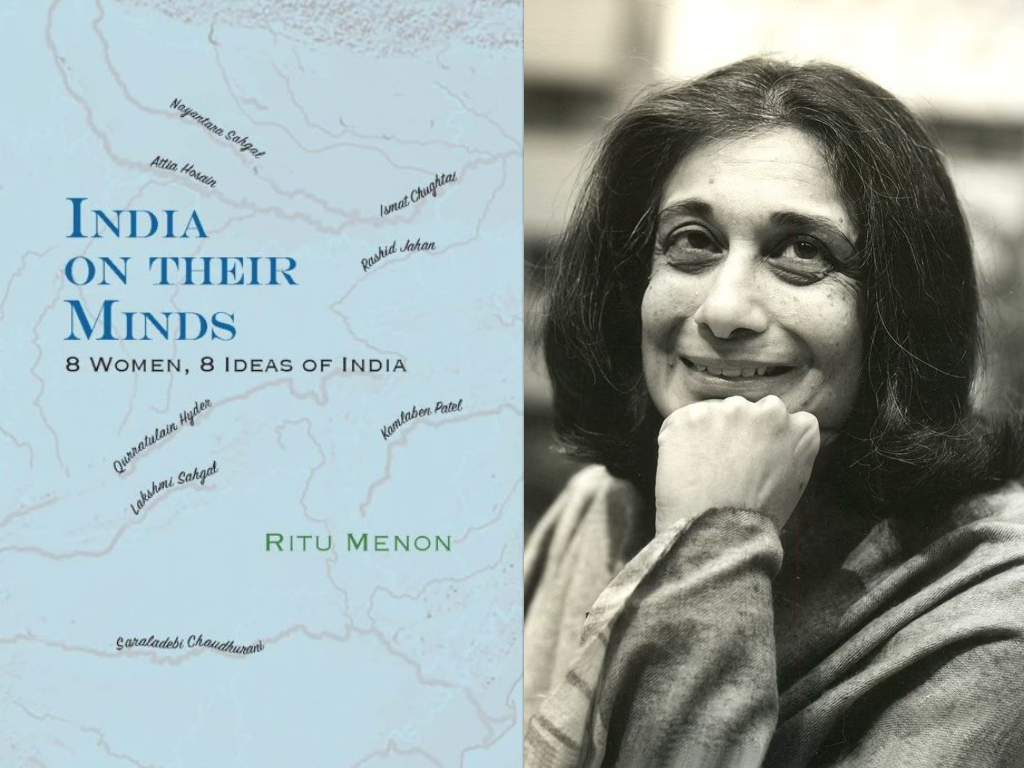

Edited by Ritu Menon, India On Their Minds: 8 Women, 8 Ideas Of India (Women Unlimited, 2023) is a collection of writings by eight women who witnessed and participated in the events leading up to India’s independence from colonial rule. These women, through their short stories, novels, essays, memoirs, and autobiographies, documented the birth of the nation and its aftermath, reflecting on the impact of these events on individual lives.

In this conversation, author and publisher Ritu Menon speaks of the many-layered personal and political voices of eight different women: Nayantara Sahgal, Captain Lakshmi Sahgal, Rashid Jahan, Ismat Chugtai, Qurratulain Hyder, Attia Hosain, Kamlaben Patel, and Saraladebi Chaudhurani. What brings these women together? All of them raised their voices as “interlocutors, participants, and commentators, in the life of the country(ies) they lived in.” And all were deeply committed to the idea of an inclusive, diverse, egalitarian and secular nation.

Githa Hariharan (GH): You have described these eight women’s ideas of India as a combination of ‘the personal, the professional and the political’. Would you elaborate on this, keeping in mind the diversity of the women that you have included in the book?

Ritu Menon (RM): It’s more of a deduction, rather than a description, actually, as only two of the women, Lakshmi Sehgal and Rashid Jahan, were ‘professional’ in the generally accepted definition of the term — they were practising doctors. But social work, which is what Kamlaben Patel and Saraladebi Chaudhurani engaged in for a good part of their lives, is considered a profession today; and script-writing, broadcasting, and editing, which is what Ismat Chughtai, Qurratulain Hyder and Attia Hosain did on a regular basis, are certainly considered to be that, although none of them was ‘qualified’ for the job. Nayantara Sahgal, by virtue of her journalistic writing, would be called a columnist today, in addition to being a novelist.

In that sense, yes, they could be thought of as professional women, but the important point is that, however they defined themselves, their writing — even Kamlaben Patel’s — was nothing if not political in intent. And it was through their writing that they made a strong political point, and intervened in the life of the country by commenting on it, and on what was going on. That politics sprang from deeply felt, personal choices that each woman made, that had a direct bearing on how she thought of herself as a political being.

That said, Lakshmi Sehgal and Rashid Jahan were directly involved, politically, as well — Sehgal as part of the Rani Jhansi Regiment in the Indian National Army, and later in the CPI(M) and AIDWA [All India Democratic Women’s Association]; Jahan as an active member of the Communist Party of India, from its inception. Ismat Chughtai was part of the Progressive Writers’ Movement; Saraladebi Chaudhurani was politically active through her public engagements in Calcutta and Lahore, and via the journal she edited, Bharati. Nayantara Sahgal was steeped in politics, given her family background, and it provided her with the context, as well as the material, for all her writing. Hyder and Hosain’s novels, short stories and non-fiction drew their inspiration from an acute understanding of ‘politics’, notwithstanding the fact that they may have chosen to remain independent of formal political affiliation. Their personal life choices were nothing if not deeply political.

GH: In what ways would you say independence from colonial rule, Partition, and the birth of the ‘nation’ were defining moments for the lives of these women — and also for their ideas of India?

RM: All three interlinked events were watershed moments for all eight women, and all of them were unalterably affected by them. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for the fervour and energy of the freedom movement and for the fact of independence, followed by Partition, I would venture to say that they may well have written differently. Except for Rashid Jahan (who died soon after Independence and we can’t know how she would have responded), all of them grappled with what this simultaneous freedom and division meant, for them personally, as well as for India. The only writer not to have dealt with Partition in her writing, is Nayantara Sahgal; for her INDIA was her main character, rather than any single moment or event. And Saraladebi had retreated into a life of spirituality before Independence.

Hyder, Chughtai, and Hosain remained preoccupied with the idea of what this new, independent India meant to them, and of how they should relate to ‘nation’ and ‘country’, and certainly all of Hyder’s major work dealt with this conundrum, in one way or another. Lakshmi Sahgal and Kamlaben Patel, post-Independence, withdrew from an active political life, in Patel’s case, permanently. Yet they wrote. And it is through their writing that we get an insight into how they responded to these epochal events. It is also through their writing that we understand the ‘political’ differently, because they wrote it as women. Inevitably, it would offer another perspective on, and experience of, a politically aware life. This fact leaps out of all their writing, fiction or non-fiction.

Also read: Excerpts from India on Their Minds

GH: All eight women address, in some way or the other, the concept of nationalism current in their times. Their understanding of nationalism naturally informs their practice of the concept in their writing, their activism, and their choice of alliances or allegiance. How do you think they have responded, or would respond, to the different brand of ‘nationalism’ that is on the ascendant today?

RM: I realised, almost serendipitously, as I was writing, that of the eight women, four were Hindu, four Muslim. These may have been subliminal identities before Independence, but Partition reconstituted them radically, and each writer was confronted with the question of where, and how, she ‘belonged’ in this redrawn, redefined ‘country’. No longer could they think of the ‘nation’ in uninflected, ungendered terms. Kamlaben Patel expresses this existential anxiety with anguish, as she was compelled to deal with it at an urgent, human level. Hyder and Hosain are possibly the most eloquent, they also had to ‘choose’ ‘their’ country, but it was a choice enjoined on, not ‘chosen’ by, them. Chughtai chose, too, and in the bargain, all of them lost.

We know how Hyder and Nayantara Sahgal would have responded to today’s brand of nationalism, because they have written about it. Unequivocally, and with mounting despair at the betrayal of an original, aspirational idea that liberation and freedom represented, notwithstanding the tearing asunder of the country at Partition.

Do women have a country? How is it, and one’s place in it, to be understood? Hyder, for one, addresses this question, sometimes frontally, at other times elliptically, and all her protagonists contend with it throughout their lives. One cannot speculate, but if I were to go by what they wrote and said, by how they lived their lives, I would say that every one of these eight women would have rejected the nationalism on display today. They would have chosen whom, and what, to align with today, as they chose then, to uphold those ideas of India that are inclusive, diverse, egalitarian and secular.

Again serendipitously, the eight women in the book personify the kind of diversity that allowed me, writing about them, to foreground the very personal, very political, very gendered, voices they raised as interlocutors, participants, and commentators, in the life of the country(ies) they lived in.