In the India of today, social and communal fault lines have become starker than ever before. Inter-faith marriages, once seen as the hallmark of a plural society, are now being increasingly used to further a divisive political narrative.

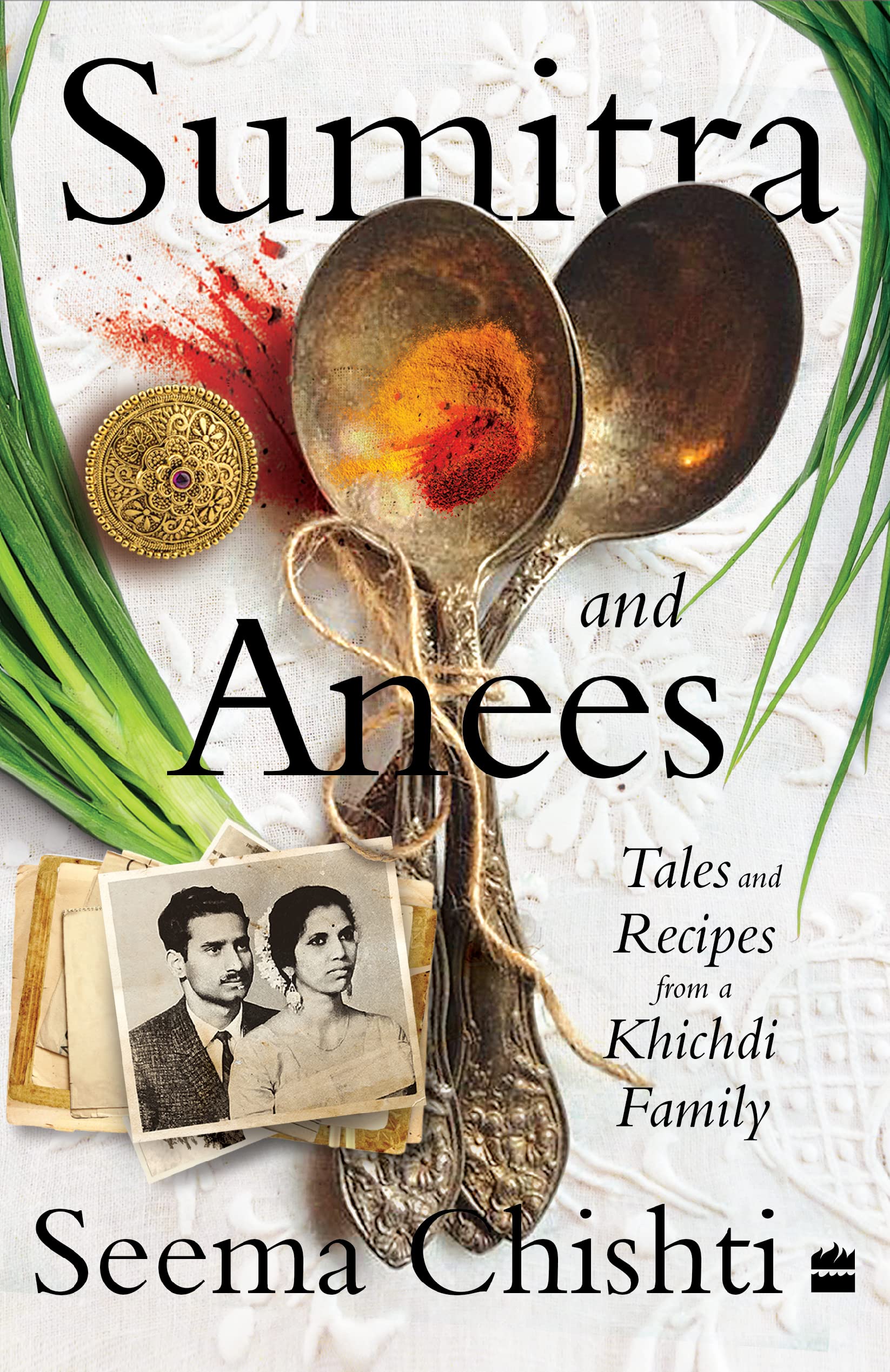

In Sumitra and Anees: Tales and Recipes from a Khichdi Family, journalist Seema Chishti, herself the product of an inter-faith marriage from a time when the “idea of India” was not just an idea but a lived reality, tells the story of her parents: Sumitra, a Kshatriya Hindu from Mysore in Karnataka, and Anees, a Syed Muslim from Deoria in Uttar Pradesh. Woven into their story are recipes from Sumitra’s kitchen, a site of confluence for the diverse culinary traditions she mastered.

In this conversation with Githa Hariharan, Chishti talks about the book and more.

Githa Hariharan (GH): I want to begin with your book’s subtitle, Tales and Recipes from a Khichdi Family. The phrase holds some of the critical aspects of human experience, from story and food to family and the heart of the home, the kitchen. How did this title come about?

Seema Chishti (SC): Khichdi, a mix of rice and pulses (and more) is considered a mish-mash and has always fascinated me. I always felt I was part pulse and part rice, so to speak. Then, like all good and useful things, it is also undervalued while speaking of high cuisine. We know how invaluable khichdi is when you have a patient at home. I wanted to own the word in how I saw my home – proudly – as not monochrome; as a khichdi thing. Society does not seem to be in very good health at this time, so I thought I must draw in the khichdi reference. Then there is also my mother’s recipe book that she left behind – so it all worked well, to riff on the food aspect of my book and the idea of a healthy, “mixed-up” food item. What better way to encapsulate Sumitra and Anees coming together, than with a reference to khichdi?

GH: The khichdi is a great metaphor for a diverse country and for the story of your parents’ lives together, a sort of lived unity in diversity. (It’s also useful to remember that khichdi has vegetarian as well as non-vegetarian versions.) How do you think your parents managed to throw out all purist notions to embrace this plural “khichdi” identity, as individuals, as a couple, and as a family? And how did you cope with this sensibility as you were growing up?

SC: My parents got together in a world that was not so openly hostile then. This is not to say that prejudice, or a sense of group identity, did not exist then. After all, it is not an invention of the present. But it has now been sharpened and weaponised. It is articulated in ways that appear much more brazen, partly due to the times, due to new technology and more. In hindsight, I think it would be fair to say that the two of them benefitted greatly from each other’s influence and from living a life together. It enabled them to not just be who they were, as individuals, but also something else. They created something as Sumitra and Anees together – more than a sum of their parts, as a unit. So we were culturally happy to be Hindu, Muslim and more, possibly Christian and Sikh too, but we were also happy to not fit into one single box. By virtue of the fact of their personalities and the bond that held them together, my parents were both mature and deeply connected to their cultural roots. This made them more accepting of others. In fact, it made them anxious and eager to constantly learn more and more. Importantly, the Indian State was a different creature then – we are talking of the early years after Nehru’s death – so the modernity his stint as PM had infused into how the Indian State behaved or what it stood for, was still alive. The fact that the State was not an active enabler of societal prejudice and biases made it possible for Sumitra and Anees to not be solely preoccupied with security issues as couples belonging to different religions would be today. So they could think more about thriving, than just about surviving.

GH: The silly stereotype of a cosmopolitan is someone privileged, flying from place to place. But your book indicates some of the deeper meanings of cosmopolitanism, even in a small town in UP. Who is a cosmopolitan for you? And why are true cosmopolitans an endangered species?

SC: Ah. A very good and important question. It is fashionable to hold out a candle to regressive “nationalisms” in Europe and elsewhere, citing “cosmopolitan elites”, as the reason for the so-called “rage” of those voting for far-right parties. That, according to me is very clever and deceitful propaganda. It makes crossing narrow identity issues a class issue too, by misrepresenting cosmopolitanism as something elite and alien – and of jet-setters as you say. This take-down of cosmopolitans is at the heart of a sophisticated sons-of-the-soil argument, which is actually a plea for the narrowing of the mind.

The ‘one-leader’, ‘one-tax’, ‘one religion’, ‘one-man’, ‘one kind of food’ line pushed ad nauseum is to close minds down and crack down on critical thinking and reasoning.

For me, a cosmopolitan mind is an open one, which is not limited by boundaries imposed by h/er own ascribed identity and in all manner of speaking is evolved, engaged and happy to form partnerships and associations with others not of the same kith/kin/clan. To my mind, a cosmopolitan person is not a jet-setter or someone who has travelled the globe, but an evolved person, who is a sum of all the parts that constitute life on the planet – so is happy to accept “other” languages, ways of being, thinking, living, eating, loving, which were not known to h/er, or prescribed at birth. Evolution and engagement with the whole wide world, in a way that is non-hostile, capacious thinking – where the cosmos is the unit of operation – maybe that is the origin of the word?

They are seen as an endangered species as politics is, currently, in several parts of the world and especially in India, held on a tight leash by people who do not want their electorate to think deeply and for themselves. That would open up minds and options. The “one-leader”, “one-tax”, “one religion”, “one-man”, “one kind of food” line pushed ad nauseum is to close minds down and crack down on critical thinking and reasoning. So cosmopolitanism is under attack and mocked at as alienated and elite and disconnected. It is important to mock and discredit – call the dog mad before you shoot it. If a significant section of the electorate thought like cosmopolitan people, that would be the end of the narrow kind of India they are trying hard to create.

GH: Would you comment on the importance of mixed marriages, whether in terms of community, caste or region? Not only to make laws such as the Special Marriages Act work, but also to resist new laws that criminalise interfaith marriages, or increase the number of impediments to mixed marriages? How do they bring communalism / casteism and patriarchy together?

SC: It is interesting (and sad) that inter-religious marriages, based on NFHS data, remain about 2.5% and less, inter-caste too is at around 13%. (I suspect these inter-caste marriages may not necessarily be a radical choice. They could be marriage among the savarnas or within categories of dalits – not across the big dividing lines.) The young in India today are no 1968 generation. Available data (World Values Survey and Pew Reports) suggests that they are quite conformist and behave as their “elders” would.

Yet even this small number of “mixed” marriages matter. How the state and society respond to such marriages is a useful barometer to judge how open-minded its people are, and how accepting of pluralism society is. It is not as if everyone must cross-marry to prove a point, but how you look at people who have, and how the state reacts. Together, this makes for a very important indicator of how democratic the place is, and how enlightened and accepting its people are of new ideas.

Also read | Sumitra and Anees: Tales and Recipes from a Khichdi Family

The laws currently targeting mixed marriages are serious prohibitors and give a clear signal about where the state stands with reference to pluralism, modernity and patriarchy. In one fell swoop, by cracking down on “our women” marrying outside the community or region, you establish control over women, reduce them to possessions, and ensure that the patriarchy continues to reign. Inter-community ties remain fraught and social mobility is also killed. These laws, like the Nuremberg laws, are not only about showing a community as inferior or different. But as family structures in feudal set-ups like ours are central to maintaining all manner of retrogressive attitudes, to keep an endogamous and conservative family going is an imperative if you want to maintain patriarchy as well as communal and caste divides. So it becomes a political project too to control the family, as that keeps society regressive.

The laws currently targeting mixed marriages are serious prohibitors and give a clear signal about where the state stands with reference to pluralism, modernity and patriarchy.

I cannot see any way of enabling laws like the Special Marriages Act of 1954 to be made to work for the purpose it was intended to work for, without a change in politics and without fostering a larger mindset which accepts that India must modernise. Currently, the spiel being fed is nostalgia, for a return to a mythic and contrived ancient Hindu past, which means “stability” and a social order which is unequal, separate, and certainly not giving women and dalits agency.

There is a telling comment in S Rukmini’s book, Whole Numbers and Half Truths: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us about Modern India, when she is talking of the miniscule numbers of mixed marriages. One interviewee tells her that she is looking at the wrong variable –marriage. He suggests she look at how many of those in love are choosing partners across religion and caste divides. But that sounds like Madhubala in Mughal-e-Azam. Pyaar kiya to darna kya? – and if that was to be written today, it may well face the censor’s axe – it is far too liberating.

GH: You have a lovely description of your parents’ life together: “the big promise of India they brought into their modest home”. Would you say they were actually “living” the Constitution as good citizens should, making those words and aspirations real? How different was their effort to bring India home and yours?

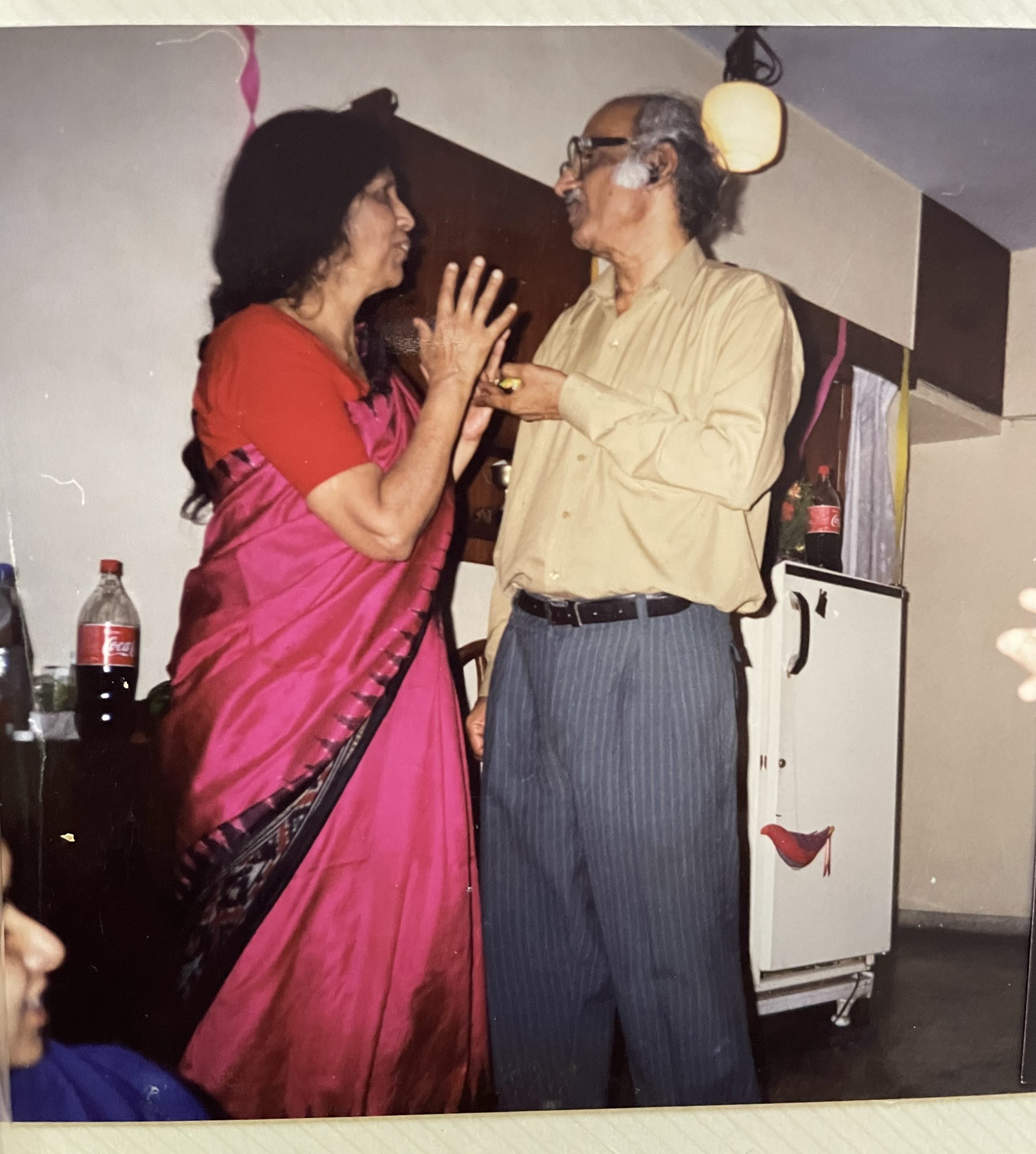

SC: Their meeting in Delhi, hailing respectively from Mysore and Deoria, was a coincidence. But on becoming partners and building a home together, they went on to become more than what they would probably have been, had they not come together as a couple. They enabled their only child (i.e. me) to acknowledge and accept all sides of her identity and take her time to accept it and be whoever she chose to be. That is a big tribute to the kind of home they built.

I don’t think they set out to do a “model citizen” number, but allowing the wind to blow into their home from all sides, sweep in with it whatever it did, and to be able to deal with—all this was extraordinary. No one really ever finds themselves, that quest is eternal – but I could be myself in their home/our home – and that meant different things at different stages in my life. The same experience was shared by my friends over the years and my family that I chose to build as an adult. I think that is a tribute to “the big promise of India they brought into their modest home”.

Friends of my parents, family and acquaintances, will bear witness to what their presence, and way of thinking meant to them and enabled in them. My parents ended up being a support system for so many people over the years, people who broke barriers of all kinds – whether it was the unconventional subjects they chose in college or their choice of life-partners. As I say in the book, at the risk of sounding corny, taboos were the only taboo.

In the lottery of birth – I was the apple that fell from the tree. By the fact of my DNA and upbringing – nature and nurture, both – I happened to witness and inherit values that I absorbed and lived by. When I look back, I can say with some confidence that I always made non-parochial choices. I was never guided by narrow concerns of ethnicity or identities ascribed to people at birth which they are forced to accept as immutable for the rest of their lives. So in that sense, I did and do make the promise of the Indian Constitution a lived reality in my little home too.