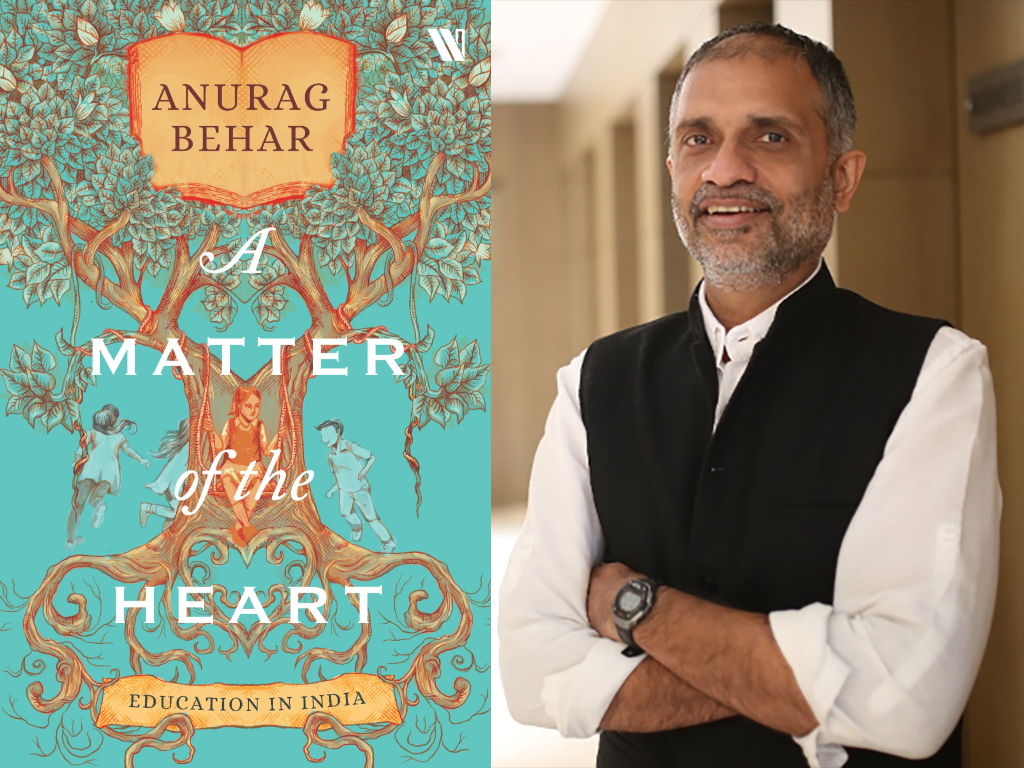

Anurag Behar’s A Matter of The Heart is a book about the state of education in India beyond the main cities and an ode to the educators who are shaping the future of our country.

Behar himself is a leading educationist and social sector leader in India and the CEO of the Azim Premji Foundation.

In this collection of essays, the author takes us to schools in remote villages in India. He gives us an insight into where our nation stands on education and, through that lens, into the nation itself. He shows us an India that is waiting for better infrastructure and one where the right to education is in constant struggle with the need for survival. But what emerges is the heart-warming and life-affirming story of how people and communities, energised from within, are changing lives — of individuals and the nation.

In this conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, he talks about his book, public education in India, the challenges that come with it, and more.

Githa Hariharan (GH): Despite the problems that beset public education in India, your book radiates a sense of optimism. So shall we start with the good news? In your rich range of ground reports, we discover that there are schools; village schools; government schools. There are teachers who struggle to make learning the adventure it should be. There are government education programmes and education officers to support the schools; and there are communities willing to be involved as well. Most of all, there are children, so many of them eager to learn, and occasionally astonishing you and me with an almost instinctive wisdom. Would you estimate the extent of the good news — the right track — with details from the ground?

Anurag Behar (AB): In the 12 years that the pieces in this book span, my optimism has only grown. That’s because I have discovered, and continue to discover, more good people and more good work than I thought I would.

Before I began to work in the social sector, and with education in particular, I spent many years in business. Without hesitation I can say that compared to people working in businesses, a larger proportion of teachers show exemplary dedication and inherent spirit. This is even more remarkable because they struggle for resources all the time. I think it’s not that better human beings become teachers. It is just that being a teacher is likely to make you a better human being. Because every day, you are faced with the responsibility of the future of scores of children, many of whom have little support from anywhere else.

GH: Now for the limits of good news, or the challenges, old and new. A longish list comes to mind, from the number of teachers and teacher training and curriculum, to the ‘local ownership’ of the school. Would you take us through the perennial challenges first?

AB: Indeed, there are many challenges, and most of them continue. There’s the poor quality of our teacher education system; the obsession with rote testing examinations; inadequate public expenditure and support to teachers; a culture of blaming teachers rather than empowering them, and inadequate alignment of all parts of the system with the stated objectives. These matters are in addition to the inherent challenges of education in a country like ours, with its diversity and economic disadvantages.

GH: Of the ‘new’ challenges before us, how do we view the usual, ongoing problems of public education in India, in the context of the losses that have occurred during the pandemic?

AB: Our schools were virtually shut for two years. Online education is ineffective. We knew that before, and it was tragically proven again during the pandemic. This has meant that our children have lost a huge amount of learning. States have to do a systematic job of helping teachers recover this lost learning. All states have some program to address this matter, but as you would expect, some are doing a good job of it and some are doing a very bad job of it. I am very apprehensive that too many of our children will grow up with this deep disadvantage, which will affect all later learning in their lives. Simply put: if a child in Class 6 today is not able to read and write, and we don’t ensure that she gains the capacity, but instead start teaching her the Class 6 syllabus, imagine what will happen to her later in education and life. I fear too many children are facing such a future, because many states are very slipshod in their approach to this emergency.

Also read | An extract from A Matter of the Heart.

GH: Again, the challenges specific to the times: in an atmosphere of division, of easily transmitted prejudice, or easily spread irrational theories, how do we foster the capacity to question? To develop a sense of critical enquiry — what our Constitution refers to as ‘scientific temper’?

AB: This can be enabled by the syllabus and textbooks. But this can be truly developed only by the behaviour of teachers, and the relationships they build in the school. It’s the culture (including the practices) of the school that encourages critical thinking, fosters inclusion and non-discriminatory behaviour, and fosters other similar capacities and dispositions. Our system and curriculum must focus significantly on the school culture, practices, and arrangements.

GH: If our collective goal is universal education of a particular quality — let’s say knowledge, and methods of gaining knowledge, rather than mere information gathering — how do we strengthen public education through policy? Through budgetary support? Through access to libraries, films, people who excel in their fields?

AB: Without question, we need greater investment. But that is insufficient. It is a matter of the capacity of our teachers and the quality of our teaching and learning material. We do not need anything fancy. Committed and high-capacity teachers with support from the system — which includes adequate resources — can make his happen.

GH: For education to be meaningful in India, it has to increase knowledge of, and sensitivity toward, our diversity. How do we do this in terms of language, for example? How do we introduce translation as an everyday practice? Where does English fit in the village schools you write about?

AB: Sensitivity towards diversity and other dispositions should be deeply embedded in the overall curriculum of schools. That includes the books, the pedagogical methods, the arrangements in schools and the school culture.

The social reality of India is that learning English is aspirational — that is true of villages as well. However, it is very clear that from an educational perspective, children learn literacy best in a familiar language, which is often their mother tongue. So literacy should happen through a familiar language and, in addition, children should learn many languages, including English.

GH: Like your daughter who listed the ‘girl-hating’ points in a textbook, I used to edit school texts as a young woman to ‘sneak in’ some awareness of gender equality. But of course, there is so much more to do — in the textbooks, yes, but also in actual practice in schools — toward those who are marked out in a range of negative ways because of their caste or gender or sexuality; because they are Muslim or Christian or Adivasi; or even because of the region they come from. Surely this is a fundamental task of the socialising experience for both children and adults in a school? And how do we grapple with this task in our times when people are so easily reduced to a single identity?

AB: Education and school can only play so much of a role. I feel that we too often put too much burden on schools for too many of the problems of our society. Schools make up only one kind of social institution. They must play their role, but they cannot compensate for other social institutions, processes, and dynamics. On the matter of how to do this in schools, it has to be deeply embedded in the entire curriculum, from the content and pedagogy, to school culture.

GH: The best thing about your book, in my view, is that it discusses education in terms of practice — real schools in real villages — and not in some abstract way with acronyms and bullet points. How do we involve civil society groups, university students — the community at different levels — in the education of our children as well as teachers?

AB: Civil society groups, university students and others can play useful roles in education. For example, they can mobilise the community, or help with resources, or advocacy with local government.

The one thing that I would caution against is well-intentioned people trying to teach when they are not teachers. Such people should go through adequate preparation before they become teachers. This is simply because teaching is by far the most complex of human professions. But too many people think that just because they have been educated, they can also teach. We must develop a societal understanding of the complexity of the teacher’s role and her huge contribution, which is what will give it the respect that it deserves.