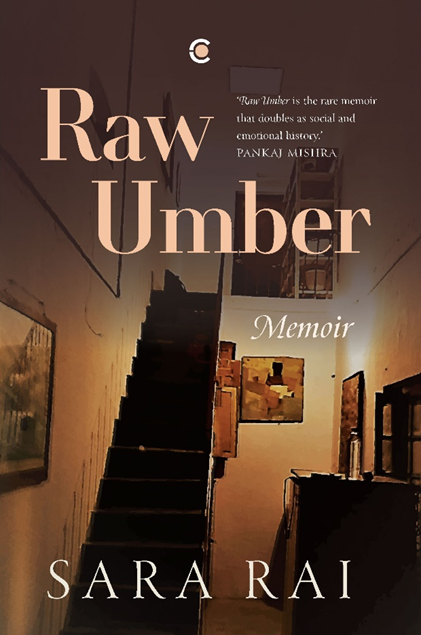

Sara Rai’s memoir Raw Umber is as much about the steady pulse of the author’s childhood in the 1960s as it is about the nature of remembering and the role that memory plays in shaping a writer’s sensibility. The book also talks about her early years spent in Allahabad and Banaras, her family, and what it has meant to be the granddaughter of a figure like Premchand.

The following are two excerpts from the book.

When I was in my late teens and still undecided which language to write in, he had told me that the language one is born into, one’s mother tongue, can be the only medium for creative expression.

My father’s statement about the mother tongue stayed with me when I started writing, late, my fiction in Hindi. Another thing that I barely acknowledged even to myself was that I felt something like shame whenever I thought of writing in English. It seemed wrong that a granddaughter of Premchand should be doing so. Our family had a certain linguistic pride. I knew that Premchand was famous, but I had not realised the extent of his popularity. In the Hindi class at St Mary’s Convent School where I studied in Allahabad, the teacher would point me out to the other children when we came to the Premchand story, and everyone would turn to look at me. This was the moment I’d been dreading from the beginning of term, and now the moment had arrived. This was only the beginning. The fact of Premchand, that I was his granddaughter followed me everywhere. Everyone had a story to tell about their personal engagement with his fiction—the shopkeeper woman who went to dusty bookracks overhung with cobwebs in a dark, neglected village library in Bihar to find his books with the help of a candle; the long time cook in my father’s Delhi house, Ramchander, who wept over Premchand’s story ‘Alagyojha’ (Divided Hearths) that he read between cooking meals; the cyclist whom we met at a wayside tea stall in Gopiganj, where we’d stopped while driving to Benares, who recited whole passages from a favourite story. The list was long, for everyone seemed to have read Premchand. Ironically, it was this very ubiquity, the reverence and love that he inspired in people, that made him something too large for me to comprehend in the early years of my life. It led also to a paradoxical feeling that, without having read it, just by being related to him I had somehow inhaled his writing! The reading happened much later.

The connection with Premchand was only one of the things that contributed to my confusion about which language to write in. And the question was never quite settled for me. I had been born into Hindustani, the mix of Hindi and Urdu that we spoke at home. We were forbidden to speak in Hindi at the Englishmedium school I went to, and transgressions were punished with a fine. We were embarrassed to speak in English at home. I did not know which my first language was. It felt more natural to be speaking in Hindustani. But the books I read were in English. Hindi textbooks, the ones we came across in school, despite the rare interesting story, had seen to it that we stayed off Hindi literature for a long time. It was only later, when my father needed some help in sifting through the hundreds of stories that were sent for publication in Kahani, that I found myself reading Hindi literature. I could write more freely in English, being accustomed to it from school. So much so that when my early stories started appearing in Hindi, someone asked me whether I had written them in Roman. As a four-year-old, I was on the lookout for simple ways to convert Hindi words into English, for I could not speak it yet—‘khilao-d’ ‘baithao-d’ ‘sulao-d’ (fed, seated, made to sleep)—as if merely adding a ‘d’ to the Hindi word made it English! The preoccupation with language went back a long way. The first story I ever wrote was in English. It was titled ‘Lucky Horace’. I was eight years old at the time, and the story was modelled on the Enid Blyton books that I had read when I was very young.

While still in my teens, I’d started translating into English stories from Hindi and, later, some from Urdu and some from English into Hindi. I now see that this was all a process of fumbling, of groping for a language that could be my own. I’d wake up one morning and start writing in English, or even wake from much later that a startling realisation came to me: it was possible to write in both Hindi and English. One language did not cancel out the other. This had not occurred to me as I flitted from one to the other language, my restlessness not finding the necessary repose in either. The situation was further complicated by the Urdu factor. The Hindi taught at school, heavily influenced by Sanskrit, was the punishing, burdened language that we never used in speech. What I wrote in, indeed could write in was Hindustani, the easy mix of Hindi and Urdu that we spoke at home. a dream in which I found myself writing in English, much after two of my short story collections had been published in Hindi. I was in a constant state of migration. It was only later, much later that a startling realisation came to me: it was possible to write in both Hindi and English. One language did not cancel out the other. This had not occurred to me as I flitted from one to the other language, my restlessness not finding the necessary repose in either. The situation was further complicated by the Urdu factor. The Hindi taught at school, heavily influenced by Sanskrit, was the punishing, burdened language that we never used in speech. What I wrote in, indeed could write in was Hindustani, the easy mix of Hindi and Urdu that we spoke at home.

[…]

Premchand’s own view on all of this was: ‘What is there in my life that I can talk about? It is a featureless, plain sort of life, the kind that millions of people lead in this country. A common householder caught in the problems of domesticity, a poor school teacher who kept pushing the pen all his life in the hope of some gain which did not come. What is extraordinary about any of this? I am like a grass reed swaying by the river and the wind makes sounds within me. That’s all there is to it. I have nothing of my own … my story is the story of the winds that sang within me.…’

He caught the ‘story of the winds’. Premchand himself was a voracious reader of the fantasies and romances current at the time. He talks about it in ‘Meri Pahli Rachna’ (My First Literary Work). Some of the much-read Urdu novelists of the time were Maulana Sharar, Pandit Ratan Nath Sarshar, Mirza Hadi Rusva and Maulvi Muhammad Ali of Hardoi. There was Maulana Faizi’s encyclopedic Tilism-e- Hoshruba and also Urdu translations of works by popular Victorian writers like George W. Reynolds who wrote city mysteries or ‘penny dreadfuls’. The most famous of these was a long narrative about the seedy underbelly of mid-nineteenth century London called The Mysteries of London. At the time, his father was posted in Gorakhpur. He was thirteen years old, studying in Class 8, and he describes how he would read these books at Buddhilal, the bookseller’s shop. Since he couldn’t sit there all day reading books, he started selling guide books and notes from the shop to the children at the mission school where he studied, in return for which he could take some of the books home. He read hundreds of novels in this way, and one can see how a creative universe was beginning to gather shape within him, a forming of opinions on literature and its role in society.

He soon became interested in writing. ‘I would write and tear it up, write and tear it up,’ he says about that time. The first piece he wrote at the age of thirteen was a play, and it was lost soon after it was written. It was about an affair between a distant uncle of his and a lower caste woman—he was settling scores with the uncle who frowned upon him for reading novels. He read the piece out to his friends to much hilarity. This ‘eye for an eye’ sort of writing was something that he would never return to. Rather he became serious about the role of the writer. It was the writer’s job to focus on the problems of society. But who would read such well intentioned, didactic writing? The work would first have to be entertaining in order to be read at all. How could it further any cause if it was dull and preachy? But at the same time, frivolity and sensationalism were to be avoided. In all his musings about literature with a purpose, what exactly was he fighting against? Corruption was rife then, as it is now, and there was a sharp caste and class divide with its consequent exploitation. There was no getting past indebtedness and money-lending. Then there was the malaise of untouchability, not to speak of the appalling condition of women, particularly widows—and all these problems were compounded by the presence of the British in the country.

So much to be written about—yet all that did get written were improbable tales of magic and romance. They went against the grain of his ideas about literature—in elaborating on these ideas, he does preach now and then. He had so much to say, and he was in a hurry to say it. All of his stories don’t quite make the mark, and need to be looked at as part of a changing, seeking imagination. He took the technique of writing a gripping tale from the Urdu dastans that he so enjoyed reading, and turned it to his own ends. The stories swing wildly from the didactic to depictions of psychology, from farce and irony to tragedy. He is never lacking in empathy for his characters; he looks at them from the inside. Each character’s point of view is presented so that even the darkest characters seem to be the way they are because they are driven by circumstance and not because they are intrinsically evil.