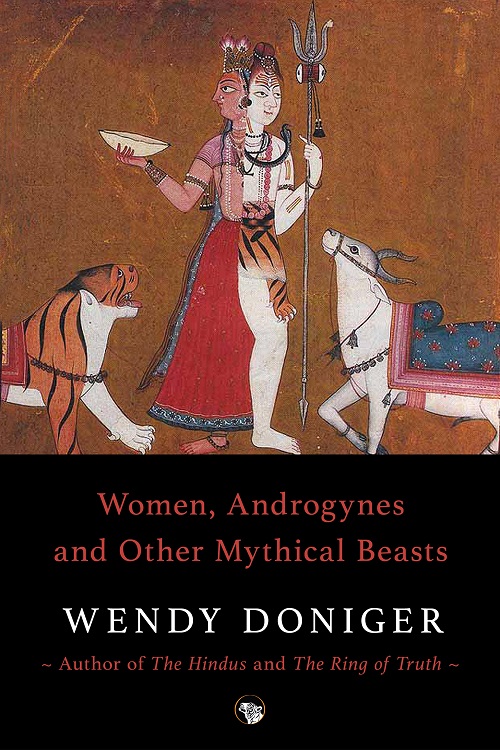

Wendy Doniger’s Women, Androgynes and Other Mythical Beasts (Speaking Tiger, 2023) explores gender and sexual identities in Hindu, Buddhist, and Tantric mythologies. It takes us from the union of ‘mother earth’ and ‘father sky’ in the Rig Veda to Shiva’s burning of Kama, the god of desire. The author explores the complex portrayal of dominant women and goddesses in Hindu mythology.

The book delves into the dichotomy between the non-maternal and maternal goddess, the inequality of power structures, and the emergence of a new Goddess in medieval India. The worshiper’s relationship with the Goddess, her ambivalence, and the longing for her presence shed light on the multifaceted nature of devotion in Hinduism.

The following are two excerpts from the book.

The dominant woman is dangerous in Hindu mythology, and the dominant goddess expresses this danger in several different but closely related ways. She appears as the killer of her demon suitor, beheading him in a symbolic castration; she dances on the corpse of her consort… This is the non-maternal goddess, with whom the worshiper does not dare seek erotic contact for fear of losing his powers. But the dominant woman also appears as the mother goddess, with whom the worshiper does not dare seek erotic contact for fear of incest. On the human level, the dangerous woman is the wife whose sexuality is regarded as a threat to her husband, either as the erotic woman, who will drain him of his life, or as the maternal woman, who conjures up the specter of maternal incest. Indeed, these two roles merge in the figure of the sexually aggressive mother, a recurrent image in myths and a persistent stereotype in conventional perceptions of Hindu family relationships. The dichotomy between male authority and female power on the human level provides new conflicts when it sets a pattern on which divine hierogamies are modeled: any woman, especially a goddess, has power, but this power is tamed by making her subservient to her husband; the dominant goddess, however, adds to her power an authority (by virtue of her divinity as well as by her independent character) that violates the basic Hindu categories of male-female relationships.

Throughout this corpus of myths there is an inequality of power structures between male and female deities. In bhakti mythology the worshiper is encouraged to seek an erotic liaison with a male god even if this means that the worshiper must change from male to female, but he is not encouraged to seek such a relationship with a goddess. In classical mythology, the god usually succeeds in committing incest with his daughter; this is in part because the male is not split as the female is (i.e., he may become a father without ceasing to be a consort) and in part because the system encourages sexual contact between an older, dominant man and a younger, weaker woman but not between an older, dominant female and a younger, weaker man. The mother goddess, by contrast, does not usually succeed in committing incest with her son; the son, however, may initiate an erotic liaison with the mother. This inequality also extends to the problem of love in separation, in which the woman’s longing is greater than the man’s, just as the worshiper’s longing for the god is greater than the god’s longing for the worshiper. For in orthodox mythology as well as in bhakti, the woman represents the devotee, mediating between the male worshiper and the male god or the goddess.

[…]

Also Read: Excerpts from After the War by Wendy Doniger.

By the time of the flowering of Saktism in medieval India, between the tenth and fifteenth centuries A.D., a new Goddess had emerged, one who remains a potent figure in contemporary Hinduism. Among the factors that combined to produce her were the resurgence of non-Aryan (perhaps even pre-Aryan) local cults of the Goddess, the increasing importance of widespread regional cults of ambivalent figures like Sitala and Manasa, and the pervasive contributions of Tantrism to nonTantric Hinduism.

This new Goddess was perhaps not so new at all. The Tantric ritual view had roots in the ancient Vedic ceremony of the chaste student and the prostitute (Mircea Eliade; Yoga: Immortality and Freedom), which had been rejected by the orthodox Vedic tradition but filtered back into non-Tantric Hinduism, where it confronted the image of the dangerous mare and the safe cow. The result was that, in the local and regional cults of the Goddess in India, the ancient ambivalence characteristic of the full Goddess was revalidated, fully integrated—a step that went far beyond the mere onedimensional inversion of an equally one-dimensional orthodox Hindu model. This full goddess remains the object of worship for many Hindus today.

When the Goddess is worshiped and accepted in her full ambivalence, the worshiper asks her to be present with him always. But if part of her nature is pestilence and mindless destruction, why should one want her near? Why not merely placate her and ask her to go away? The answer to this may lie, in part, in her maternal nature: “The central feature of the ‘good mother,’ incorporated by every major goddess in the Hindu pantheon and dramatized either in her origins or in her function, is not her capacity to feed but to provide life-giving reassurance through her pervasive presence” (Sudhir Kakar; The Inner World). If the essential function of the Goddess is to be there for you, you want her there even when she is in her shadow aspect. The only unbearable harm that the Goddess can inflict on the worshiper is to abandon him, as the immortal mare so often does, fleeing from her mortal consort, abandoning her child. This, not the mutilation, is the source of devastating grief, the terrible longing for the vanished divinity, the cruel pangs of viraha. The only evil mother is the one who is not there.

Also Read: “Truth and reconciliation require the shedding of aggressive masculinity”

Here, perhaps, is the key to the distinction between demonic goddesses and straight demonesses: you worship demons to get them to go away, but you worship gods, even demonic gods, to get them to come to you. One way out of the dilemma of eating the mare or being eaten by her was to refuse to eat the female animal (the cow) so that she would not eat you: “If you kill the cow, who is your mother, then in some future lifetime your mother will kill you.” (Srila Prabhupada; Back to Godhead) But the one who does not retreat from incestuous cannibalism attains freedom from all normal human constraints.

Thus the worshiper invokes Sitala even though she will infect him with smallpox if she comes to him; without her, pestilent though she may be, life has no value. To allow the goddess to devour one takes courage; the goddess remains ambivalent, and being devoured is a risky form of worship. Even when she is gracious, to receive her grace is a terrifying and painful form of religious passion. But one has little choice: if that is the way that god is, what can one do? If she is denied, she is certain to be destructive; if she is worshiped, she may or not be destructive, and the worshiper may become immortal. The myth of Putana shows how the worshiper who treats god as a mother treats a son is assured of salvation—even if the worshiper takes the form of an aggressive, destructive mother. But this theology of bhakti implies a twoway flow: the deity, too, may become manifest in a destructive way and yet bring blessings, ultimate salvation, and rebirth.