Twenty-two-year-old Wendy Doniger of Great Neck, Long Island, NY arrived in Calcutta in August 1963, on a scholarship to study Sanskrit and Bengali. It was her first visit to the country whose history and culture she was deeply interested in. Over the coming year—a lot of it spent in Tagore’s Shantiniketan—she would fall completely in love with the place she had till then known only through books.

The India she describes in her letters back home to her parents is young, like her, still finding its feet, and learning to come to terms with the violence of Partition. But it is also a mature civilisation, which allows Vishnu to be depicted on the walls in a temple to Shiva; a culture of contradictions, where extreme eroticism is tied to extreme chastity; and a land of charming absurdities, where sociable station masters don’t let train schedules come in the way of hospitality. The country comes alive through her vivid prose, introspective yet playful, and her excitement is on full display whether she is writing of the paradoxes of Indian life, the picturesque countryside, the peculiarities of Indian languages, or simply the mechanics of a temple ritual that she doesn’t understand.

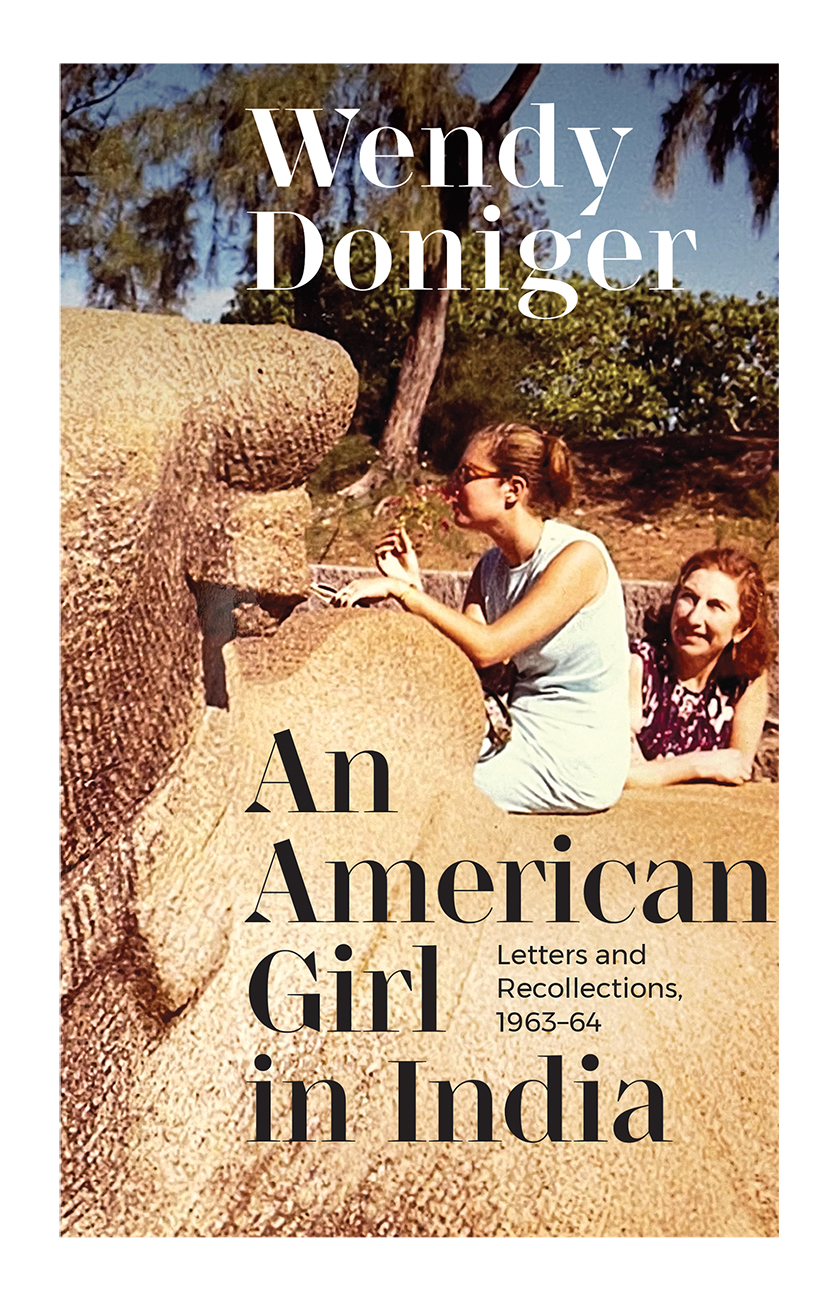

The following are excerpts from her book An American Girl in India: Letters and Recollections, 1963-64.

What emerges from these letters is the voice of the person I was then, an American girl who embraced Indian excess of all kinds, the bright colours of the women’s clothes, the subtle spices of the food (and how I loved eating with my fingers! I’d always hated knives and forks), who loved Indian art that packed so many things into paintings and sculptures that it made Rococo look like Bauhaus. And Indian music, where you slip up the scale instead of having separate notes—everything about India appealed to my personality. The word ‘wonderful’ recurs again and again and again in these letters (my computer counted forty-seven occurrences); I was truly full of wonder so often that I ran out of other words. Yet, throughout my stay in India, I ricocheted between my deep love of Indian culture and my childish recoiling from the poverty and the suffering. I was haunted by my inability to love everything about India.

What I see and hear in these writings by my young self is a stunning experience of kindness and generosity from a number of complete strangers, as well as lasting friendships with several extraordinary people. I think these magical cross-cultural encounters were made possible in part by my own youth and my great passion for the land of India and its culture, and in part by the youth of the country itself, so newly freed from the colonial yoke, not yet darkened by the rise of a jingoistic and repressive Hindu theocracy. Sadly, I cannot imagine such open-hearted and joyous encounters between an American visitor and the average citizen of the India of today. And yet the memory of those happy and innocent days in India long ago gives me courage to hope.

[…]

India seems to be the land of homesickness, and not just because I see it through homesick eyes. To stay alive, people have to move all the time, separate from their families, learn a new language. Almost everyone I know comes from somewhere else, and when people meet there is always a momentary shuffling of tongues until they decide in which of the many Indian languages of which each has a smattering they might best communicate: one knows Gujarati well and a little Hindi and less Bengali, the other knows Bengali well, a little Hindi and less Gujarati, so they settle on Hindi. Everyone is fiercely proud of his province, his language, his music, and adopts only with a great deal of criticism the culture of the province to which he has been forced to move. They are as proud of the group of huts which flood or famine or Partition caused them to leave behind as the Brits are of their lost ancestral castles.

Chanchal has taught me to play Ludo, her favourite game, which turns out to be none other than Parcheesi [the Indian game of Pachisi].

At night the insects swarm in thick masses around the lights, almost blotting out the light, and in the morning they are all dead on the ground, forming a bed that goes crunch when you walk over it before the sweepers come and clean it out.

Something that one cherishes as especially precious is known as ‘a widow’s son’.

Yesterday they came and cut away the little tree that grows outside my window, trimming it down to the stem. It grows so fast that in a week it will be back up to the roof, but for now the light comes straight in, and my little friend the yellow bird is finding his solace elsewhere. The clipping of the trees has filled the air with a fine, sweet, minty smell. They are also going to burn down the fields, so that the snakes won’t breed in them.

Now that I am on better terms with Bengali, I realize that the presence of English words is an insult to their language, not to mine. For Bengalis to have to sound out ‘tee-ya-tar’ (theatre) or ‘chay-ar’ (chair) or ‘glisherin shope’ (glycerine soap) is to have to admit that their own cultural version of these things was rejected by the dominant colonial culture in India, as was their word for them. There is a very bitter Tagore poem that expresses this, called ‘The Plump, Crying Tiger’. Here is my translation of it:

There was a plump, crying tiger, with spots, black, on his body.

Entering a house to eat a bearer, he saw himself in a mirror.

He went up to the bearer and asked him, ‘I want glisherin shope [sic].’

The boy said, ‘I’ve never heard of it in my life. I’m of low caste.

English, Shminglish [literally: Ingrij tingrij], I don’t know it.’

The tiger said, ‘You must be lying. I have two eyes to see with.

How could you have gotten the spots off your body without glisherin shope?’

The boy said, ‘I’m black as Krishna. I never rub anything on me like that.

You make me laugh. I’m no sahib [i.e. white man].’

The tiger said, ‘Shame on you. I’m going to eat you.’

The boy said, ‘Chi, chi, you would lose face by that.

Don’t you know, I’m an untouchable, a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi.

If you eat my flesh, you will lose caste.’

‘My, my, Ram, Ram,’ said the tiger,

‘It would be a scandal in the tigers’ quarters, and

My daughter’s marriage hopes would be destroyed.

The tiger goddess would be angry. Never mind the glisherin shope.’

The satire on English colonialism, while pretty much self-explanatory, might be clearer if I explain that the words ‘glycerine soap’ are sound-for-sound transliterated into Bengali, as so many names of non-Indian things are; also that the tiger came to eat the boy in the first place, though he makes it seem that he is just doing it as punishment for there being no glycerine soap; and ‘sahib’ is, here, a very bitter word for a white man, though, as a matter of fact, it is the only word used for a white man even when no bitterness is particularly meant.