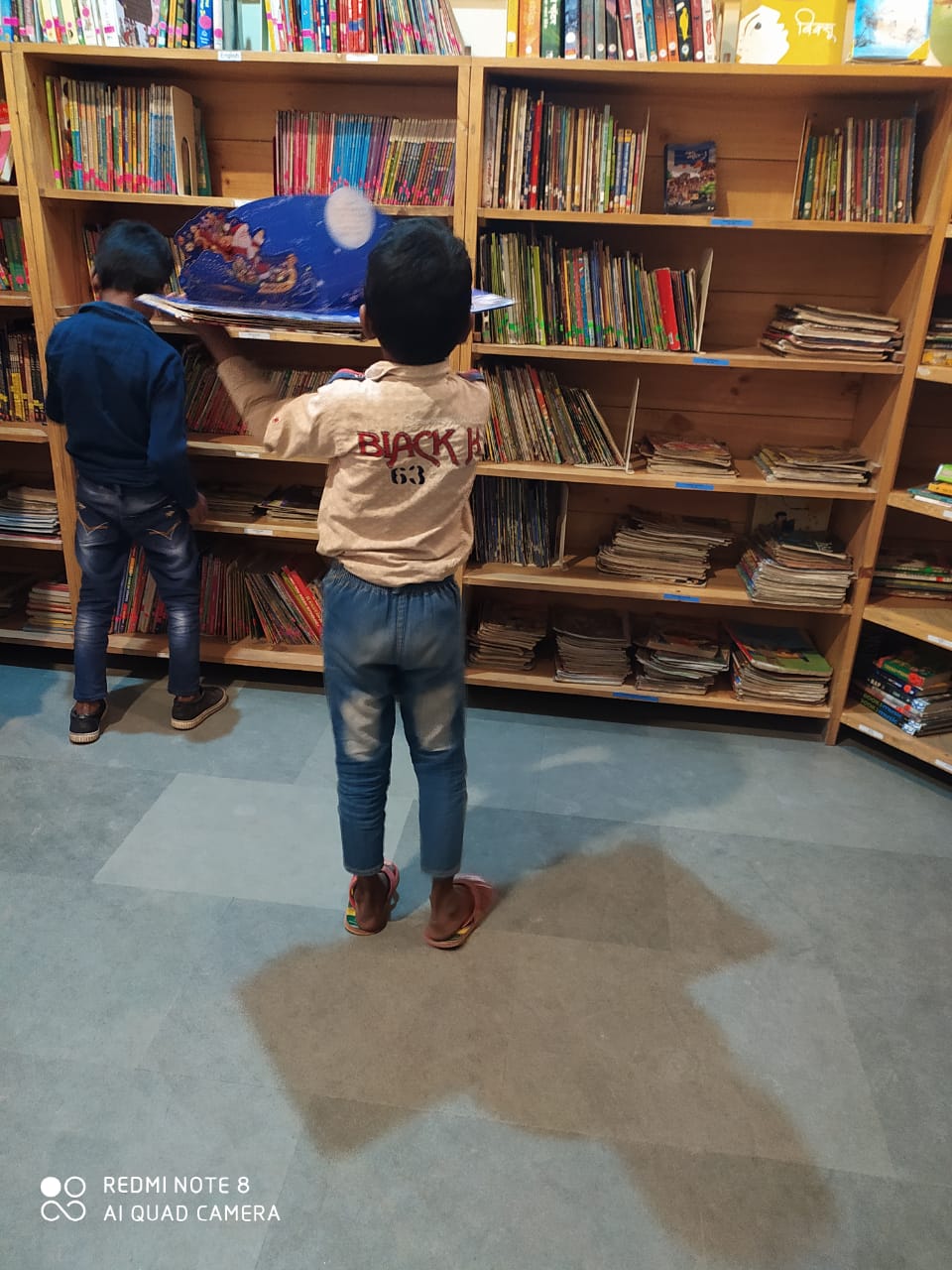

Started in 2015 from a small space of 500 sqft, The Community Library Project (TCLP), today has over 7000 members, a collection of almost 35000 titles and numerous other programs for children and adults. In 2020, soon after TCLP issued their 167,083rd book, the entire nation was locked down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and TCLP’s digital branch, Duniya Sabki, was launched. This year in September, TCLP issued their 200,000th book.

A community library, as Mridula Koshy says, “is a space in which everyone in the community is welcome, a space that meets community needs and builds the community through reading together.” Similar efforts are being made around the country, but these other libraries have mostly remained isolated from one another and outside the public eye.

Over 100 libraries came together between 2019-2020 to form the Free Libraries Network to change this. The network has been organising itself by mapping and documenting the existence of member libraries, defining standards and best practices, advocating and advancing the argument for libraries, and finally building support structures that allow libraries to flourish and the movement to grow.

The ICF team spoke to Mridula Koshy, writer and Managing Trustee of The Community Library Project, Purnima Rao, head of the Free Libraries Network and Zoya Chadha, the Project Coordinator for Duniya Sabki about The Community Library Project; its digital branch, Duniya Sabki; the Free Libraries Network and more. Excerpts:

ICF Team (ICF): Could you tell us more about how The Community Library Project (TCLP) began?

Mridula Koshy (MK): The Community Library Project was always set up to serve its members and function as a community library, while also being a learning lab where we figure out how to be a community library. There is no blueprint for creating libraries in India, i.e. libraries that serve first-generation schoolgoers and all those who have been excluded from literature through caste, class, gender and other means of exclusion. With no existing models, there was very little to go on when we began. Now we have a blueprint of sorts which exists in conversation with such documents as the IFLA UNESCO Manifesto.

So, it was important for us to work as a learning lab so we could not only run excellent libraries but also develop best practices and standards and model those to the world at large. And ultimately we mean to provoke some thinking around why, if a small community can create a library that works, are we not creating libraries everywhere so everyone has access to books, reading, information and the power that comes from such access. We are an advocacy organisation in that sense.

It was important for us to work as a learning lab so we could not only run excellent libraries but also develop best practices and standards and model those to the world at large.

We advocate and agitate, act as provocateurs around the question of the missing libraries in India, because despite understanding the importance of libraries for people’s access to knowledge we are a society that simply hasn’t invested in or taken responsibility for creating libraries. For example, Delhi has three dozen public libraries and even those are restrictive, in how a person might get a membership. Furthermore, a handful of libraries cannot serve the needs of approximately 21 million people.

In the process of doing this over the last few years, we’ve also met other people who are engaged in this conversation, who are variously trying all sorts of library ideas. And we’ve all been learning from one another. It’s become pretty clear to us that no matter how excellent TCLP is, or how excellent the Rohit Vemula library is, or the School for Democracy is, these various efforts around the country are largely going unrecognised. The hope for a free library movement depends on bringing these organisations together and first of all allowing us to recognise ourselves and then to demand recognition from others, If we don’t work with others, it is possible for TCLP, situated as it is in Delhi, to become a pet or a darling of the literary community — writers and publishers who do support us without ever having that translate into the justice work we’re trying to do.

Our curriculum team, for example, has, over the years designed the kinds of interventions that should be adopted across the country and be a part of the National Education Policy. We’ve developed an understanding of what children need, and what it would take for first-generation schoolgoers to read. But how can a small project with good engagement and great success, translate into something that our society is ready to grapple with? To answer that question, I think we need to look at what the Free Libraries Network is doing.

ICF: The Free Libraries Network (FLN) is a network of community libraries across South Asia. Can you tell us what other organisations/libraries are involved in the network and how it evolved? What does the network aim to achieve?

Purnima Rao (PR): For years before FLN was formed, TCLP was being contacted by and getting into some very informal conversations with practitioners who were, in their way, running free library projects across the country. TCLP was being approached for two major kinds of assistance. One was for help with curating library collections and procuring books. Practitioners didn’t know how to access publisher catalogues and donors or how to build a strong collection on a shoestring budget. Secondly, practitioners wanted to get into a conversation about librarianship itself. We just don’t have conversations about librarianship in this country, and we don’t know where to go seeking them either.

So the next organic step was to make a network. In 2019, a few of us made a Facebook group and started conversations about librarianship. I think even those early conversations showed how everyone, regardless of socioeconomic background or the extent of exclusion, understood the importance of books in a non-academic sense. Everyone understood how critical the need was, and how little this need had been served. But then what do you do with that? You can put books in a room, but then what? This was the missing chunk of information.

We saw these libraries become a place where we could connect communities with critically important information resources.

While we were trying to understand and work through this, the pandemic hit. Most practitioners in FLN are catering to people from marginalised backgrounds, low-income communities, remote communities and rural communities who may or may not have access to good schooling. What we saw during the pandemic was that the libraries were used not just because there were books and reading programs for children who had lost touch with the school, which is invaluable, but also as an information hub to find out what is happening in the city or their region. In some villages, it became a hub for ration and medicine distribution.

We saw these libraries become a place where we could connect communities with critically important information resources. The librarians also realised that their space is something bigger than one practitioner wanting to fill a room full of books and saying, “Okay, we’ll bring books to this community.” That’s when the network grew not just in consciousness but also numbers.

Today, FLN has over a hundred members from all over India, who are creating free libraries that cater to the needs of its community. So while each library will be different from the other, we are all talking about a certain universality of running libraries. We believe that libraries by definition must be free, so anyone who is running a free library can join us.

We run a couple of programs, which are designed for resource-sharing including a book dissemination and curation program, where we invite book donations from individuals or publishers who understand the importance of free libraries but can’t reach the free libraries that FLN can. We also do a series of training sessions and advocacy webinars with publishers, think tanks, government agencies — for building consciousness about what it means to be in the free library movement, as we call it.

ICF: With the Free Libraries Network, what kind of support have you received from writers and publishing houses?

PR: When the network was not as strong as it is today, which is not a very long time ago, we were desperate to get into conversations with publishers, writers and other members of the literary community, to conceptually understand publishing in the context of free libraries. There are so many intersections but somehow the system is set up in such a way that the library almost always depends on the largesse of the publishing world rather than it being a partnership of equals, committed to serving readers everywhere. But it’s a process and from that point to today, many publishers are beginning to understand that they are direct stakeholders.

ICF: Can you tell us about the shift to the digital library mode after the pandemic and how “Duniya Sabki” works in tandem with the physical community libraries?

Zoya Chadha (ZC): Many relationships had been built in TCLP’s physical libraries — the membership that we already had, the members that had been coming and going across our physical library branches and had built relationships with the library, with books, with reading, with thinking through books. Duniya Sabki, our digital branch was built to continue that relationship and to also look at our members’ needs during the pandemic.

We looked at several questions before starting Duniya Sabki. How can we ensure access to books and to thinking books through a digital branch? How can we make it as relevant and accessible as possible for our members? How does the role of the librarian change during this time?

We understood that members do not have unlimited time or unlimited data when it comes to smartphones so all our content was made keeping that in mind.

We knew that we had to continue the relationships we made with our members. We also knew that there was a wealth of digital material available on the internet. But just because something is online, it does not mean that it will by default reach more people across the world. So, we had to consider accessibility, data requirements, platforms on which our material could be made available, the devices needed to access it, and much more.

Our first step was to organise our membership into several channels. We used WhatsApp because it was the most commonly used among families with access to smartphones. So, we organised our membership into 12 WhatsApp groups and began sharing videos and audio of stories. We understood that members do not have unlimited time or unlimited data when it comes to smartphones so all our content was made keeping that in mind. We were sharing very short audios and videos by librarians — who the members were already familiar with, who they’d been seeing in the library branches — reading aloud stories, inviting members to think and so on. We also shared reliable information about COVID, the different government schemes and more that could be useful to our members.

One of the things that we were very firm about, and still are, is that our digital branch is not in any way a replacement for our physical branches. It was urgent at the time for staying connected with our members, for continuing their relationship with books and reading and also for sharing relevant information that was not readily available otherwise. And it has proved to be a very interesting platform to bring member voices and community voices together in this digital media space since then as well.

Running Duniya Sabki has come with an understanding of our immutable responsibilities as librarians. We as librarians are learning a host of new skills to be able to serve our members digitally.

PR: We also understood that not everyone has access to even be able to join the WhatsApp groups. So we ran awareness campaigns during the lockdowns. We wanted the people and the government to understand that online education cannot be a success unless everyone has free internet access. At TCLP, advocating for free internet for all is an important aspect of the work we do.

ZC: Just putting things online and continuing to invest in these online platforms without addressing what Purnima talked about — the unavailability of devices and free data — is just increasing inequity in our country. We can build all the platforms and education resources we want, but it is the government’s responsibility to look at and bridge the increasing divide between those who have access to these and those who don’t.

ICF: As a ‘learning lab’, TCLP and FLN constantly try to understand and cater to the needs of the readers. What are some of the mechanisms that can help bridge the gap between the publishing world and the readers?

PR: I think it’s really important to acknowledge that, while there have been literary discourses on books — the writers, publishers, editors — there just isn’t enough curiosity about where India’s readers live. As a result, within the literary community, very little is known about India’s readers — who they are, what they need, how they read, what they enjoy, and how pleasure is derived from books. Many people, who claim to represent the Indian literary space, have shown little curiosity about who reads their books or where they’re reaching.

And this is where the library movement plays an important role because all libraries do, is interact with readers day in and day out and create ways in which we can serve and reach more and more readers.

Within the literary community, very little is known about India’s readers — who they are, what they need, how they read, what they enjoy, and how pleasure is derived from books.

There has to be a deeper investigation into why there is a crisis within the publishing world and what aspect of it is connected to a lack of understanding of where India’s readers are. Libraries are spaces where this work is already happening, these are spaces owned by and catering to all kinds of communities. It’s high time the connections between the publishing world and the library world are seen, understood and discussed.

MK: The FLN compact is one way of doing this in an organised way. It’s a formalisation of an agreement we want to see. That agreement doesn’t exist right now but it is calling upon all of us to recognise the existence of the readers who do not enter shops to buy books, who do not find books in their school libraries because it’s not set up that way.

By signing the compact, you’re stepping into that recognition, you are planning to start thinking about this group of people. You are acknowledging that literature exists for readership, and therefore, the editors, writers, illustrators, and publishers, who are creating this literature have something in common with the readership that’s coming into this literature. You are also acknowledging that a lot of readerships are not coming in and we need to find ways to change that. This compact is a mechanism for making that happen.

There will have to be many more such mechanisms. For example, outside of the compact, we’re having individual conversations with several publishers. But there’s a long way to go and all of us who have access to and who are creating literature need to get busy with this very quickly.

ICF: Could you talk about libraries as means of protest and resistance?

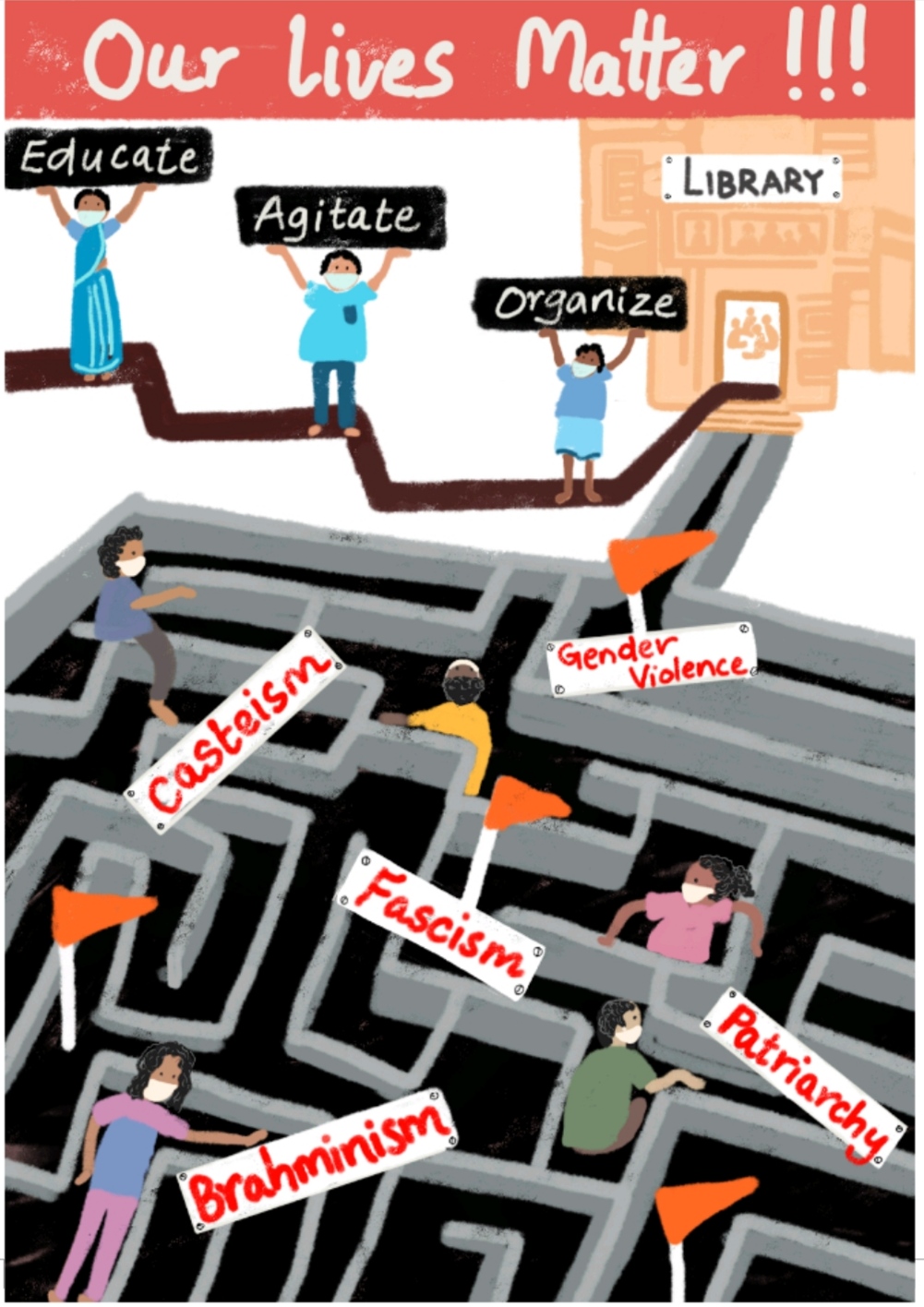

MK: Literature is a force for change, for justice, and limiting access to literature is a great way to exert control over a society. Ambedkar’s call to educate, agitate, and organise is central to our work. Free libraries are places that educate all people. The active exclusion of people from literature through confining books to bookstores and through the failure to create a public library system is ripe ground for a movement that is agitational and that ultimately will have to organise itself. Free libraries are a means of justice, one can even say without libraries there is no justice. And this knowledge exists within the state as well, which is why we see a repressive state come after libraries.

So yes, this is a long-understood relationship – between books, free libraries and justice – but one that in India requires us to organise if we wish to see the relationship realised. We have to keep alive the understanding amongst ourselves that we read and write to do the work of justice. Literature exists to empower us to do the work of justice.