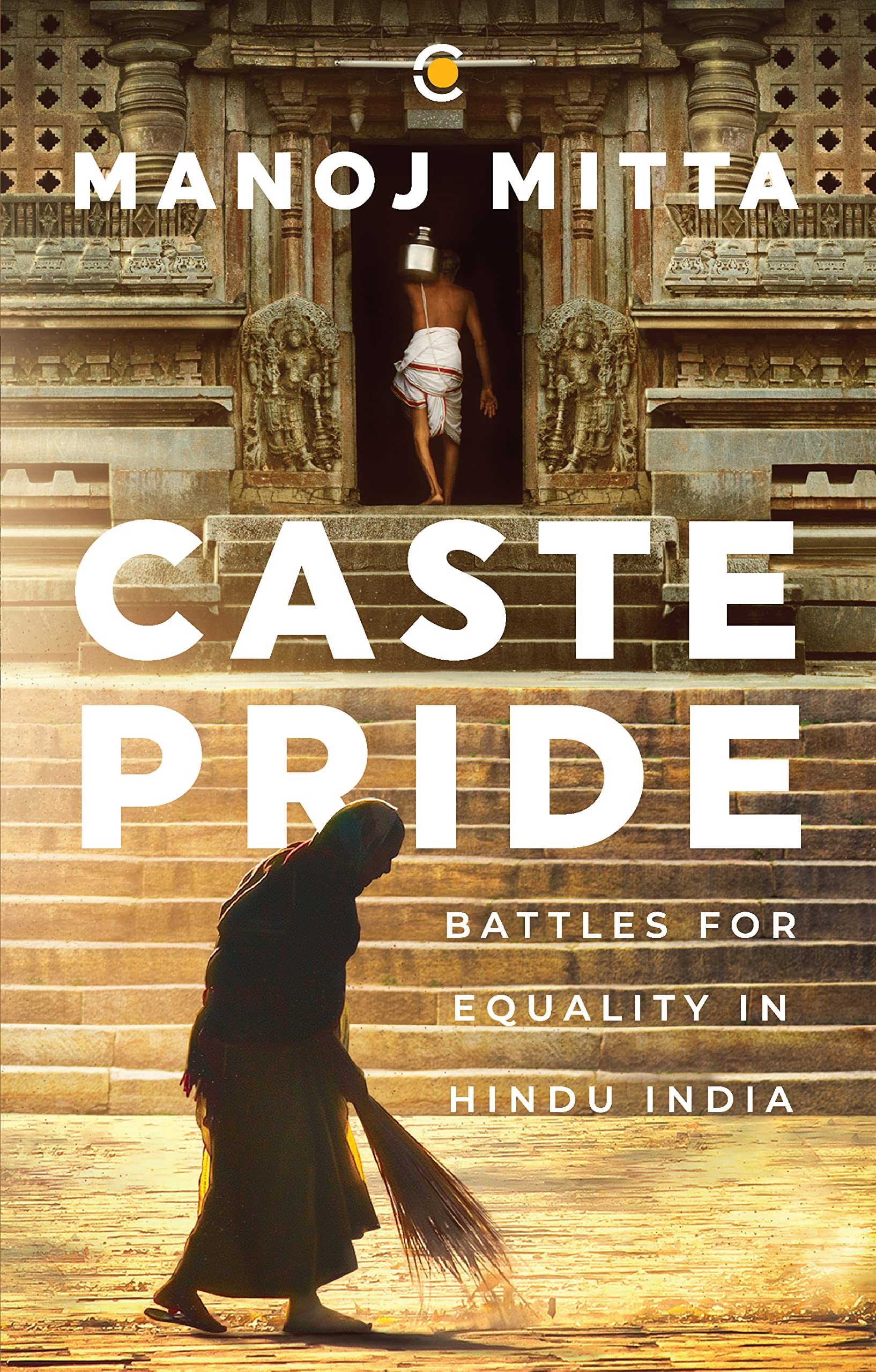

Manoj Mitta’s book Caste Pride (Westland Books, 2023) examines the enduring violence of the Hindu caste system through a legal lens. It uncovers the characters, speeches, and decisions that have shaped the battle against caste discrimination. The book celebrates pioneers from various castes and highlights the contributions of non-Hindu leaders. Mitta reexamines the positions of prominent figures and reveals how caste prejudice persists. The book establishes that untouchability is just one aspect of a broader hierarchy that affects everyone’s freedom.

Of all the laws enacted during his eight-year tenure as governor general, Act XXI of 1850, according to one of his biographies, ‘was always regarded by Lord Dalhousie as the most important of those passed by him’. To be sure, he is remembered more for introducing railways, telegraph and uniform postal service in India, and for pursuing the doctrine of lapse and expanding the domain of British India in the lead-up to the 1857 uprising. Dalhousie gets little credit in popular history for being instrumental in striking a blow against caste—however nominally—for the first time ever in a national legislation. More than a century after its enactment, an American scholar of social justice in India, Marc Galanter, wrotethat the 1850 law was the ‘only legislation during the British period bearing directly on caste autonomy’.

So much so that, in 1897, when the legislature conferred ‘short titles’ on several old laws, Act XXI of 1850 came to be formally named as the Caste Disabilities Removal Act, 1850. The rationale behind the Short Titles Act, 1897 was to follow in India what had by then become a practice in England, that ‘every Act should be capable of being cited by means of a short title’. Given that the original intent behind the enactment of the 1850 law was only to protect the inheritance rights of apostates, Lord Elgin, who was the viceroy of India in 1897, could well have named it the Freedom of Religion Act or the Religious Disabilities Removal Act. After all, there was just a passing reference to caste in that single-clause law.

That Elgin’s Legislative Council chose to highlight the caste angle in the short title was perhaps a sign of the growing colonial understanding of the dynamics peculiar to Hindu society. Or the choice might have been made with a political intent, to put the emerging band of Hindu nationalists on the defensive by drawing attention to the caste divisions inherent to their community.

The title was misleading though. Far from the impression conveyed by its overbroad title, the 1850 law was limited to protecting the civil rights of those who had, for whatever reason, been ‘deprived of caste’. Everyday issues of caste prejudice—such as restrictions on members of lower castes from accessing public spaces and on members of any caste from dining with, let alone marrying, members of other castes on pain of excommunication— fell outside the scope of this law.

But then, before the law even had a name, conservative Hindus already saw it as loaded against them. Consider this file noting by a Fort William official in 1893: ‘It is easy to see why a Hindu should object to Act XXI of 1850. Practically there are no converts to Hinduism except from aboriginal tribes, who scarcely come before the courts, whilst converts are made from Hinduism.’

That the 1850 law facilitated a one-way street out of their fold rankled Hindu nationalists for decades. In 1927, a legislative proposal was made by N.C. Kelkar, who was the late Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s political follower, journalistic successor and biographer. He was also a leader of the Hindu Mahasabha and a member of the Central Legislative Assembly, the forerunner of the Lok Sabha. In December 1927, Kelkar introduced a bill that sought to repeal the Caste Disabilities Removal Act, 1850.

Watch: A Conversation with Manoj Mitta on Caste Pride

It was not the first time that a native legislator had moved to get rid of a national law enacted by the colonial masters. The 1816 Madras regulation prescribing confinement in the stocks for lowercaste offenders had been repealed in 1919 due to similar attempts by Indian legislators.

The difference, however, was that Kelkar’s 1927 bill sought to undo what was a social reform, at least in the eyes of progressive Hindus. To discredit the 1850 law, he stressed on the absence of any Indian lawmaker’s involvement in its enactment. As his formal SOR put it, ‘The Caste Disabilities Removal Act was purely a Government measure and does not represent the will of the people.’

In the event, Kelkar’s bill served as an opportunity for rival Hindu voices to be heard for the first time in the national legislature. It led to a counterblast from fellow legislator Hari Singh Gour who saw the 1850 law as a social reform that needed to remain in the statute book. In social terms, it was a debate between a conservative Brahmin from Poona and a progressive Kshatriya from Sagar, in what was then called the Central Provinces.

Like East and Bethune, Gour too was associated with the founding of educational institutions. A jurist who had a doctorate in law from Cambridge and post-doctorate from Dublin, he was the first vice chancellor of Delhi University when it was established in 1922. It was an exceptional honour for an Indian to be the first head of a university that the British had opened in their new capital. Subsequent to his term in Delhi, Gour served twice as vice chancellor of Nagpur University. His crowning glory though was a university he set up in Sagar, his home town, in 1946, with the money he had made as a leading lawyer. Until his death three years later, Gour served as the first vice chancellor of Sagar University, the oldest institute of higher learning in what is today Madhya Pradesh. It has since been renamed Dr Hari Singh Gour University. His seminal books on law included The Hindu Code, which was published in 1919.

In his parallel avatar as a national legislator from 1921 to 1934, Gour served as the moving force behind a range of social reforms, including one that he believed complemented the 1850 law. The scriptural basis on which Hindus had traditionally denied inheritance rights to an excommunicated family member was an injunction from Manu, that most controversial of law-givers of antiquity. Chapter IX, Verse 201 of the Manusmriti denied inheritance rights even to Hindus suffering from other disabilities. As the authoritative translation of the time put it, ‘Eunuchs and outcastes, persons born blind or deaf, madmen, idiots, the dumb, and such as have lost the use of a limb, are excluded from a share of the heritage.’

It was in defiance of this injunction that Gour introduced a bill in October 1927, stipulating that other than a born lunatic, no Hindu shall be excluded from inheritance ‘by reason only of any disease, deformity, or physical or mental defect’. He also cited judgments that had, on the strength of the Shastric or classical Hindu law, discriminated against vulnerable people. The Central Legislative Assembly passed the Hindu Inheritance (Removal of Disabilities) Bill on 22 March 1928. Four days later, there was a heated exchange between Gour and Kelkar when the latter’s bill to repeal the 1850 law came up for discussion in the same House.