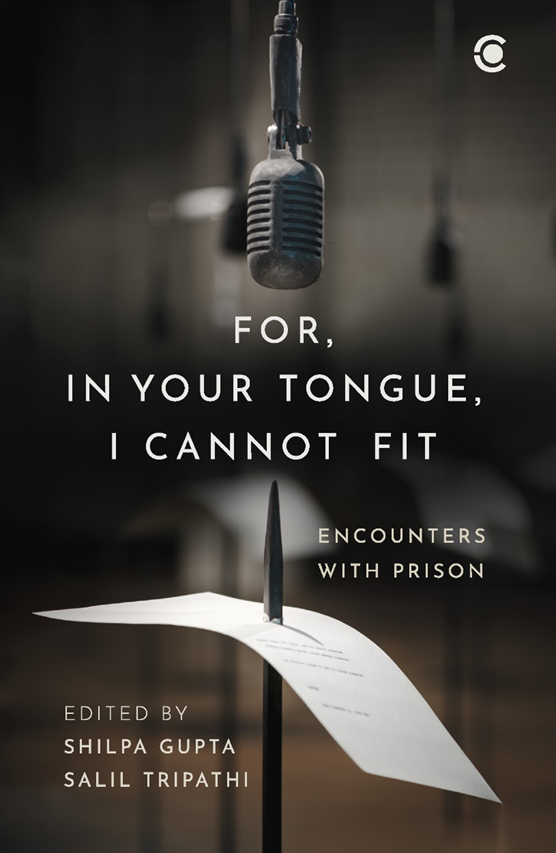

Edited by Shilpa Gupta and Salil Tripathi, conceived in dialogue with artist Shilpa Gupta’s multimedia installation, For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit: Encounters with Prison (Westland Books, 2022) brings together many of the poets featured in the installation—every one of them persecuted for their words. It is an immersive experience, featuring illustrations and images alongside the written pieces. It is also the culmination of an effort of collaboration and support, often under extremely difficult conditions, forming a network that spans countries. The result is an anthology that speaks truth to power and is a testament to the community of words.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

It’s Forbidden to Give Pens to Prisoners, Especially to You

Dareen Tatour

Translated from Arabic by Lauren Pyott

The hours pass slowly in captivity. Cockroaches and bedbugs were my only companions in this cell in the Jalameh detention centre. I tried to keep myself occupied with the insects to distract my ears from the ceaseless sound of the dripping tap, along with my constant heavy coughing. I painstakingly traced their movements on the wall and was deeply moved by the fact that these cockroaches, here in this prison, knew nothing of hibernation or rest. They paid no heed to the place they found themselves in, nor to the cold that surrounded them, and me. These insects moving in front of me were the only sure proof that there was life at all in this bleak cell. Whenever the hours stretched while I was alone in solitary confinement, and I missed having someone to talk to, I looked at these small insects and struck up a conversation with them. That was enough to relieve the burden of my loneliness and keep me from surrendering to despair or frustration.

In prison, every time my sense of alienation intensified, I would redefine the smallest details around me from scratch, probably in a different way to any other prisoner or detainee. I managed to discover a new philosophy of feeling, for prison really does offer a philosophy that triggers the eyes of memory, when the prisoner is a poet or a photographer.

Light always starts from a narrow hole. I summoned these thoughts to create some value and importance to my current life, here in my dark hole, rearranging my mind so I could be reborn with hope and faith. I convinced myself that even if I died after this harsh experience, there could be no doubt that I died for my values and principles.

I sat on the bed with a tentative sense of calm, filled with thoughts of waiting, and unable to do anything but analyse. It was down to me to leave this narrow spot by stealth, through my imagination.

Lots of things written on the wall intrigued me, and I started to read and examine them: various phrases in Arabic, Hebrew and English; the names of people who had passed through here; a picture of a heart; a love arrow with initials; prayers and insults. I would read them – sometimes laughing, sometimes lamenting – and would empathise with whoever had written the phrase. I wished that I had my camera with me to photograph this rare painting, and felt an even stronger need for a pen, and for writing itself.

I asked for pen and paper, but the prison guard refused to give me anything. I tried to understand the reason, her plea that it was prohibited by law here. Immediately I asked her about the writings on the wall, and where they had come from. My reply surprised her and her face bore the shock of my question. I remained quiet and she said again: ‘These are the rules here. It’s forbidden to give pens to prisoners, especially to you.’ She withdrew from the discussion and left without answering my question. I returned to the bed with a volcano of anger at this ridiculous reply, and at the sham of such rules. But at that moment, I suppressed my anger, and a new fact dawned on me that brought overwhelming joy, making me smile. Overcoming anger was a triumph in this moment, and the guard’s retreat from the conversation was a victory of another kind over the system I faced in prison.

More hours passed and all I could do was think, read the writings on the wall, and pray. Prayer too is my sanctuary when I feel the need to speak to someone. I pray to God and speak to Him as though He is in front of me, believing in my heart that there is a message for me to deliver in my detention. This makes me satisfied with everything, and I thank God for that, and wait to find out what the message is behind my detainment and imprisonment. My trust in God and my immense faith helped me contain myself, bit by bit.

My deprivation continued to be one of the most precious things in my life: no pen or paper, a cell in which I lost my dignity by degree, and lived beyond time and place. I reached the furthest point of boredom, frustration, despair and anxiety, and was nearly driven to madness by all that surrounded me. When I started to feel the emptiness of my existence, and the onset of a breakdown, I transformed into a different person. I would rave and talk to myself out loud the whole time, to relieve the pressure of that irritating sound of dripping water. Sometimes I would scream so as to forget, other times I would sing to distract myself from sickness and coughing. Then I would dance and laugh out loud whenever the non-political prisoners approached the door with their cigarettes, exhaling their smoke into my cell in full view of the warden. They would see my indifference and on hearing the word ‘crazy’ from them, I would intensify my singing and dancing and coughing. And the strange thing is that I didn’t cry once, despite all the pain that gripped me throughout the time I was alone.

I reached a point when I could no longer bear this humiliation, this emptiness, this nihilism. My thoughts began to refuse the lifestyle that prison had imposed on me, as well as the conditions of this grey cell. So I found myself evoking memories of bygone days, and would compare what I would have been doing in a similar moment when I was on the outside, to what I was experiencing in this solitary cell, and I would try to focus on whatever I might have been doing then.

I remembered my love for jogging, so I would spend my day walking in the cell, as much as the space would allow, from the toilet to the door, to-ing and fro-ing. Walking like this was how I avoided succumbing to the tyranny of time, or of collapsing into the fatal despair that was taking hold of me.

I would imagine that the grey walls were the road I loved walking on in the streets of Nazareth, leading to the old market quarter. In this way, I would walk up and down in the cell for long hours. The prison guard would approach, stop at the door and ask me: ‘What are you up to?’

But I wouldn’t give any reply and would complete my imaginary tour of Nazareth. She too would cast the word ‘crazy’ at me and leave.

Every time I felt I was an isolated and confined prisoner, I would give myself a talking to, saying: ‘I am a prisoner for the sake of freedom.’ And I would feel that freedom was imprisoned in me too, living and residing inside of me. Whenever I became overwhelmed with feelings of sadness, pain and restriction, I would imagine Freedom as a woman like myself, right in front of me. I would strike up a conversation and would hear her chiding me, saying: ‘You, Dareen, are free.’ I would start to sing to her and to myself, and would hear her respond to my singing, and my voice: ‘Dareen, you are the sound of freedom, can’t you hear freedom’s call? You are the sound of freedom.’ The smaller I felt my cell was, the greater was my freedom.

I sat on the bed and tried to sleep, but couldn’t. I had a severe, unbearable headache and had no option but to ask the prison guard for a painkiller. An hour after my request, she handed me a yellow Acamol pill. I took it and returned to the bed, and quite out of my norm, started to examine the tablet, then rolled it between my palms. Every time I went to swallow it, I would imagine it was a pen, and so reconsidered. Suddenly I had an intense desire to write. A strong urge for a pen overcame me and I could no longer stand myself without writing. All I could feel was my fingers gripping the tablet in an effort to write with it on the wall. My attempt failed, yielding no results. I placed the tablet in my palms and went back to looking at it closely, willing it to somehow release its ink.

I felt a little cold and pulled up the zip on my jacket, then quickly tore it off me, separating the zip, and tried to write with it on the wall. Success. My name, date and time were the first things I wrote. Then my hand inscribed my first prison poem.