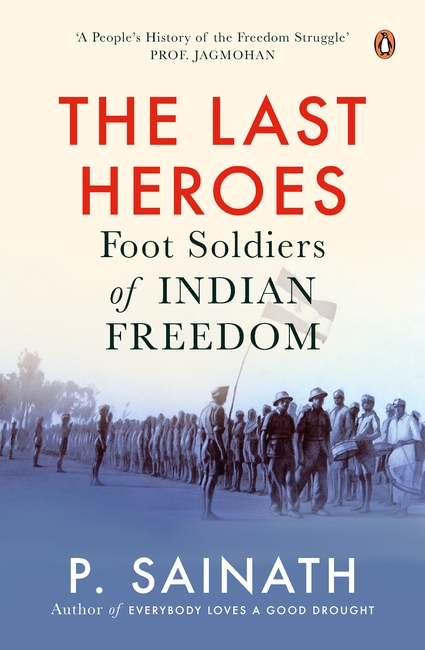

In The Last Heroes: Foot Soldiers of Indian Freedom (Penguin Random House, 2022), P. Sainath, the force behind the People’s Archive for Rural India (PARI), narrates the stories of Indian freedom fighters ignored by official histories. Based on extensive interviews with surviving freedom fighters and their families, the book commemorates 75 years of independence in a way that students and academics would equally find appealing.

Sainath’s book does not just recognise all those who contributed to independence. It is also about how people have changed because official histories erased the ordinary champions of the freedom movement and the selfless dedication they epitomised.

The youngest in this book is 92, and the oldest is 104, so it is the last chance for these unsung footsoldiers to share their stories with the world. Sainath features Adivasis, Dalits, OBCs, Brahmins, Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs—not the select few who can be made into pawns of history and heritage by a divisive State.

In The Last Heroes, freedom is not a gift of a few individuals with innate talents, even less an accident of history. It is, above all, about the cooperative effort people undertook to reshape India’s politics and redefine its priorities.

The following are excerpts from the book.

Who Were Our Freedom Fighters?

Demati Dei Sabar ‘Salihan’ was not a freedom fighter. Not to the government of India, anyway. Yet, when barely sixteen, this Adivasi girl led a spectacular counterattack on a British police force raiding her village in Odisha. She and forty other young tribal women took on a platoon of armed police with only lathis—and won.

She did not go to jail. She was not a part of organized politics. She had no role in campaigns like the Civil Disobedience or Quit India movements. In the village of Saliha, where she led that death-defying charge, they still speak of her valour. In the same village, the names of seventeen people are inscribed on a monument to the uprising. Her name is not among them.

The government of India would never accord Salihan respect as a freedom fighter.

This book does.

In the next five or six years, there will not be a single person alive who fought for this country’s freedom. The youngest of those featured in this book is 92, the oldest 104. Newer generations of young Indians will never get to meet, see, speak or listen to India’s freedom fighters. Never be directly told who they were, what they fought for.

In the seventy-fifth year of Indian Independence, most books, especially those for younger people, mainly focus on the names of a few select individuals as having brought this nation into being. There are still some fine textbooks around that do look at the struggle for freedom and Independence in a sensible and explanatory way. But those are being savaged and rapidly replaced in state after state with appalling fabrications that don’t qualify as history, let alone as textbooks.

In the political and public domain today, the freedom struggle itself is being dated back 800 years. That kind of retelling of India’s fight for freedom gives fiction a bad name. Meanwhile, those who fought for that freedom are vanishing. As many as six of those who feature in this book have died since May 2021. But some of the others whose stories appear here are very much alive and around. Sadly, that can’t be for more than a few years. With the exception perhaps of Mallu Swarajyam and H. S. Doreswamy, these fighters have not featured as major characters in any books. Certainly not in schoolbooks, or in books for a young generation set to lose a national treasure.

When Demati Dei ‘Salihan’ Took on the Raj

She clutches at the once-colourful, now decaying piece of paper that a family member produces at her command. Salihan hands it to us to read, without a word. For Salihan herself can neither read nor write.

The Sabar people have endured a long history of oppression and discrimination. And their literacy, numeracy and presence in schools remain poor even today. That ill-treatment, historically, was not confined to the economic sphere. The deity we now know as Lord Jagannath actually had humble tribal origins with the Savar or Sabar people who worshipped him as ‘neela Madhaba’.

‘The deity was appropriated centuries ago by powerful upper castes,’ says Fanindam Deo, historian and former principal of the Khariar Autonomous College in Nuapada district. And by the nineteenth century, he says, the Sabar found themselves barred from entry to the Jagannath temple at Puri. Lord Jagannath was by then ‘in the grip of a raja– brahmana [royal elite–Brahmin] nexus.’ A list issued by the Brahmins controlling the temple had banned the entry of ‘bird eaters’ on its premises. The forest-dwelling Sabars, points out Professor Deo, obviously fell into that category.

This is a tribe living with that historic loss of their god and subsequent decline in status over a thousand years. As the British appropriated the great timber wealth of Odisha, tribes like the Sabar—who relied on the forests and did very little agriculture— saw their world crumble. They and other Adivasi groups were terrorized and increasingly denied access to their own forests.

In 1929 and 1930, the cruel imposition of a timber or ‘wood’ tax harassed the forest dwellers further. Together with the gochar or grazing tax, says historian Jitamitra Prasad Singh Deo in Khariar, this was to prove both a major source of discontent, and of mass mobilization, for the Civil Disobedience stir and the Salt Satyagraha in this area. Which increasingly took the shape of a ‘jungle satyagraha’ in a landlocked region without salt. ‘National political cyclones,’ he says, ‘saw winds of unrest sweep Odisha as well.’

There was also the pandhri or pandhari tax—an entry tax (something like octroi) levied on anyone coming into the Khariar zamindari. This, along with the abkari (excise), forest and police administration, had been taken over by the British in the 1890s.

It was in this larger context of ferment and turmoil that not just Saliha but several other villages in the Nuapada–Khariar region erupted, says Singh Deo (who is also the former ruler of the erstwhile Khariar zamindari). And the timber and gochar taxes were crucial issues in a protest meeting held in Saliha and attended by people from other villages as well. There, says Singh Deo, a resolution was passed not to pay the taxes and to resist their imposition. That fateful meeting was held in Saliha on 30 September 1930, the day of the attack on that village by the British.

That was also the day Demati Dei Salihan entered the hearts of her people, but never their history books.