At least thrice a year, Warli artist Meena Parhad prepares her artworks for the Dahanu district exhibition. Organised close to the community’s homeland, the exhibition showcases many women Warli artists who otherwise struggle to present their works to the world. For Parhad, these local exhibitions are especially important because they portray original Warli paintings that convey a story for those able to read the “lipi” (language).

Warli is an art form created by the tribal women of Warli and Malkhar koli tribes, residing on the northern outskirts of Mumbai, Maharashtra. According to the local collective Adivasi Yuva Shakti (AYUSH), Warli was the only means of transmitting folklore within a community unacquainted with the written word – thus inspiring the notion of ‘a lipi’.

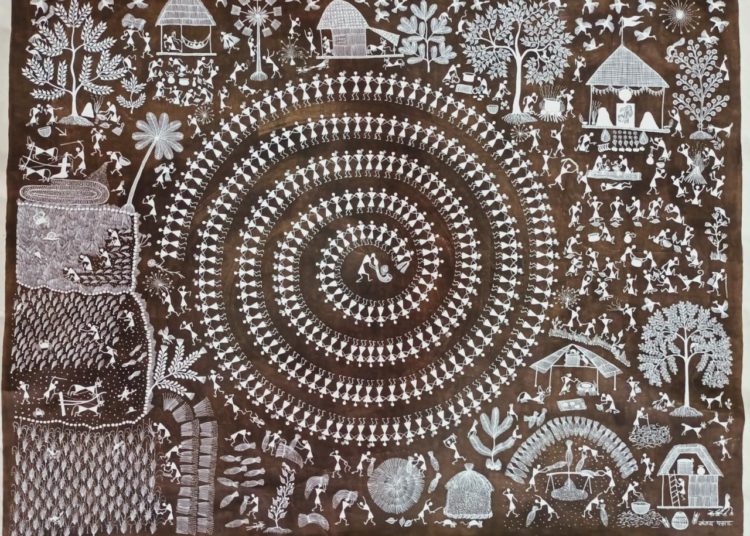

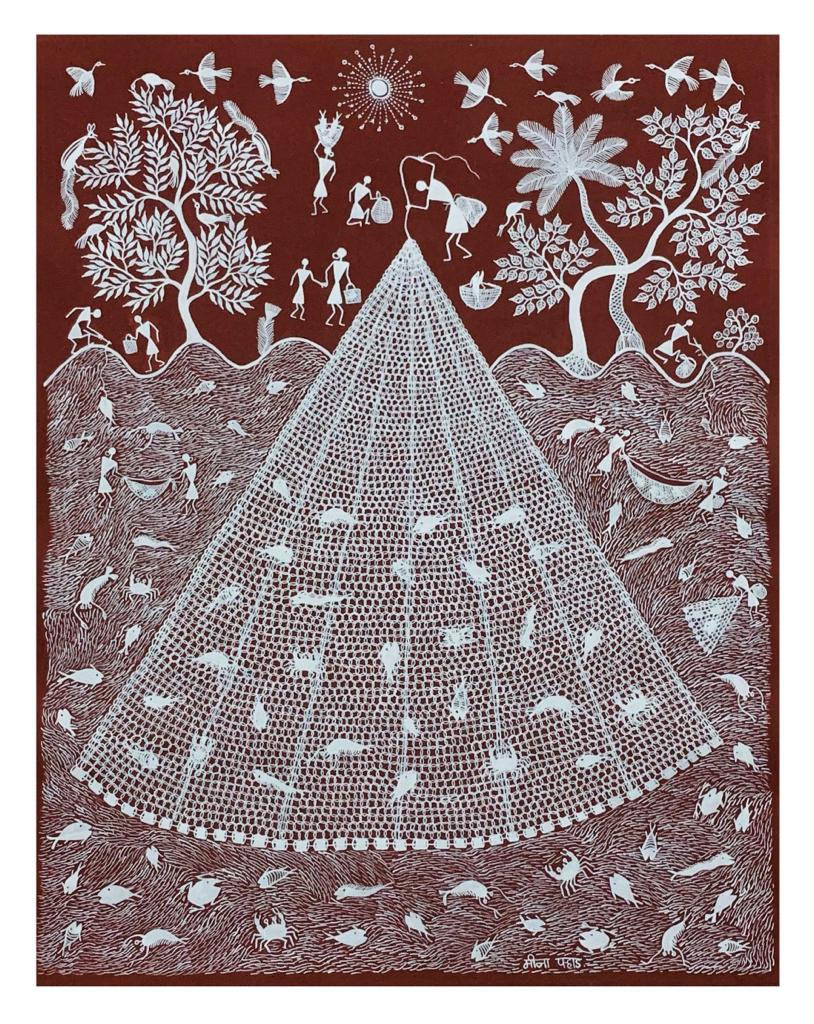

The paintings use rudimentary geometric shapes such as circles, triangles and squares to talk about community life. The circle represents the sun and moon while the triangle was derived from mountains and pointed trees. While the square shape represents human invention like a sacred enclosure or a piece of land.

Another important feature of traditional Warli art is that the paintings were made by women during auspicious events or during celebrations. Rather than mythological characters, these paintings depict social life. Parhad recollects how she learnt the art from her mother and grandmother who sat together and painted a “lagnachi chauk”. Men began practicing Warli art once it became a source of livelihood. However, the lagnachi chauk is still created by women while the men depict daily life.

“We also paint Warli art on house walls when a child is born in a house or when the first harvest arrives, basically any big celebration,” Parhad said to Sabrang India.

Having learnt to paint since 2012, Parhad knows how human beings and animals are to be painted in a rhythmic pattern rather than in monotonous straight lines. In ritual paintings, the square is the central motif as the chauk inside which we find the tribal mother Goddess Palaghata symbolising fertility.

Fellow Warli artist and Parhad’s husband Sanjay Parhad says these rules are important because they distinguish Adivasi art from non-Adivasi art. Speaking to Sabrang India, he says the absence of a tarpa (musical instrument) in a tarpa dance painting is the same as forgetting the Ashoka chakra in the tricolour flag.

“It is insulting to the painting too. Warli is not drawn but written. It is our language. The chauk is not a design but each aspect has a message. That chowk is worshipped,” says Parhad.

Similarly, Meena Parhad talks about how she often has to explain and narrate the story in her art when at the exhibition. However, non-adivasi artists do not bother with such details.

“Adivasi Warlis have an understanding of the art. Meanwhile, non-adivasis create anything, put any feature anywhere. There is no meaning to it. I feel if they are making the art, they should at least have a story behind it,” she says.

It is for such reasons that the community, disappointed by the lack of recognition for indigenous artists, resolved to claim a Geographical Indication (GI) tag.

Warli adivasis’ struggle for GI tag

A GI tag is a name or sign used on products which corresponds to a specific geographical location or origin under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999. It was enacted by India as a member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

The story of Warli’s tag starts with the AYUSH group. According to founder Sachin Satvi, the group originally only wanted to create awareness about Warli art via a blog. Earlier, the collective had provided career guidance and information to community youths. Later, members decided to help the Adivasis who couldn’t complete their education.

They resolved to experiment with traditional knowledge like art and medicinal tactics. Since Warli art was already popular with the NGO’s establishment in 2011, members resolved to promote it as a form of employment.

“We found a neighbor’s painting online and copy-pasted it with credit [to the artist]. A day or two later we received a letter from French and German galleries asking us to remove the image or they will take legal action. We were shocked,” says Satvi.

Although AYUSH removed the image, members were unsettled that their cultural heritage was owned by other countries under copyright. Satvi says that it was then that AYUSH decided to apply for a GI tag.

However, doing so was an uphill task. Although AYUSH applied to government ministries everywhere, they received no support. The little help they got was by way of maps marking tribal areas although these were already in public domain. The organisation considered getting a consultant but then decided against it.

“We had no money for that. Also, we wanted to understand this process because there are many other art and craft skills that we want to promote. We want to design programmes that create an ecosystem for skill development and alternate livelihood so there’s no need to move out,” says Satvi.

Why do tribals want community recognition?

The threat of ‘moving out’ from their homeland is ever-present for India’s tribals. Adivasi history is filled with struggles to protect their traditional land. For them, a change in place of residence affects their livelihood and cultural identity.

Satvi says this is especially true for Warli art. The paintings often depict how natural resources impact Adivasi life. As such, the image is affected once the environment changes.

“When the homeland is taken away, lifestyle changes. Warli art has geographic relevance. If no mountains or rivers are left to show, will Warli art stay the same?” asks Satvi.

Satvi says that one of the reasons the community promotes Warli art is to help non-Adivasis understand tribal outlook of the world. He points out that while the media and government officials talk about ecological impact alone, there are other ‘impacts’ that cannot be quantified.

For example, the younger generation of adivasis struggle to get jobs after their graduation despite reservation. They are forced to take the money offered for their land. However, even this money is lost since tribals do not have access to financial planning. Moreover, many older generations are unwilling to leave their land.

“It worries me whether the GI tag will be of any use if our land is taken away for development project… I feel that the administrative and the general public needs to understand such things,” he says.

Currently, Palghar and Dahanu’s tribals face an uncertain future owing to the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train project that (once commenced) will pass through the indigenous community’s land. However, with regards to the project’s rehabilitation plan, Satvi says that the document is not explained in an accessible manner as mandated in various forest rights acts. Further, he says there is no provision of skill development for their future livelihood.

What next for the Warli folk?

By 2014, AYUSH got the GI certificate. However, it wasn’t until recently that the move proved to be profitable. Until 2020 or so, AYUSH received a lot of criticism for investing time and money in this project. This was because the GI’ effect depends on authorized user registration but the community received no support for this.

“But in recent 3-4 years there’s a change. Ministries dealing with commerce and corporate affairs are slowly taking GI-related exhibitions,” says Satvi.

Still, he emphasizes that there is much more that the government needs to do such as implement direct funding, raise awareness and redesig existing schemes. He recalled how Maharashtra’s Tribal Ministry gave the local artists a chance to portray their work in Kolhapur. However, the community did not have the monetary means to go to the city.

“Some schemes’ eligibility criteria are also irrelevant on-ground. So on paper, it seems like the scheme is not being used,” he says.

When asked what customers interested in Warli art can do to help with tribal empowerment, Satvi spoke about the need for a lucrative vending platform.

“Many artists make what comes to their mind. But if you can tell them about demand, financial transactions, where raw material is available cheaply, that will help. Also, give presence to Warli art. Even that will have a huge market. The layers between the artist and market will be reduced and artists will talk directly to customers,” he says.

He also stresses the importance of fiscal support for an inventory. This helps customer-vendor communication as people will be able to see the product first. Currently, AYUSH is working with a cluster of 500 artists and has organised activities in Palghar, Dahanu and Talasari. The products of these artisans are available on AYUSH’s website.

All Images Courtesy Sanjay & Meena Parhad.