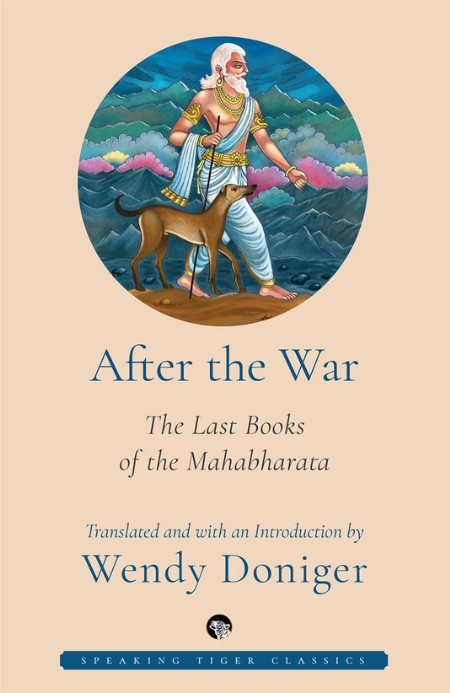

Translated by Wendy Doniger, After the War (Speaking Tiger, 2022), is a new translation of the final parts of the Mahabharata. Composed sometime between 300 BCE and 300 CE, the Mahabharata‘s 75,000 verses narrate the legendary battle between two branches of the Kuru clan of North India, the Pandavas and the Kauravas, and its aftermath. Storytellers in all of South Asia and far beyond have entertained and instructed through this greatest of epics for generations past. But, as the translator says in her introduction, they have generally ‘underra[ted] the high emotion, mythological inventiveness, metaphysical complexities, and conflicted characters that animate the last books [which]…tell a unified and self-bounded story of their own’.

In Book Fifteen (Ashramavasika, Living in the Hermitage) a wild-fire consumes Kunti, King Yudhishthira’s mother, and Dhritarashtra and Gandhari, the parents of the Kauravas, living out their final days in the forest. But did they die a meaningless death? Fate catches up with all, even gods, in Book Sixteen (Mausala, The Battle of the Clubs), when Lord Krishna embraces death and his Yadava clan is annihilated in a drunken brawl and an attack by bandits, in fulfilment of Gandhari’s curse. It is time for the Pandavas to ascend to heaven, in Books Seventeen (Mahaprasthanika, The Great Departure) and Eighteen (Svargarohana, Climbing to Heaven), but not before Yudhishthira is tested by a dog, to ascertain his steadfastness in the moral law.

The following are excerpts from the book.

The Meaning of the End of the Story

Death and Transfiguration

This is the story of people who survived the great disaster and couldn’t bear to go on living any more, when their friends and family were gone. Nilakantha describes them as ‘those who have done what was to be done, but have been swallowed up by unbearable unhappiness’. Particularly poignant is the mourning of parents—and, more particularly, the mourning of women, especially mothers who have lost their sons and husbands in the war. The ease with which so many people in the Mahabharata leave their lives on earth is explained by the prospect of what it is they believe they are going to. This vision of an afterlife is, as we have seen, complex, morally and mythologically rich, theologically deep, messy, inconsistent—in a word, full of life. What distinguishes heaven from life on earth is primarily the higher ethical code of its inhabitants, which might imply that a person who wants to get to heaven should try to live by that code on earth. Nilakantha states that Vyasa’s aim was ‘to show the virtues that cause one to go to heaven and the faults that keep one from going to heaven’.

The problem, as the Mahabharata presents it, lies not in dying but in dying for the wrong reason or in the wrong way. Since this is a heroic epic, a martial epic, it generally views dying in battle as a Good Thing. But to die in battle ignominiously, to die in the act of killing people one should not kill, or killing them in the wrong way, is not a Good Thing. Many of the battle deaths are unheroic, and they trouble the killers in the aftermath of the war. So, too, the death of Abhimanyu, just a young boy, all alone at the hands of a group of seasoned soldiers when his older companions failed to keep their promise to protect him, is a constant thorn in their side. The heroes’ surviving parents share these sorrows and have others of their own. King Dhritarashtra is haunted by the guilt of having failed to prevent his wicked son, Duryodhana, from waging the fratricidal war against Pandu’s five sons in the first place, and of having continued to refuse to stop Duryodhana (though many people urged him to do so) at various moments when it might have been possible.

The women who mourn their sons and husbands are generally not so troubled by these strategic questions of Geneva Conventions/Marquess of Queensberry violations; they simply grieve. But the two great mothers, Dhritarashtra’s wife Gandhari and Pandu’s widow Kunti, grieve in special ways that have consequences for the deaths and afterlives of the male heroes. Gandhari curses the men who had killed her sons and survived the war; as we have seen, she curses them to die in a strangely convoluted way many years after the war. Kunti’s grief is quite different: many years after the war, she regrets the loss of her child years before the war, when, in violation of dharma, she gave birth to a son—the tragic hero, Karna—whom she abandoned, also in violation of dharma. This abandonment of her son was the woman’s equivalent of a man’s sin in killing another man in battle in violation of the rules of dharma (which also happens to Karna, whom Arjuna murders in violation of the ethics of battle). Kunti’s painful recollection of her treatment of Karna torments her repeatedly in the aftermath of the war, until finally the sage Vyasa grants her absolution: he reassures her that she was guiltless in yielding to the Sun god and abandoning Karna. He justifies his argument by assuring Kunti that she had no choice but to submit to the assault, because the gods are totally amoral: ‘The dharma of humans has no connection with the dharma of the gods. You should understand this, Kunti, and let the fever in your mind vanish. Everything is within bounds for those who have brute power; everything is pure for those who have power. Everything is dharma for those who have power; everything of those who have power is their own.’ This is a stunningly cynical attitude both to the gods and to what humans are taught to believe is the basis of their own moral action.

When Dhritarashtra and the two queens finally die, there is yet another sort of dilemma about a good death versus a bad death, this time hinging on the nature of the forest fire in which they die. It appears to be a random fire of no religious significance, hence the agent of an ignominious, meaningless death, the equivalent, for a Homeric warrior, of being left unburied as carrion for the birds and dogs to eat. But the sage Narada goes to great, if ultimately unconvincing, lengths to persuade the descendants of the dead king and queens that the fire was actually a consecrated, sacred, ritual fire, which would mean that they did not die profanely; and eventually their bones are recovered and they are given a proper funeral. The idea that the source of the forest fire was a sacrificial fire is an example of another important and recurrent Mahabharata metaphor: the war as a broken sacrifice or uncompleted sacrifice, a sacrifice that goes horribly wrong.

Arjuna Visits Vyasa and Yudhishthira

Arjuna entered the ashram of Vyasa, Satyavati’s son, and saw the sage seated in a lonely spot. He went up to this man who spoke truth and knew dharma and had taken a great vow, stood beside him, and addressed him, announcing his name: ‘I am Arjuna.’ ‘Welcome to you,’ and, ‘Sit down,’ said Satyavati’s son, the great sage. When Vyasa, whose soul was at peace, saw that the mind of Kunti’s son Arjuna was unsatisfied and discouraged, and that he was sighing again and again, he said: ‘Have you been sprinkled by water from nails, hair, the end of a garment, or a pot? Have you attacked someone whose father was unmanly? Have you killed a Brahmin? Or have you been conquered in battle? Because you seem to have lost your lustre. I can hardly recognize you. What is this? If it is something I should hear, son of Kunti, you should tell me right away.’ Then Kunti’s son, sighing, said, ‘Listen, my lord,’ and told Vyasa accurately all about his own defeat.

Arjuna said: ‘The glorious Krishna, whose body was dark as a cloud, with eyes like giant lotuses, has left his body and gone to heaven with Balarama. When I remember that, I become constantly confused and grieved, and a desire to die constantly arises in me. Remembering the ambrosial happiness of looking at, touching, and talking intimately with that great-hearted god of gods, I grow faint. The hair-raising massacre of the Vrishnis in the Battle of the Clubs at Prabhasa, caused by the Brahmins’ curse, brought about the end of the heroes. Those great-hearted heroes with their great strength, proud as lions, the Bhojas and Vrishnis and Andhakas—they killed one another in a fight, good Brahmin. They who had arms like iron bars, and could endure maces, iron bars, and spears, were slain by blades of eraka grass. See the twisting of Time! Five hundred thousand of those men famous for their strong arms were slaughtered when they attacked one another. As I keep thinking about the destruction of those Yadus of immeasurable vigour, and of the glorious Krishna, I cannot bear it. Like the ocean drying up, a mountain moving, the sky falling, or fire chilling, I think the destruction of Krishna with his bow made of horn is impossible to believe. And without Krishna, I do not wish to remain here in the world.

‘And listen, you who are a Brahmin so rich in tapas, to something else even worse than this, something that shatters my heart as I think of it again and again. Right before my eyes, the Abhiras who live in the Land of Five Rivers pursued the wives of the Vrishnis in battle and abducted them by the thousands. When I took up my bow there, I was not able to stretch it fully, and the manly power of my two arms was not what it had been before. My various weapons were lost, great sage, and my arrows were exhausted in a single moment, all around me. That bow, and those weapons, and the chariot, and the prize-winning horses, all of it was shattered in a single stroke, like a gift given to someone other than a Brahmin versed in the Veda.

‘And the four-armed man with eyes wide as lotuses, whose soul cannot be measured, who carries the conch and discus and mace, the dark one who wears a golden garment, who goes with great splendour in front on my chariot, burning the armies of the enemies—I do not see him today. The one who burnt the enemy armies with his blazing brilliance as he went in front, while behind him I would destroy them with arrows released from my Gandiva bow—when I do not see him, my spirits sink, and I seem to whirl around; my wits become faint, best of men, and I find no peace. I cannot bear to live without the heroic Krishna, Exciter of Men; for as soon as I heard that Vishnu was gone, I was so bewildered I couldn’t tell east from west, north from south. Please, best of men, teach me what is best for me to do, for I have lost my relatives and my heroic power, and I am running about, empty.’