Dossier no. 58

![]()

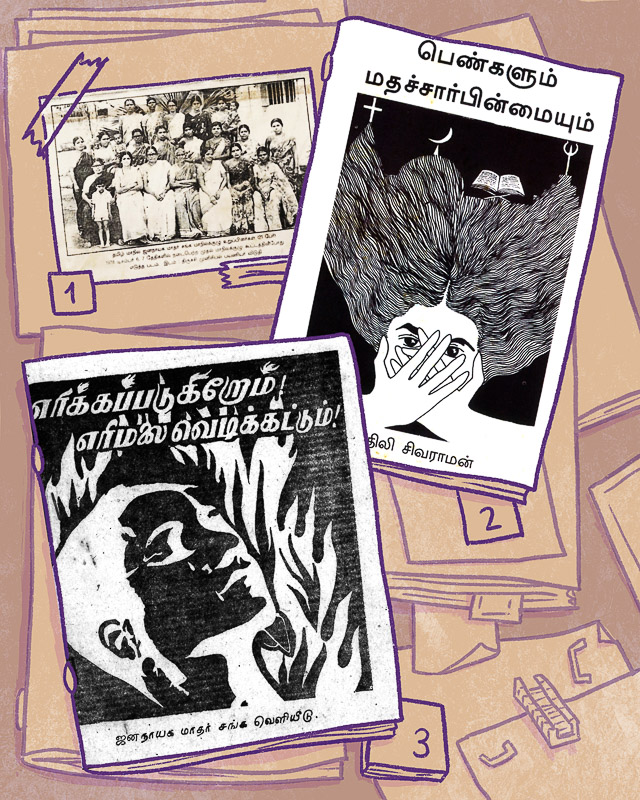

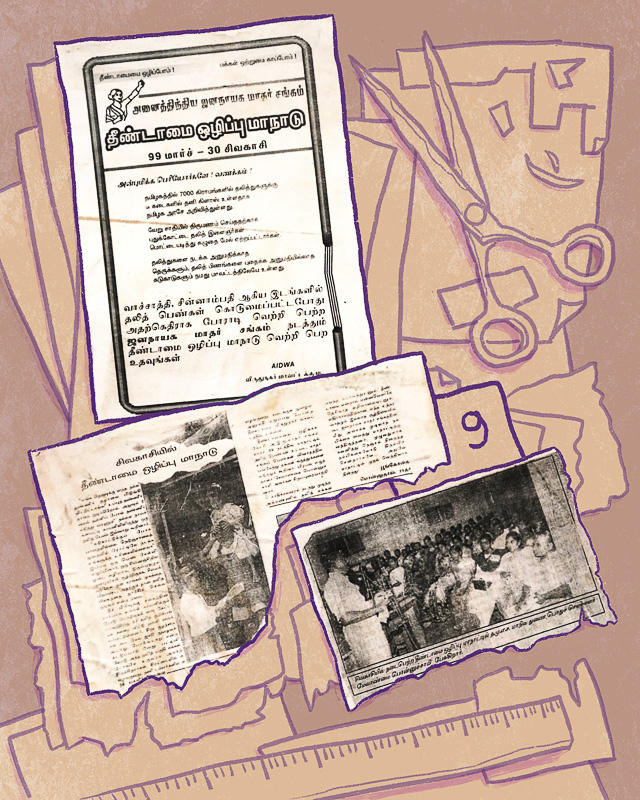

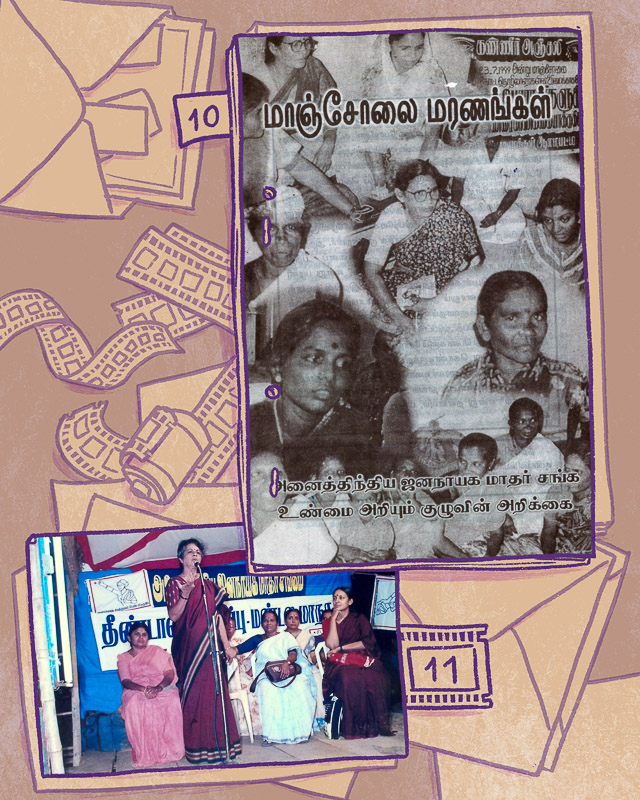

The images in this dossier are compiled in the form of a scrapbook based on ephemera and artifacts from AIDWA’s organising work in Tamil Nadu, India, from photographs of mobilisations and newspaper clippings of leaders to covers of the organisation’s monthly magazine, Magalir Sindhanai. This artwork is an homage to AIDWA’s work and serves as a moment of pause to document, reflect, and recover the collective memory of this struggle in a world in which political and social movements, so enmeshed in the day-to-day work of revolutionary organising, often do not have the time or resources to archive.

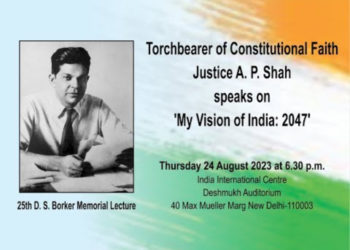

2. Women and Secularism, a book by the former vice president of AIDWA Tamil Nadu, Mythili Sivaraman, date unknown. Source: Archives of AIDWA Tamil Nadu.

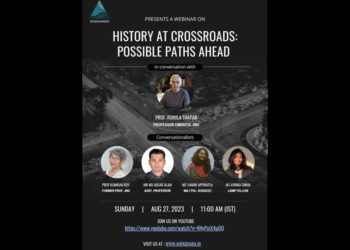

3. The cover of an AIDWA Tamil Nadu pamphlet against dowry murders by burning. The text reads ‘We are being consumed by fire; let the volcano erupt!’, late 1980s. Source: Archives of AIDWA Tamil Nadu.

Introduction

Beginning in the 1960s, Tamil Nadu, a southern state in India with a population of 73 million, experienced an agrarian transformation. This process, brought on by the introduction of new technologies into farming, gave rise to new contradictions while at the same time sharpening the old ones in village society and had a marked impact on the politics of the entire state. During this period, these contradictions manifested in numerous incidents of organised atrocities against oppressed castes as well increased violence against women.

In this context, a group of women activists in the communist movement in Tamil Nadu formed an organisation called Jananaayaga Madhar Sangam (‘Democratic Women’s Association’) in 1973 to address the specific nature of women’s exploitation and oppression. Eight years later, in 1981, Madhar Sangam joined a group of other left-wing women’s organisations from different Indian states to establish the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA).

Leading a range of struggles to mobilise a broad section of women against gender and caste oppression and against class exploitation, AIDWA built a strong organisation that now has over 11 million members. One of AIDWA’s organisational strategies is ‘intersectoral organising’, which focuses campaigns on the specific issues of different sections of women (such as oppressed caste women or Muslim women) and then mobilises its members as well as other mass organisations into these campaigns.1

These struggles are not distinct from each other; together, they are united in building power for women’s emancipation. Such a multi-layered approach demands a continuously evolving understanding of realities on the ground and of the situation of women in all the complex intersections of society (such as caste hierarchies and religious differences). Regular and rigorous grassroots research by AIDWA has become a necessity to grasp these complexities and to better prepare AIDWA for its campaigns.

In the 1990s, India’s neoliberal turn wreaked havoc among the working class and peasantry. Hunger and precariousness heightened social tensions along the hierarchies of caste, gender, and social identity (including religion). Surveys by AIDWA in this period revealed new fault lines in both the countryside and in cities. One of the leaders of AIDWA in Tamil Nadu, R. Chandra, developed many of the organisation’s surveys that looked at changes in the agrarian economy, at caste oppression, and at the specific impact of the rightward drift of Indian politics on Muslim women. During the years these surveys were carried out, R. Chandra served as a state committee member and joint secretary of AIDWA in Tamil Nadu as well as the district president of AIDWA in Tiruchirappalli. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research spoke to R. Chandra about AIDWA’s surveys in particular and activist research in general.

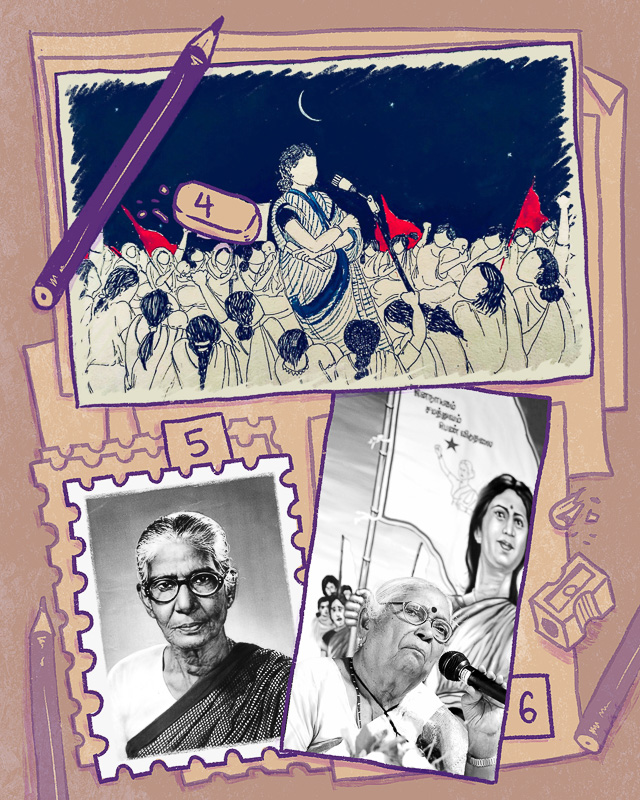

5. AIDWA Tamil Nadu leader, K.P. Janaki Ammal, date unknown. Source: Archives of AIDWA Tamil Nadu.

6. AIDWA Tamil Nadu leader, Pappa Umanath, date unknown. Source: Archives of AIDWA Tamil Nadu.

Could you tell us more about the origin of AIDWA in Tamil Nadu as well as your work in the organisation?

In 1973, women activists in the communist movement founded Madhar Sangam, with comrade Pappa Umanath as its president and K.P. Janaki Ammal (or Amma, as she was affectionately called) as its secretary. Amma, a singer, actor, powerful orator, and freedom fighter who was imprisoned during the freedom movement, is a role model to communists in Tamil Nadu, and Pappa Umanath (who came to be known as Ponmalai Pappa) played an important role in the famous railway strike in 1940s. Together, Amma, Pappa, and others founded Madhar Sangam with three objectives, namely: the emancipation of women (pen vidudhalai), equality (samathuvam), and democracy (jananaayagam). The membership fee was only 50 paise, and any woman could join. Other important founding members were Mythili Sivaraman, Vijaya Janakiraman, Kunjitham Bharathi Mohan, Shazadi Govindarajan, and Janaki Ramachandran. These activists, who were part of the Indian communist movement, felt the need for an autonomous women’s organisation within the umbrella of the larger left movement in India. Together, they mobilised thousands of women and fought for their rights. Both Amma and Pappa visited the downtrodden and took up their issues. Even those women who were initially hesitant to take to the streets and raise slogans joined the movement in large numbers. As Madhar Sangam’s membership gradually increased, women started approaching the organisation whenever they faced problems.

The experiences of Madhar Sangam’s founding members in farmers’, workers’, and a various other mass movements led them to start a movement which would bring the particular issues facing women together with their understanding of how the oppression of women was intimately – although not exclusively – linked to economic exploitation and class contradictions. Madhar Sangam was a broad coalition of women from various strata of society – from agricultural workers to middle-class women – all of whom were fighting for equality and emancipation. The immediate impetus to form the organisation was the rise in violence against women, violence justified by custom. In the 1970s, every day, the Tamil newspapers reported women’s deaths by catching fire in a kitchen ‘accidents’ or by setting themselves on fire with kitchen fuel. Everyone knew that these were dowry murders. Madhar Sangam’s first campaigns were around the dowry issue.

I joined Madhar Sangam in 1977 and became a member of its state committee in 1979, when we largely focused on dowry issues. We fought for justice for the victims and punishment for the perpetrators. We got involved in incidents of dowry harassment, and we fought for proper legislation to prevent dowry murders as well as to sensitise legal institutions about this issue. In 1981, left women’s movements from different states in India, such as Madhar Sangam in Tamil Nadu, joined together to form AIDWA. In the 1980s, we – along with other women’s groups – agitated against the increasing sexual violence against women (including rape) and the lack of legislation that facilitated justice for the victims; we wanted the onus to move from the women to the accused. Under the conditions of Indian society, this was an important and necessary legislative intervention.

While being part of these large struggles, AIDWA actively engaged in struggles in the localities where we are present – such as for drinking water in the summer, for streetlights, for food distribution, and for public buses. These issues were very important to improve the conditions of working-class women and their families. We mobilised on a local level to demand that the administrations provide these facilities. For example, when there were water shortages, AIDWA mobilised women to break their pots in front of the municipal corporation, demanding drinking water. Through these processes, we developed the leadership of working-class and poor women activists. We mobilised at the state level when the price of food and fuel increased, which was felt acutely by women.

8. The cover of an issue of AIDWA’s monthly magazine, Magalir Sindhanai, dedicated to the struggle against the forcible acquisition of farmers’ land for an expressway between Chennai and Salem. The title reads, ‘Not a Green Corridor, but a Green Erosion’, July 2018. Source: Archives of AIDWA Tamil Nadu.

Survey research plays a substantial role in the work of AIDWA in Tamil Nadu. Could you tell us about the state-wide survey that AIDWA conducted on agrarian issues?

In the 1990s, the agricultural sector and rural areas began to acutely feel the impact of the liberalisation of the economy as the state began withdrawing agricultural support. There was a severe agrarian crisis and loss of rural employment as a result of the drastic reduction in bank credit to agriculture, phasing out of extension services that provided technical inputs to farmers, lack of public investments in irrigation, cuts in expenditure on the maintenance of irrigation facilities (canals, reservoirs, etc.), and reduction of agricultural subsidies, coupled with exposure to volatile agricultural markets due to trade liberalisation. Exposure to international markets and the spread of contract farming led to changes in cropping patterns, often moving away from labour-intensive crops. The impact of this crisis was particularly acute on agricultural workers, who, faced with the loss of employment, were often forced to migrate out of distress.

Many AIDWA members are also agricultural workers, so these changes directedly impacted their own lives and the lives of their families. In AIDWA’s district committee meetings, members discussed the patterns that they were witnessing in their communities. For example, at a meeting in the Thiruvarur District, an AIDWA member told us that she had seen a rise in unemployment in her village due to the shift away from paddy (rice) cultivation. In her village, a multinational corporation had leased 300 acres of land from various farmers to cultivate gherkins for export. Prior to being leased out to that company, these 300 acres of fertile land had grown paddy, which is a highly labour-intensive crop. After leasing the land, the company cultivated, processed, and shipped the gherkins, providing employment to just twenty-nine people on those 300 acres. When they were used for paddy cultivation, these 300 acres provided employment for many more people, generating income for the entire village.

I then raised this and other issues at an AIDWA leadership meeting in Delhi. The general secretary of AIDWA at the time, Brinda Karat, listened keenly and told us that we needed to find out more about what was happening to agriculture across the state of Tamil Nadu. That is why we designed and conducted a survey in 1998–99. AIDWA activists carried out the survey in every district except for Tiruchirappalli, where my students assisted me, and I tabulated and analysed the data. The learning experiences in the field provided AIDWA activists with evidence of atrocities that needed to be challenged as well as insights into how to build campaigns to transcend these atrocities.

We began our survey in Thiruvarur, near the coastline of Tamil Nadu, and then moved to Dindigul, in the interior of south-central Tamil Nadu. In our surveys, we detected shifts in cropping patterns and saw farmers move from food grains to more lucrative horticultural crops such as jasmine, papaya, guava, and grapes. In some instances, we were able to identify an increase in child labour caused by these changes; in others, we saw women perform tasks that they had not performed previously.

In the Dindigul District, we witnessed a transition in which decisions that farmers had made previously became subordinated to the whims of companies. We talked to farmers who told us that companies contracted them to cultivate specific crops, in this case papayas. I did not know that papaya extract is used in the cosmetics industry, notably in facial moisturisers and skin cleansers to provide anti-aging properties as well as in hair products. The process to create papaya extract is similar to the process to tap rubber trees for sap. The company provides the farmers with seeds and then sends experts who come from far-off Coimbatore to plant them, cut the stems, and collect the extract. The extraction of papaya essence is very profitable for farmers. One farmer told me that he had completely shifted his five acres from paddy cultivation to papaya extract cultivation. He not only repaid the debt that he had incurred to make this switch; he was also able to send his son to a private engineering college and build a house, all thanks to papaya farming. Farmers who had land benefitted from the change in cropping patterns. However, the decline in employment due to the lower number of people needed to produce papaya extra and due to the reliance upon the company’s own experts meant that social inequality in the area rose dramatically. I wrote about this in Peasant Struggle, the magazine of the communist-led farmers’ movement, All India Kisan Sabha.

The shift in the cropping pattern in Dindigul not only increased unemployment in some instances; in others, it led to the emergence of child labour. When the farmers converted hundreds of acres of paddy fields to grow jasmine flowers, they began to bring in children to pluck the flowers. The children would get up at 3am and rush to the farms, which were about half an hour away, because the flowers had to reach the market in the town of Madurai as quickly as possible to be sold for household and temple use. They picked the flowers until 7am and then went to school. In the time of high demand, such as in festival or marriage seasons, the children would go from their schools back to the farms to pluck jasmine flowers in the evenings. The villagers would send their children to the jasmine farms at 3am, waking them up and sending them along without brushing their teeth or washing their faces. For the farmers, the jasmine, unlike paddy, was a more lucrative crop, and it provided a boost to their incomes. Still, despite the high prices, this was a form of child labour.

It was AIDWA’s survey that revealed the existence of child labour in Dindigul’s jasmine industry. Child labour has been banned in India since at least the Child Labour Act of 1986, while earlier legislation in 1948 and 1952 banned children from working in factories and mines. Nonetheless, at the very least over 10 million children work in India in several hazardous and onerous industries such as diamond polishing, fireworks manufacturing, carpet weaving, and domestic work. There have been many initiatives to end child labour, some of them led by trade unions and others by non-governmental organisations.

So, AIDWA took up this issue in Dindigul because of the survey. When we heard that a child had been bitten by a cobra and killed while plucking jasmine flowers, we approached the district collector (the main state official in the district) and told him that it was his duty to intervene, since child labour was banned and since children must be afforded the right to play and to study. We spoke with the farmers and the parents, trying to sensitise them to the atrocity of child labour. We told the parents not to send their children to work, since they needed to play and study. We got in touch with the teachers at the local school and tried to get them to talk to the parents to ensure that the children went to school. We had some success convincing parents to send their children to school, but the families’ poverty was such that the children’s incomes were of great importance to stave off hunger. Not all of them were willing to let go of this source of income. That was not an issue we could resolve in the short term.

In Viluppuram District, west of Puducherry, our survey showed that there were marked changes in the labour process of sugar cane cultivation. Whereas most of the heavy work – such as carrying the sugarcane bundles and loading them on the trucks – was previously done by men, women were now doing these jobs. When we visited the fields, the women workers told us that they were doing these jobs out of necessity. This backbreaking work was severely damaging to women’s reproductive health, specifically harming the uterus.

While carrying out the agrarian surveys, we found that farmers generally did not want their children to pursue farming as a profession. They would say, ‘I am the last in a line of farmers. I don’t want my children to become farmers’. When we asked them, ‘where is your son or daughter studying?’, they would reply that they were studying at Udumalpet College or this or that engineering college, training to become engineers and doctors – professions other than farming. The National Commission on Farmers (2004–2006), chaired by M.S. Swaminathan, noted that 49% of farmers are leaving their profession. We saw this clearly. In many parts of Tamil Nadu, there is no next generation of farmers.

The changes in cropping patterns that we detected and that were taking place due to the liberalisation of agriculture were very stark. For example, we saw that farmers switched from food crops to non-food crops, which threatens food security and impacts employment opportunities. Despite significant mechanisation and the use of new technologies, paddy cultivation remains very labour intensive. As an economics teacher, I know the problems faced by any producer who relies upon one product or, in the case of farmers, specialises in one crop. Since a failure of that crop leads to great financial loss, putting all of one’s eggs in one basket should be discouraged.

We saw that many families of agricultural workers were forced to migrate due to growing unemployment in rural areas. According to the 2011 Census of India, rural to urban migration increased by 51% from 2001 to 2011, counting 78 million migrants in 2011, 55% of whom are women. Though inter-district seasonal migration that arises out of cropping patterns is common, our survey found that this was not the main cause of migration in this case, a conclusion that was reinforced by census data. What we saw was people migrating for work, which is what we call ‘distress migration’. The AIDWA survey clearly showed the precariousness of rural livelihoods and the government neglect of these issues.

While AIDWA was carrying out this significant survey on the impact of liberalisation on agriculture, the organisation was also conducting a survey on caste oppression and violence. Could you tell us about this second survey?

In the 1980s, AIDWA intervened across the country in women’s struggles against various forms of social oppression. These included not only domestic violence and cases of rape, but also dowry harassment. During the negotiations around a marriage, the groom’s family demands various goods, which – in the era of liberalisation – expanded to include expensive consumer goods. If this dowry is not provided, the groom’s family harasses the bride. It should be pointed out that though the Dowry Prohibition Act (1961) abolished dowries, making them an illegal practice, they are still very common. AIDWA provides legal help to women, deals with the police, fights for justice and redressal in the courts, and works with political forces to improve the legislation on these issues.

By the 1990s, it had become clear that this intervention against social oppression had to focus on specific forms of oppression that impacted different sections of women, such as Dalits (oppressed castes), Muslims, agricultural workers, and young women. At the 2001 AIDWA conference in Visakhapatnam (Andhra Pradesh), at the behest of Brinda Karat and then the general secretary, we took the decision to establish several subcommittees to address the problems and issues of different sections of women. For the first time, AIDWA office-bearers were divided into subcommittees to work on issues faced by women in different sections; we established a Dalit subcommittee, a minority subcommittee, and so on, forming a total of eleven subcommittees over the years.

I was part of the Dalit subcommittee along with K. Balabharathi from Tamil Nadu, who was then a member of the Legislative Assembly from Dindigul. Our first task in Tamil Nadu was to study the prevalence and forms of untouchability and to assess the kinds of discrimination faced by Dalits in the state. At that time, as a state office-bearer of AIDWA, I was also in charge of the Pudukkottai District, which was known for the prevalence of various forms of untouchability. I had only read about atrocities against Dalits in newspapers or watched these incidents portrayed in the cinema, but I had not experienced the wretchedness of it until this task was put before me. I was shocked by their existence and prevalence.

It is hard to describe this wretchedness, the violence of the caste system. While carrying out the survey, there was a story in the Madurai District that really hit us hard. As a Dalit woman was walking along the edge of a paddy field, which was filled with water, a dominant-caste man walked towards her from the opposite direction. He asked her to leave the varapu, the narrow bund that separates one paddy field from another. When she refused, the dominant-caste man beat her up and forced her to drink urine. It is difficult to imagine that such things can happen in our time, in a society that claims to be civilised, but this is exactly the wretchedness of the caste system.

Everything became clear to me in the aftermath of an atrocious event in the village of Themmavur, north of Pudukkottai’s main city. There were 3,000 residents in the village at the time, 500 of them Dalits. Beginning in 1996, Dalits in this town refused to be forced to beat drums during the festivals at the two temples for the goddesses Mari Amman and Kali Amman. The dominant castes, who controlled the town and the temples, insisted that the Dalits beat their drums, which they said was the Dalits’ customary obligation. The Dalits refused, saying that forcing them to do this was an act of humiliation since they were not permitted to enter the temples. The main Dalit community in Themmavur is the Parayars. When the dominant castes tried to force them to beat the drums, young people in the Parayar community said, ‘Alright. We will beat the drums, but would you let us inside the temples to offer Pongal [rice cooked with milk and sugar] to the deities?’. The dignified refusal by the Parayars to beat the drums enraged a large section of the dominant castes, who began a campaign of intimidation, harassment, and violent attacks. On 17 May 2000, the police withdrew from the area, and then the dominant-caste men barged into a Parayar village and went on a violent rampage. Because it was festival time, most Parayar households had relatives with them in their homes. They had stored food grains and made a range of preparations for the celebration. The dominant-caste men chased and beat people, destroyed their grains, and damaged their homes, which were mostly thatched huts. Parayar women were beaten with great violence.

The Pudukkottai AIDWA unit called me right after the violence, and I decided to go there since I was in Tiruchirappalli (an hour or so away). The policemen were not allowing anyone into the village, so I told them that I was a professor and a researcher and that I needed to get inside; this was true, since I was teaching economics at the Urumu Dhanalakshmi College. That’s how I was able to enter the village. As soon as I entered, I saw bloodstains all over, evidence of the harsh violence. The Parayar village was destroyed, people were seriously injured, and many were taken to the local hospital. One Parayar woman had to undergo a hysterectomy after the dominant-caste men attacked her, pushed to the ground, and stood on her stomach. The dominant-caste men did not spare the children, breaking the girls’ ribs and destroying their toys.

I went to the village with AIDWA’s Pudukkottai District Secretary Siva Banumathi, activists Noorjehan and Rukmani, and the local CPI(M) unit. We learned that the police had refused to file a First Information Report (FIR), which would have opened an investigation. We spoke to the superintendent of police and the district collector and forced them to file the FIR, all while AIDWA produced our own report on the incident. We followed up on the case for months, fighting to get the victims compensation for their injuries and the destruction of their property. Pursing this case was a real eye-opener for me.

After this, similar incidents of violence in Pudukkottai came to our attention. In one case, dominant-caste men urinated in a well in a Dalit area. The police refused to file a FIR, a refusal that has become increasingly commonplace. It was in this context, from these experiences, that we felt the need to create an organisation to gain a comprehensive understanding of the various forms of untouchability and discrimination faced by Dalits. We felt that a survey of Dalit households was necessary. So, we assembled a team of researchers, most of whom were AIDWA activists. They were district and taluk (local level) office-bearers as well as women activists from the state’s Dalit communities. We came up with a structured questionnaire and a methodology for the process, which we designed with the help of Professor Venkatesh Athreya of Bharathidasan University. We divided the state of Tamil Nadu into four zones and drew all of the major office-bearers from AIDWA into the survey work. We organised workshops to train the activists to conduct the survey. Getting the questionnaire filled out was not easy, since untouchability and the oppression of Dalits, while prevalent, are often denied and are seen as sensitive issues. The Dalit respondents were often fearful of talking openly, while the non-Dalits were not candid about the situation. So, activists who went to get the questionnaire filled out had to be trained on how to obtain information without necessarily asking direct questions in case the respondents refused to participate.

We conducted the first round of surveys in the southern area of Tamil Nadu known as the south zone. We were able to cover various regions including Dindigul, Madurai, and Pudukkottai. We held a zonal conference in Pudukkottai to present the results and to discuss them with those who had worked on the survey as well as the various political leaders of our movement. We identified a number of cases of untouchability and discrimination in every taluk (locality). In villages that had a substantial population of Dalits, we found that they were not allowed to enter the local temples, even during festival days and special occasions when devotees traditionally offered Pongal to the deities. In some villages, Dalit children who wanted to go to temple to offer prayers to the deities during the time of exams or after they had done well in their exams were forcefully prevented from doing so. We realised from the survey that for the Dalit communities, entry into the temples is a major issue.

Similarly, in almost the entire south zone, the cremation or burial of the dead was a serious concern for Dalit families (some Hindu customs dictate that young children should be buried, not cremated). In Coimbatore, a major city in western Tamil Nadu, there is an area called Ganapathi where Dalits have no place to cremate or bury their dead. I still remember the heart-wrenching story of a young mother in the district of Thanjavur who had lost her child. It was in November, during the monsoon season, and so it was raining heavily. The family of this young woman was living on the banks of the Kaveri River. Because they are a Dalit family, they faced discrimination from the dominant castes who would not permit them to bury their child. They pleaded with the local government officials to help them, but nobody bothered. They were finally forced to bury their child on the riverbank, near their home. It was raining heavily. Over time, the earth that covered the body eroded, leaving it exposed. The mother told us that she saw her child’s body being eaten by dogs. How can one even react to such an atrocious sight? It was so terrible. And this was not the only story like this. We understood that this was also an issue that needed to be taken up in our political work.

11. R. Chandra presents the report of AIDWA’s survey at the organisation’s Untouchability Eradication Conference of the South Zone in Pudukkottai, Tamil Nadu, 26 July 2002. Source: Archives of AIDWA Tamil Nadu.

One of the most well-documented forms of social oppression is the so-called ‘three-glass system’ that is used in tea shops and in restaurants. The owners who practice this atrocity use glasses made of aluminium, brass, and glass that are used to serve tea to people from different castes. Dalits and other oppressed castes are made to sit in a separate part of the shop and are served tea in a distinct kind of cup. I remember an interaction with the owner of a small tea shop. I asked him, ‘How do you know which of the three glasses to give a person?’. He said that his shop has practiced this system for a long time and that they are able to identify who comes from which caste because they know most of the people in the area. I asked him to identify my caste. He said, ‘Maybe you are from Kerala. Your Tamil has a heavy Malayalam accent’. I said, ‘I am not from Kerala’. To which he replied, ‘Maybe you are… I can’t identify your caste’. When I asked him how he is able to identify who is or is not from the Dalit community, his reply interested me: ‘If they are outsiders, we look at the caste of the family with whom they go to stay. From that evidence, we know who is or is not a Dalit’.

Caste hierarchies and discrimination are so ingrained in our society that even within the oppressed castes, distinctions are reproduced. The Pallars and Parayars – both part of the Dalit community – do not accept the Arunthathiyars as equals and avoid eating with them. These practices must be removed root and branch, requiring a great deal of struggle. This struggle must be based on the most accurate information. That is the role of surveys in our movement.

At the heart of discrimination against Dalits is the question of land. Our surveys found that nearly 95% of the Dalits we spoke to did not own or have control over land, even in villages where they make up the majority of the population. Because of this, they have to sell their labour power as agricultural workers on other people’s land, and they are dependent on the landed dominant-caste families for survival. One consequence of this dependence is that the moment Dalits resist forms of social humiliation (such as practices of untouchability), which are used to reproduce social and economic hierarchies, the dominant-caste families cut them off from work. In other words, the dominant castes use their economic power to maintain their social authority, and they use their social power to ensure the longevity of their economic dominance. For instance, when Dalits in Themmavur refused to beat the drums at the festival, they faced a range of attacks by the dominant castes. Though AIDWA ensured that the government compensate them for the loss of their property, the dominant castes made sure that they lost their livelihoods. ‘Fine’, they told the AIDWA team, ‘you came and helped us to get back what we lost, but now the Chettiars and others [the dominant castes] are not letting us work on their fields’. They were forced to travel to Thanjavur and other neighbouring districts for work.

After we completed the surveys, we organised and tabulated the data from each district, keeping track of each detail that we came across. Then, we held four zonal conferences where we presented a preliminary report and discussed the issues that we had encountered. Based on our survey and on data from the National Human Rights Commission of India, we found that every hour, two Dalits are attacked somewhere in India, and every day, three Dalit women are raped, two Dalits are killed, and at least two Dalit homes are set on fire by dominant castes. Many of the delegates to these conferences recounted their stories. For instance, Jayam, the president of the Kilvelur panchayat (local self-government) in Thiruvarur, reported that a panchayat clerk who comes from a dominant-caste, landowning family refused to work under her. We were also told how drunk mobs from the dominant castes in Perambalur attacked Dalit settlements during religious festivals. AIDWA Assistant Secretary K. Balabharathi, who is also the Legislative Assembly (MLA) member in Dindigul, said that there was less anti-Dalit violence in the districts of Nagapattinam and Thiruvarur largely because of the impact of the struggle for social reform and economic rights organised by All India Kisan Sabha and the communist parties. The role of the left in these areas indicated the importance of leading such struggles for emancipation.

In May 2007, because of the work of AIDWA and All India Kisan Sabha, left organisations created the Tamil Nadu Untouchability Eradication Front (TNUEF). Following the AIDWA survey, whose final report we published in our monthly magazine, Magalir Sindhanai, TNUEF conducted its own survey in 1,845 villages in 22 districts in the state, which found 82 forms of untouchability and 22 other types of atrocities against Dalits. One of these forms was the erection of a wall to divide dominant-caste areas from Dalit areas. This survey, like the AIDWA survey, provided the means for people’s organisations to focus attention on those aspects of oppression that most troubled the people and to pursue these cases through police stations and courts. In 2008, TNUEF galvanised the people of Uthapuram (in the Madurai District) to abolish one of these caste walls. Prakash Karat, the Communist Party of India (Marxist)’s general secretary at the time, participated in breaking that wall.

In addition to the surveys on agrarian and Dalit issues, we also carried out a survey in each district in Tamil Nadu about the reality facing Muslim women overseen by comrade Ramardam, who led the minority subcommittee. The survey found that Muslim women do not receive adequate education, nor do they do have access to proper health care or employment opportunities. Following the survey, we held meetings with Muslim women and formulated a series of demands that were specific to them, demands on which AIDWA then campaigned. Out of these kinds of surveys and activities, AIDWA organised the National Convention of Muslim Women in August 2008.

Could you reflect on the role that the surveys have played in AIDWA’s politics?

The surveys have helped AIDWA develop a thorough understanding of the social and economic landscape. Through the surveys on caste oppression, we were able to identify different forms of untouchability that were being practised. AIDWA activists then took up these issues and mobilised at every level to fight against them. In the process, many women who joined in these struggles became members of AIDWA. The survey and the struggles that they generated deepened AIDWA members’ understanding of the reality of caste oppression, and they forced us to ensure that at least one Dalit woman holds office in every AIDWA committee. During this process, Dalit women entered different levels of leadership in the organisation and further improved our understanding of and work against caste oppression. This was highly positive.

The experience of the surveys on untouchability and agrarian issues taught AIDWA to make research a priority. The practice of carrying out a survey before taking up an issue has become ingrained in our work. We have developed a concrete methodology for sampling and properly structured questionnaires. In Tiruchirappalli, AIDWA’s district committee members and block committees led the survey process, and then AIDWA assessed the survey results, began to campaign on issues based on our findings, and ensured a resolution for people experiencing dowry-related issues.

Whatever the problem may be, when you meet the officials who are expected to redress grievances, they ask you for data. It is always good to do area-specific, issue-specific surveys before going forward with your demands. Whether or not the officials do anything about it, they will at least be aware that such issues exist. Through this process, activists also get a qualitatively better understanding of the situation. For example, people complain that there is no fixed-price ration shop in an area, no government shop – in other words – to provide subsidised food and cooking fuel. AIDWA activists quickly carry out a survey to find out how many households would use a ration shop in that area. Then, with the data, we approach the Civil Supply Authority that would set up such a shop with this information and petitioned for such a shop. This puts pressure on the state to take action.

AIDWA’s members no longer need a professor to help them. They formulate their own questions and conduct their own field studies when they take up an issue. Since they know the value of the studies, these women have become a key part of AIDWA’s local work, bringing this research into the organisation’s campaigns, discussing the findings in our various committees, and presenting it at our different conferences. This sharing of information inspires other organisations to replicate these activist research practices.

AIDWA’s objective is to change the socioeconomic character of society. AIDWA is unlike any other women’s organisation or club in the country. For example, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that works on the issue of female foeticide might seek to better implement the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act of 1994, but it would be limited both by the law and by its single-issue approach. AIDWA has a different perspective. We are not defined by one or two issues, such as female foeticide, even as we take up this issue across the country. In 2005, AIDWA conducted a survey in Haryana that revealed the stark reality of violence against women. High dowry rates, the survey found, are a key reason for sex-selective abortions. Even though there is a disparity between the number of men and women in society, men continue to dominate in the practice of selecting a marital partner, even using brokers to bring women in from outside the state. AIDWA’s survey led us to carry out a campaign against dowries that fights to reduce the financial expenditures at weddings and to prevent dowries from being paid; we seek to appreciate and honour families with girls, making an effort to organise girls to assert their own rights. The survey’s results also led to AIDWA’s campaign against the demeaning portrayal of women in our culture. A campaign against female foeticide must also be a campaign against the patriarchal views of women and against dowries; it cannot only be a legal fight, since the real battlefield is in our society. What is unique about AIDWA is that we work with a broader social, economic, political, and cultural framework than an NGO, whose ambit is sometimes limited to making appeals to the state. We want women to be the subjects of their own history, and we want the various social hierarchies that divide us (such as caste and religion) to be highlighted in our common struggle to transcend the hideousness of the present.

13. The cover of an issue of Magalir Sindhanai featuring images of activists marching against violence and liquor and the slogan ‘Let the streets tremble and freedom be born’, December 2019. Source: Archives of AIDWA Tamil Nadu.

Notes

1. For more on intersectoral organising, read study no. 2 in the series Women of Struggle, Women in Struggle by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research: https://thetricontinental.org/studies-feminisms-2-kanak-mukherjee.

Bibliography:

Armstrong, Elisabeth. Gender and Neoliberalism: The All India Democratic Women’s Association and Its Strategies of Resistance. New Delhi: LeftWord Books, 2021.

Chandra, R. and Venkatesh Athreya. ‘The Drumbeats of Oppression’. Frontline, 10 June 2000. https://frontline.thehindu.com/other/article30254173.ece.

Djurfeldt, Göran, Venkatesh Athreya, N. Jayakumar, Staffan Lindberg, A. Rajagopal, and R. Vidyasagar. ‘Agrarian Change and Social Mobility in Tamil Nadu’. Economic and Political Weekly 43, no. 45 (8 November 2008). https://www.epw.in/journal/2008/45.

Karat, Brinda. Survival and Emancipation: Notes from Indian Women’s Struggles. New Delhi: Three Essays, 2005.

Kranz, Susanne. Between Rhetoric and Activism: Marxism and Feminism in the Indian Women’s Movement. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2015.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. Kanak Mukherjee (1921–2005): Women of Struggle, Women in Struggle. Feminisms no. 2, 8 March 2021. https://thetricontinental.org/studies-feminisms-2-kanak-mukherjee/.