In the India of today, social and communal fault lines have become starker than ever before. Inter-faith marriages, once seen as the hallmark of a plural society, are now being increasingly used to further a divisive political narrative.

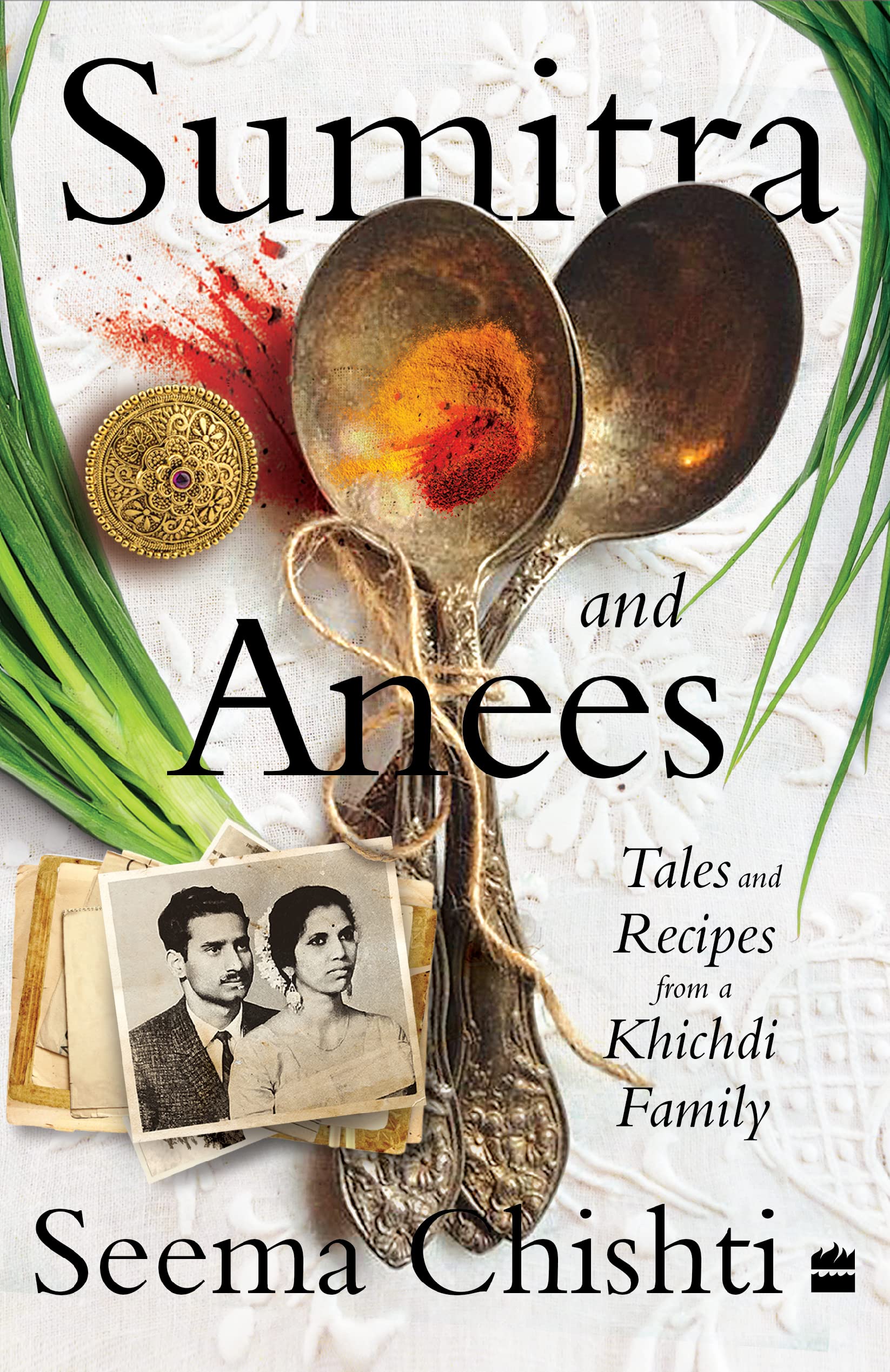

In Sumitra and Anees: Tales and Recipes from a Khichdi Family, journalist Seema Chishti, herself the product of an inter-faith marriage from a time when the “idea of India” was not just an idea but a lived reality, tells the story of her parents: Sumitra, a Kshatriya Hindu from Mysore in Karnataka, and Anees, a Syed Muslim from Deoria in Uttar Pradesh. Woven into their story are recipes from Sumitra’s kitchen, a site of confluence for the diverse culinary traditions she mastered.

The following are excerpts from the book.

Going to Mysore for the first time took some doing for the young couple. There was the guilt of not having told the family there about their nuptials but also, more importantly, the cost of two and a half persons travelling— by the time they gathered the nerve to get there, they had a daughter, who was a little less than three years old.

Anees remembered his brother-in-law, the man who had practically raised Sumitra, vividly. He was among the founders of Kannada cinema, and was making films, including on folklore and Hindu mythology, since the 1940s. He was a freedom fighter and had a breadth of mind that made him a joy to be around. His joie de vivre was the perfect counterfoil to Anees’s quietude, and they got on like a house on fire.

Just when he had learned of Sumitra’s choice, in 1966, he had written Anees a long letter addressing him as ‘Janab’ Anees Chishti saheb, perhaps forgetting for a minute that this was no feudal lord but a twenty-six-year-old struggling journalist who was wooing his thirty-three-year-old sister. But Anees understood that Papanna was trying to make a culturally appropriate point, he understood the spirit of the gesture and was very touched.

Sumitra and Seema were already there in Bangalore when Anees arrived. Sumitra, as part of her duties, was to organize a training programme for the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT) and after they were done with that, they all drove down to Mysore, on a narrow strip of road they were to take many times from then on.

In Mysore, Anees, a teetotaler and generally restrained person, experienced the warmth of large-hearted and flamboyant hospitality, uniquely reflecting Papanna’s world, including his silver screen connections and Mysore, in general.

His nieces, nephews all took to their new uncle with gusto and interest, career advice, a new way of doing this, of somebody who did things differently, whom their beloved and unique aunt was smitten with, and whose presence resulted in giggles and aroused serious interest.

Papanna had a great eye for beautiful shooting locations. Many locales, even today, that Bollywood favours likely bear the imprint of Papanna’s keen exploration. His eye for talent also meant he launched new faces who went on to become big stars, including Saroja Devi whom Papanna had discovered and, struck by how she spoke and looked, asked to audition. He had given the Kannada megastar Rajkumar his first role.

The same talent was extended to taking his young brother-in-law to beautiful spots in Karnataka. Two Ambassador cars full of his entire family accompanied them as they set out, whizzing at top speed till both cars were brought to a halt at Srirangapatnam, around noon, all looking expectantly at Anees to get out. He looked quizzically, only to be told that, ‘It is Friday, it is already near about one o’clock and this is the mosque Tipu Sultan built. Won’t you read the namaz?’ Anees found himself in a situation he had never found himself in—hemmed in by two carloads of Hindus, next to a mosque that Tipu built (opposite a temple), insisting that he say his Friday prayers.

Anees Chishti, a leftist by persuasion and then the founder-editor of the Congress (O) paper Political and Economic Review, was not amongst those who offered Friday prayers. But overwhelmed by the moment and the gesture, he scrambled out towards the mosque. There, a burly bearded man stopped him from entering. Seeing the young women behind him in colourful sarees, bindis, vermillion and mallige hoo (string of jasmine flowers) in their hair as shorthand for a Hindu family out sightseeing, the sidekick of the imam at the mosque thought it fit to bar Anees entry.

Anees eventually had to recite the kalma, like a password and a badge of entry, to persuade the old man to let him enter and read the namaz. The ‘Hindus’ waited patiently outside Tipu’s ruins.

[…]

Whether it was the Emergency or the tremors of the demolition of the Babri Masjid that changed India, Anees and Sumitra realized slowly that the hurdles they thought they had faced when they got together were simply genteel objections compared to what the country was now experiencing.

In all this—Mainstream, terms of trade, fierce and enriching debates and bi-annual trips home, alternating between Deoria and Mysore—it slowly emerged that in the Chishti household, it was the kitchen that had unknowingly become the keeper of the composite secrets and essence of India.

Sumitra, from a radically different culinary tradition, and a ‘working’ woman at that, was deeply interested in matters of the gut and stomach and, along with Anees and his family’s support, ran a most interesting kitchen.

In a small and middle-class space, nothing fancy or particularly Nawabi or Rajwada about it, the two went on to run one of the most delicious and wholesome spaces for a kitchen of India. The approaches to food spoke of the eclectic and easy togetherness that has later been unfairly read down as merely tolerance. It was different and much more than sufferance. Food, like shared lives, made new dishes, aromas and sights possible. In older times, kitchens were segregated spaces. But not Anees and Sumitra’s. Taboos were taboo. It was beyond live and let live. It was a confluence and khichdi—which, it would not be far-fetched to say, was a symbol of a unique civilizational moment in South Asia which made India the exemplar or the exception, an island then amongst the divisive ethnic nationalisms that ensured sharedness did not exist or, where it managed to exist, could not flourish.

My mother went on to compile a recipe book for me, of delectable yet simple recipes of both Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh, both ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’, Kshatriya and Syed, vegetarian and non-vegetarian.

These dishes evoke the taste of a khichdi home that confidently experimented, borrowed, shared and ended up brewing a very special dish. It is called India.

[…]

In the same way that who one marries or talks to or where one lives could be a criminal act (because of new laws on so-called ‘forced conversions’ and restrictions on renting homes to certain communities), food has also become a bitterly contested terrain. What one eats or does not eat is picked at as a differentiator. That is at the heart of new laws around cattle, beef consumption, halal food or mid-day meals too, where politics decides whether eggs will be served to malnourished children.

What this politics of food has tried to erase is a consciousness and knowledge of common roots, exchange of ideas and cross-fertilization that made modern food choices possible. Travellers from distant lands brought new ingredients, seeds, vegetables and fruits. These enabled new ways of eating and cooking, with constant borrowing and lending of dishes, ways of cooking, spices or marinating foods nourishing the process. The samosa may not be as home-grown as we like to believe, or the tandoori chicken for that matter. At the same time, things targeted for being ‘foreign’—like Mughlai cuisine sometimes is—are indigenous, having travelled in another form and then having been perfected in the shape and taste we know today, right here—in India, in Mughal times. Both of these are as Indian as they can be.

Food, if anything, must remind us of how much we reside in the world outside and how much of the world outside resides in us. Deep, inside our gut.