Seema is sitting with her head on the chair. She is tired from all the travelling, that included walking for kilometres, it took for her to reach Jantar Mantar. The 35-year-old from Uttar Pradesh’s Gorakhpur came to attend the massive protest held at Jantar Mantar on November 21.

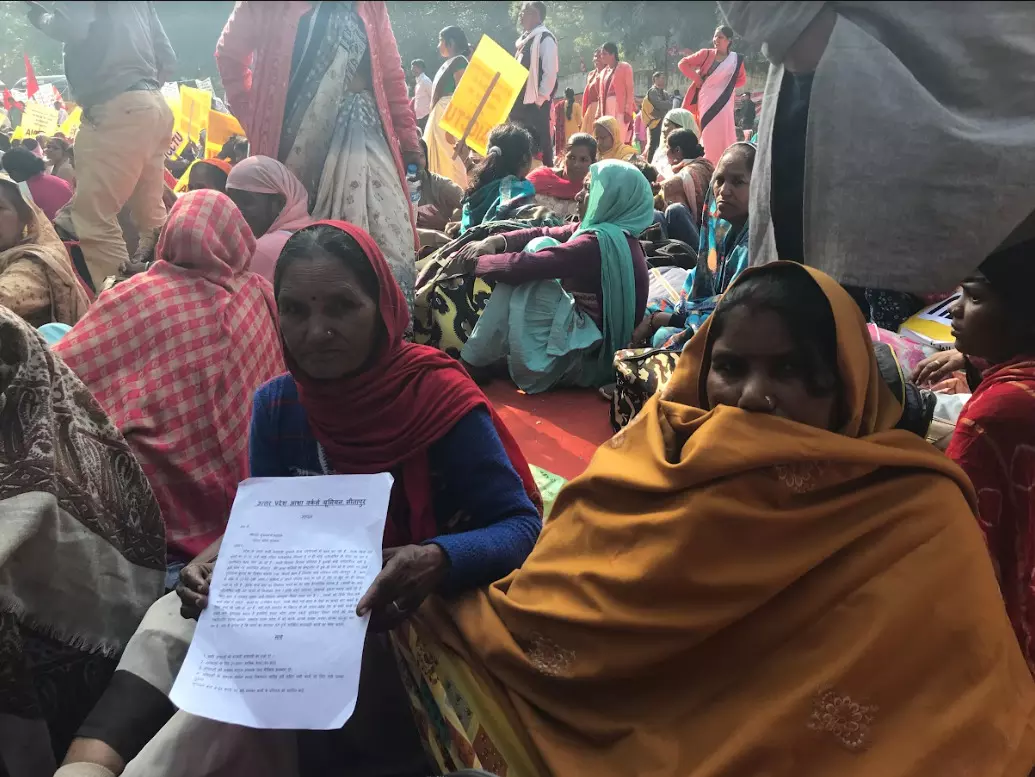

Over 1000 ASHA, Mid-Day Meal, and Anganwadi workers protested at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar against their low income and instability in employment. The workers, mostly women, travelled from all over the country to attend the protest and give a memorandum to the Central government on their list of demands.

Speaking to The Citizen, Purvanti who had also travelled from Gorakhpur narrated her ordeal and said, “we don’t even get paid equal to the amount of work we do. The kind of work we are doing, we should not get less than Rs. 20,000.”

Purvati has been working as ASHA for the past eight years. “We get paid Rs. 2000 for the amount of work we do. This does not include health benefits or travelling costs. And no matter how much work we do, the amount does not go beyond Rs. 3000,” she added.

Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) are an all-women healthcare workforce that acts as the interface between communities and the public health system in India. Even though they are known as “health activists” according to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, their struggle to be recognised as frontline workers and receive access to basic necessities has been ongoing for a long time. “We worked a lot during Covid and got nothing for the work we did. We were out during that time,” Purvati said, “our work goes on 24X7.”

The ASHAs at the protest also said that despite repeated protests and demands, the government has refused to acknowledge them. They are demanding a minimum wage of Rs, 28000, recognition as healthcare workers along with health benefits. Their demand also includes a compensation of ₹5 lakh to the kin of the scheme workers in case of death during the service period.

Meera Devi, who is in her late 30s said that during covid they were not even provided with basic necessities such as Personal protective equipment (PPE) and masks. “To get PPE kits and masks we had to protest and that is when we got it. So many of us got health issues but we still kept working and continue to do so,” she said.

According to an Oxfam India survey released in September 2020, 75 percent of ASHAs were given masks, 62 percent were given gloves, and only 23 percent received full bodysuits. Per the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, ASHAs were meant to receive face shields, masks, gloves, head caps, and sanitiser; in reality, however, they have to struggle with these amenities on their own.

The women are angry and upset as no one is paying any heed to them despite all their struggles, which is why they decided to protest in Delhi. “There is no one to hear from us. It feels like the government does not even have an ounce of sympathy for us. If we get sick on the field, there is no one to listen to us. Even if we die, nobody will listen to us,” Purvati added.

The protesters have listed a set of demands that they will give to the government.

Speaking about it, Shabana, who hails from Gorakhpur and had come to attend the protest said, “Our demand is Rs. 20,000 to Rs. 25,00. We also want health and life insurance. We also want to be recognised as healthcare workers. We also want a time limit to our work. There is no time limit for our work and we can give duty anytime.” Visibly upset with the system, she said that they have to leave the house at short notice.

An ASHA is a resident in the community trained and deployed to improve the health status of the people by securing their access to healthcare services. Her job responsibilities are three-fold including the role of a link-worker (facilitating access to healthcare facilities and accompanying women and children), that of a community health worker (depot-holder for selected essential medicines and responsible for treatment of minor ailments), and of a health activist (creating health awareness and mobilising the community for change in health status).

An ASHA’s performance is based on her assessment of the services after which she receives points. 50-year-old Amarjeet Kaur, travelled from Punjab’s Mansa for the protest. Complaining that even though they work from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. their time can extend, for which they only get Rs. 3000.

“At times we have to go in the middle of the day if there is delivery or anything urgent. If we get sick due to work, we are not even looked at and have to handle everything,” she said.

Meanwhile, the anganwadis provide meals each day to the slum children under 6 years old but also provide lessons in health and hygiene and literacy in a nurturing preschool environment.

The scheme workers also alleged that many ASHAs lost their lives while performing their duties during the pandemic, but their families have not received any compensation so far. They are regularly mistreated in dispensaries and hospitals.

Speaking about the issue, Shashi Yadav, National Coordinator at All India Scheme Workers Federation said, “The scheme workers who had died during covid while on duty, the government had promised a compensation, which has still not been given. We demand that they be compensated.”

She said that there has been no response from the government regarding their demands, but they will continue to protest till all demands are met. “We have made a memorandum, which we will give to the government and we are also protesting. If the government fails to listen to our demands, then after leaving Delhi, we will continue with an indefinite strike countrywide. We want the government to meet us,” she said.

Yadav said they are also demanding a gender cell to be established for scheme workers who have to go through humiliation at times. “The government sees them as bandhua mazdoor (bonded labour). They give us assurance, money will be given, but do nothing in the end,” she said, adding that they will continue a nation-wide protest.

The protest has started taking nationwide momentum with Anganwadi workers from different parts of the state staged a demonstration in Bhubaneswar on Monday and launched a dharna near the state Assembly building ahead of the winter session of the Assembly.

The Anganwadi workers are demanding that they must get the tag of government employees and monthly remuneration of ₹18,000 for Anganwadi workers and ₹9,000 for their assistants. Jhunupama Satpathy, secretary of All Odisha Anganwadi Ladies Workers Association said, “after holding a massive demonstration of 50,000 women anganwadi workers on Monday, we are sitting on indefinite dharna from today. Around 500 women sat on dharna today. Our counterparts in all the 314 blocks are also staging agitation near Block offices.”

Claiming that the state government’s flagship programmes like Mamata Yojana and Harischandra Yojana became successful due to Anganwadi workers, they said that their demands have remained unfulfilled.

According to reports, in 2018, Supriya Sule, a parliamentarian from Maharashtra’s Nationalist Congress Party, introduced a private member’s bill in the Lok Sabha for the welfare of anganwadi workers and helpers. One of the key components of the bill was the regularisation of their jobs. This bill, too, made no further progress in Parliament. In fact, in 2019, women and child development minister Smriti Irani made it clear in the Lok Sabha that the Centre had no plans to regularise anganwadi workers.

The Supreme Court, in April this year, raised serious concerns over the treatment of Anganwadi workers and helpers. A bench of Justices Abhay S. Oka and Ajay Rastogi ruled that the Payment of Gratuity Act will be applicable to Anganwadi centres, something that has been denied to these workers for close to five decades. Observing that it was time that both the Union and state governments “find out modalities in providing better service conditions for the voiceless commensurate to the nature of job discharged by them,” the apex court held that the workers should be paid gratuity and given the rightful recognition of being employees.

Seven months have passed. The Supreme Court judgement is yet to be honoured.

“This government is adamant to not listen to us,” Meena, an anganwadi worker from Bihar said.

Mid-day meal workers from different parts of the country have also averred that they would continue the protest if their demands are not met. The scheme workers in Punjab and Shillong have been protesting on the matter for a week and have threatened to continue it if they are not heard.

The workers have demanded enhancement of their monthly salary from Rs. 100 to Rs. 2000 per month in Shillong. Speaking about the wage discrepancy, Sohila Gupta, leader of a Bihar workers sangathan said that mid-day meal workers in Bihar only get Rs. 1650.

“In times like this, Rs.1650 is nothing. This money is also cut if the workers take a day or two off. On top of that this money is not even given to them on time,” she said.

The cook-cum-helpers hired under the midday meal scheme receive a monthly “honorarium” of Rs 1,000 for 10 months a year to prepare and serve the meals at government and aided schools and do the cleaning up later. The daily minimum wage varies between Rs 200 and Rs 600 across the states.

The Centre and the states share the expenditures under the midday meal scheme in the ratio of 60:40. The Centre therefore pays Rs 600 out of the Rs 1,000 monthly honorarium.

Every government, including the UPA government, has used the term “honorary worker” for midday meal workers. The honorarium was last revised in 2009. At the 2013 Indian Labour Conference, the government had promised to increase the wage.

“Three years back as well, we were given assurance about better pay by the current regime. However, this government only believes in doing jumla, which we can clearly see. Not even a rupee has increased for mid-day meal workers,” Gupta added.

According to reports, there are nearly 25 lakh cook-cum-helpers (CCHs) engaged in the scheme, which is now known as PM Poshan. About 90 per cent are women, mostly single women and widows. “The work of a mid-day meal worker is not just confined to food. They also clean schools and have other responsibilities,” Gupta further said.

Protests were also observed in Manipur, Punjab, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Shillong. The scheme workers say their demands have been ignored and they feel helpless. “We wanted to do this work, but we also wanted respect. We want better pay and health benefits for ourselves and our children,” Seema Devi, who hails from Uttar Pradesh and has been working as an ASHA for the past six years, told The Citizen.

All Photographs Nikita Jain