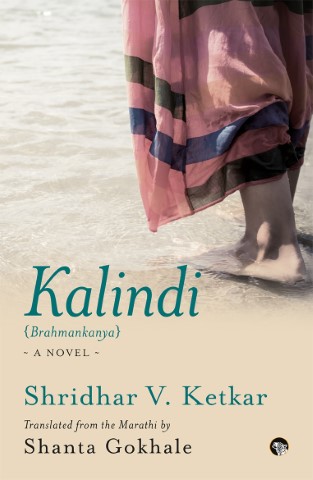

Shridhar V Ketkar’s Kalindi (Speaking Tiger, 2022), translated from Marathi by Shanta Gokhale, originally published as Brahmankanya in 1930, has been hailed as brave and ahead of its time. It brings the classic alive for the contemporary reader, and we see how relevant it remains almost a century later.

It is the early 1900s in Mumbai. Educated and financially independent, Kalindi Dagge dreams of living in a casteless and equitable society as a single mother—a life far removed from the one she had in the stifling world she left behind. A world where she was the daughter of a brahmin lawyer, Appasaheb Dagge, and the casteless Shanta; and the granddaughter of another brahmin and his schoolteacher mistress who rejected the idea of marriage. A world in which she was an outcast; the daughter of a man who rejected his caste but not his caste pride. A world where she had reclaimed her grandmother’s legacy and chosen, in defiance of family and society, to live as the mistress of Shivsharanappa, a Lingayat tobacco merchant, who later abandoned her and left her on the verge of suicide. As she rebuilds her identity now in the big city, she wonders what it would be like to start a new life based on love and respect with Ramrao, a trade union leader who shares her ideologies and dreams.

The following are excerpts from the book.

Appasaheb’s inter-caste marriage had made his family cut all relations with him. He was not a welcome member there and his wife’s family were not welcome visitors in his home. As a result, there could be no small talk between father and daughter. Instead, their walks became an extension of school with Appasaheb taking Kalindi beyond school books into the wider world of knowledge. On one of these occasions when Kalindi had turned twelve, she asked him, ‘Baba, you are a brahmin. Why didn’t you marry a brahmin girl?’

Appasaheb was momentarily taken aback by the question. Had an adult asked him the same question, he might have spoken of social reform and moral courage—ideas which had become the pegs on which he had grown accustomed to hang his action. However, these were not ideas he could spout before his own daughter. To buy time he asked her, ‘What makes you ask?’

Kalindi replied, ‘The girls in school don’t drink water from my hands. They say your father might be brahmin but your mother isn’t. So you are not brahmin.’

To this Appasaheb replied, ‘That is the point, Kalindi. Most people believe in caste. I don’t. That’s why I married your mother.’

Soon after this conversation, Kalindi stopped accompanying him on his walks. She preferred to spend her evenings with her school friends.

Walking alone gave Appasaheb sufficient time to introspect and there was much in his life and actions to introspect about. Kalindi’s leaving home had been an enormous shock to him. It was a time when he would have dearly loved to be able to discuss the problem and its consequences with his wife. But he could not, because that was when he became acutely aware of the mental distance between them. He realized that she was not interested in the social aspects of life. What she wanted and was happy with, was her security and comfort. These she had. The repercussions of Kalindi’s act on their social position and on him personally did not interfere with them.

Looking back, he wondered why he had turned away the only marriage proposal he had received for Kalindi, which probably drove her to the irreversible action of leaving home and living with a married man as his mistress. Had he foreseen this, he would perhaps have given the proposal more thought. What made him reject it out of hand was his fear that if she married a man who was himself an outcast, he would have to give up forever the hope that his children would be accepted in society as brahmins. How could he have given up so easily on this hope? His marriage had been conducted with every legality and religious ritual in place. How then could his progeny be treated on par with children born out of wedlock? If the end for which he had struggled so hard was not to be attained, what kind of a father did it make him to have ruined a daughter’s chances of a married life in pursuit of an impossible dream? Moral courage is a fine virtue to embrace if the end is achievable within one’s lifetime. It appeared to him more and more impossible that Hindu society would ever rid itself of its caste divisions and discriminations. And yet he had rejected his daughter and driven away his son whose only crime was that he tried to make him understand the reason for which she had gone so tragically against social custom. How could he say Satyavrat was wrong? And if he was right, did it not behove him as a father to discuss with Kalindi why she had acted the way she did and treat her with sympathy? Now that his own actions had led not to securing his children’s future but ruining it, why did he still dither to call himself an ass and a criminal of the first order? Was it only because his ego stood in the way?

Appasaheb was at a point in his introspection when he felt acutely the need of guidance by someone who had thought deeply about caste, knew its roots, how deep they went and the chances of its ever being uprooted from Hindu society.

[…]

Ramrao’s childhood was spent in the Varhad region of Bombay Presidency but he grew up in Satar. His father, who had been in government service, had died when he was still a boy. However, he had been able to continue his schooling on his father’s savings. He lost his mother when he was in his final year at school. He came to Mumbai for his college education, just about managing to eke out his father’s savings till he graduated. When it came to studying law, he had to start earning his keep. That is when he found a job as a clerk in Murar Deepchand’s office on a monthly salary of thirty rupees which was gradually increased to seventy-five. It was difficult for him to get his law degree in three years as students who did not have to earn their livelihood did. It took him five years to complete the course.

However, the protracted time he took to do it, along with the fact that he was working in a mill-owner’s office all that time, gave him the opportunity to observe the lives of workers and mull over the lack of ethics in the mill-owners’ business practices. There appeared to be no regulator to lay down ethical principles for businessmen. The sole principle that governed their work seemed to be ‘might is right’. It was each man for himself and if you failed to protect your interests, nobody else would do it for you. Workers had no might so they could never be right. Without might, they had no way to protect their interests either. The only way they could get a fair deal was if somebody else led them. Ramrao discovered the levels of crookery mill-owners were willing to sink to in their greed for profits. He also discovered that the higher the social esteem they came to enjoy, the more the evil means they had employed to get there. They were quick to cut a worker’s pay but the idea that the worker was their partner in business, the one who enabled them to earn their profits, never entered their heads. They found it perfectly possible to eat rich food and live in style while those who toiled at their machines starved and lived in dark, dingy tenements. This made Ramrao’s blood boil.

At the end of those years of rumination, he came to a few conclusions. He saw that the government had very little interest in the welfare of workers. It was firmly on the side of mill-owners. It was not that they did not think they should show consideration for workers and their welfare. Of course, they should. However, if you were proposing steps to achieve this you had to speak in conciliatory tones and not be aggressive or too insistent in your demands. This is how things were to be done. The government is in favour of reforms; but the reforms must fall in line with their programmes. The way to draw attention to workers’ plight then is for you to deliver a lecture on the subject. The government representative then follows up with his own much practised patter. You then show how happy you are with the government’s response. The government also shows how happy it is with you. Not only have you given the government an opportunity to show how sympathetic they are to workers’ welfare, but also to shed a few crocodile tears on their behalf. However, if you want to do real work, demand real rights for workers, the government soon shows you how unhappy that makes them. They decide you are a ‘malcontent’ bent on ‘disturbing the peace’ and charge you with ‘sedition’. If you still choose to work hard and honestly for workers’ welfare, you must be prepared to face two powerful enemies—the government and the mill-owner.