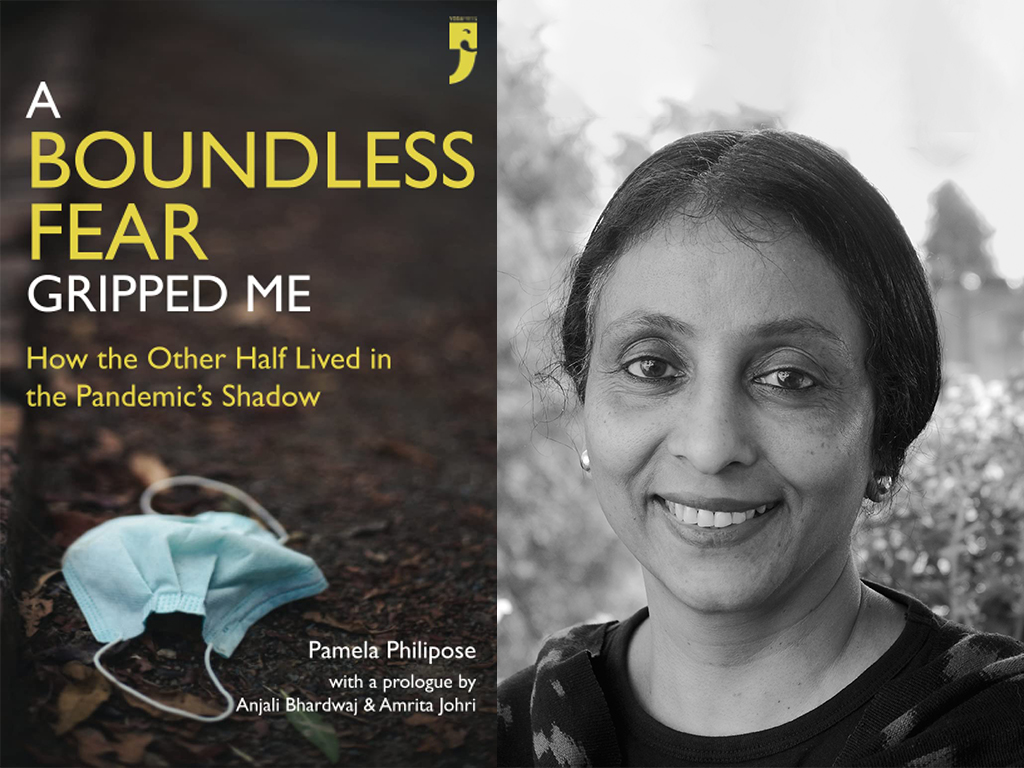

The lockdowns imposed by the government during the Covid-19 pandemic waves in India disproportionately affected the vulnerable sections of society. Pamela Philipose’s recent book A Boundless Fear Gripped Me, tells the story of ‘the other half’ who battled unemployment, debt, hunger, ill health, homelessness and impoverishment.

In a conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum about her book, Pamela Philipose talks about her motivation behind writing the book; the role of the media; public memory and the pandemic and more.

Indian Cultural Forum (ICF) : With the horrors of the pandemic still fresh, the book is not an easy read. It reminds us of our collective failure in safeguarding ‘the other half’. What motivated you to write this book and what conversations do you hope to get going through it?

Pamela Philipose (PP) : Looking back, how can the COVID-19 pandemic be described? We know that it was a once-in-a-century global health catastrophe as devastating as the Spanish Flu of 1918, with huge international social and economic impacts. But when it began, none of us even realised how life-changing it was to be, how it would touch every aspect of our existence — the way we lived and the way we died; the way we socialised and the way we managed our isolation; the way we ate, communicated with each other, and worked from home.

But what “we”, the more privileged often did not realize is that while the times were distressing for us; they were catastrophic for those living on the margins. The term “other half”, which figures in the title of this book was popularised by the economist and philosopher Susan George in her 1976 book, How the Other Half Dies The Real Reasons for World Hunger. She found that those most affected by hunger were often referred to in the passive voice, in the third person. In many ways, the pandemic discourse also suffered from a similar failing. We may have had some inkling of the suffering that the poorest in the country had to go through, especially after the lockdown in the first wave which triggered large-scale, unplanned migration of the labouring poor from our cities, but we never put faces and voices to that suffering. There were honourable exceptions, of course, but generally speaking everybody was so caught up in their own lives, that there was a failure to look beyond the personal.

One of my own wake-up calls was listening to the public hearings of women living in Delhi’s bastis which was organised by the Satark Nagrik Sangathan, a Delhi-based citizens’ group anchored by Anjali Bhardwaj and Amrita Johri, the works on rights and transparency issues. They conducted these hearings during the two waves of the pandemic, shining a light on the failure of the governments at the Centre and State, to perceive adequately how those in the lower tiers of society were being steadily ground down into the dust by the pandemic. That this was happening in Delhi, where the rulers of the country lived and where they did their policy-making, lent an additional layer of irony to the situation. Here were literally hundreds of thousands of people going to sleep on empty stomachs with their children, now out of school, literally driven to tears because they were hungry.

So when you ask, what motivated this book, I would say hearing these voices convinced me that these experiences need to be captured, told and retold, as living documents for the future.

ICF : What are the aspects of the pandemic that you think the media, especially the mainstream media and its reporting of the pandemic, failed to grasp?

PP : Location matters a great deal when media professionals do their reportage. Reports of how professional urban women working from home kept themselves in shape during the pandemic – a common enough trope in the publications of that time — would find many eager readers. Even a concept like “working from home”, was used blindly, without the realisation that this is a luxury that those who earn only by being physically present at their work sites do not have. We should not be surprised at this because over the years focus in many media houses has been the consumer rather than the citizen; the middle classes rather than the working class.

I would say that there was some empathetic coverage of the migrant worker initially, but once these bodies moved away from the frame, it was easy for the media to forget them. The central government in any case was keen that the media kept away from reporting on the migrant workers’ crisis, with the solicitor general even informing the Supreme Court that there were no migrants on the streets. So what became of these people who left the cities? How were they received back home? Did they face even greater challenges in the towns and villages from where they came? Those stories today are lost to us forever.

There was some important coverage on domestic violence – the trauma of women locked up with abusive, unemployed partners, did emerge here and there. To an extent the huge crisis of schooling did come out in the public, helped greatly by the amazing working of economists like Jean Dreze who documented how the loss of schooling was deepening inequalities in the country.

But the media failed in capture the everyday losses and traumas of this period; the anxiety of mothers not knowing how to respond when their children demand “something nice to eat”. The fear of older people that they have been forgotten by their families because of the stress of the times, for example, or the existential threat of being evicted from a tenement because of rent being overdue by several months. I could go on and on, but this book tries to capture some of these experiences in granular detail. I met, for example, an old man in a homeless shelter, who was living with the fear that his glasses would be stolen leaving him almost wholly blind. Stories like this fell by the wayside.

Read an extract from A Boundless Fear Gripped Me here.

ICF : Public memory can be fickle — what are the risks of the pandemic being erased from it? Will it, like the previous pandemics, so vividly captured in literature, be forgotten and what are the dangers of it?

PP : You are absolutely right — public memory is extremely fickle. Perhaps because we are living in highly mediatised times, it may not be likely that we would completely forget the risks. After all, just think back to the days of the Bengal famine. Although there was no internet, digital cameras, and the like, we still had some brilliant documentation, whether through the images of a Sunil Janah, or the powerful illustrations of a Chittaprosad.

Yet, what is of concern is that with all the material on this pandemic that is now available to us through journalism, academic scholarship and civil society documentation, important truths continue to be elusive. It becomes crucial therefore to make the realities of those days visible because they reveal the “negative sequential effects” of a broad spectrum of phenomena like unemployment which can, in turn, lead to disruptions and deprivations ranging from nutritional insecurity to psychological breakdown. The pressure on many to sell “movables” like pieces of jewellery to feed their families, depriving them of their only means of security in times of acute financial distress, is a case in point. The COVID-19 pandemic thrust this section of society into a downward spiral that saw their savings, which they had painfully built up over the years, get emptied out in a matter of weeks. Insights like these should never be forgotten.

ICF : It has been three years since the pandemic hit. Do you think the government has learned anything from failing to safeguard people and contain the disease? Have any policies/directives been informed from this experience, especially so history never repeats itself?

PP : One very conspicuous development during those two waves of the pandemic was how corporate India benefitted from the crisis. A major marker of the pandemic was the unprecedented growth in the wealth of the richest segment of the population. Indian billionaires increased their net worth by 35 per cent between the months of April and July, 2020 indicating that the state’s policy-making favoured the corporate sector in a climate of great opacity. So the Indian state may have done a few things right, even if somewhat delayed, such as initiating special ‘Shramik’ trains for migrants, but it was also the case that it allowed profiteers to flourish. In late March 2020, the PM CARES funds were used to procure 10,000 ventilators from the Gujarat-based AgVa Healthcare, which claimed to have developed low-cost, “made in India”, ventilators in just 10 days. It soon became apparent that a large number of these machines were not in working order and by June that year, expert committees were flagging doubts about their reliability. This was just one instance of the cavalier and commercially-driven way in which the procurement of life-saving equipment was conducted amidst a welter of false claims. I don’t believe there has been sufficient attention paid by the media to the innumerable ways in which the government let down the people of India during the pandemic.

Given this reality, it is very likely that history will indeed repeat itself when the country is faced with another pan-national crisis of this kind. That is the sad truth and we, as part of civil society, must be alert to the huge gaps that came into view this time – all the more so because of the self-congratulatory mode that the government has adopted on its handling of the pandemic.