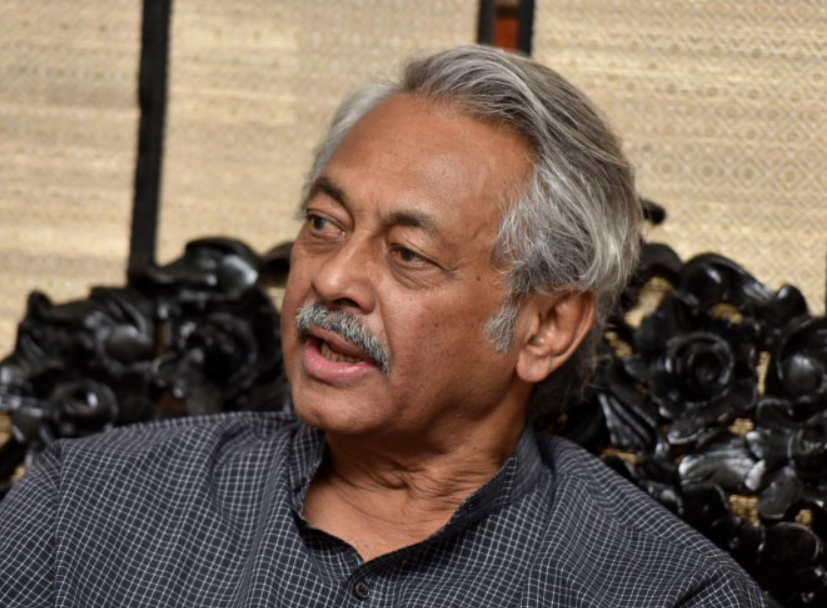

Internationally acclaimed film director Girish Kasaravalli is among the pioneers of parallel cinema in India. The Padma Shree awardee is known for award-winning Kannada films such as Ghatashraddha (The Ritual, 1977), Tabarana Kathe (Tabara’s Tale, 1986), Thaayi Saheba (Mother Saheba, 1997), Dweepa (Island, 2001), Kanasemba Kudureyaneri (Riding the Stallion of a Dream, 2010), among several others. Trained at the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune, his films have been screened at numerous international film festivals.

Arvind Das spoke with him about the recent successes of South Indian cinema, the lack of socio-political critique in cinema, and the ongoing Cannes film festival. According to Kasaravalli, the quality of a film, work of literature or theatre production can be gauged from its ability to transcend time. Edited excerpts:

Arvind Das [AD]: What is your view of recent films from South India, such as RRR, KGF, and Pushpa? They generated much interest and became pan-Indian films. They broke all box office records too.

Girish Kasaravalli [GK]: It is true these films have drawn attention to South Indian cinema and gained audience acceptance. But South Indian cinema drew attention a long time ago. It is not a recent phenomenon. Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s films or Pattabhirama Reddy’s Samskara (Funeral Rites, 1970), BV Karanth’s Chomana Dudi (Choma’s Drum, 1975), and others have received pan-Indian recognition for their cinematic content and aesthetic. Because these films have never been released on a very big scale, they did not get the kind of audience reception [movies get today].

Personally, I am more worried about the content and artistic sensibility these [new] films bring. They get wider audience acceptance and do well at the box office but, well, neither you nor I benefit from it. Whereas if a film is aesthetically well-designed and addresses certain social issues [which have been sidelined], then I think we all get something out of it. I would be happy to see more such films. I must confess I have not seen the movies you mention, which could be my limitation, but I also don’t know what makes these films so engaging.

[AD]: Even popular Bollywood cinema of the seventies and eighties raised socio-political issues, but most films don’t do this now. Would you agree?

[GK]: I have many more films in my mind that address very important social issues in an aesthetic cinematic way.

[AD]: Pattabhirama Reddy’s Samskara, Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Swayamvaram (1972) and Ghatashraddha (1977) won national and international awards and launched a parallel cinema movement in South India. So how do you see the journey of the last fifty years? Do you see new voices emerging on the horizon?

[GK]: Many people are eager to write obituaries for these kinds of films. They say nobody is making this kind of film any longer, but I don’t agree with them at all. Look at films in other Indian languages (I don’t use the term regional language), Malayalam, Marathi, Kannada, Tamil or from the North-Eastern states. We see they are making lots of good films and getting good attention worldwide. The problem is not with the film-maker or the movie but with the infrastructure, which is [only] conducive to screening mainstream cinema in the last 100 years in India. While in Europe and America, there are avenues for small-budget and socially-relevant films, we lack that.

That is why such films are not visible, although very good movies are still being made. The advantage I had when my first film, Ghatashraddha, was released was that the Film Society movement was very strong. They took my film and screened it across India. That is how people from Kerala, Maharashtra and other parts of India came to know about my films.

[AD]: Yes, we lack good film festivals today. I remember seeing your films fifteen years back at the Osian Film Festival in Delhi, which film-makers like Mani Kaul, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, and Gautam Ghosh attended.

[GK]: We need a film society of the kind that screens not mainstream films but those made in other Indian languages. In the seventies, Mumbai had a film society that only screened films in other Indian languages. Today, very interesting films are made not in Hindi but other languages. We need small film festivals with strong content-based films.

[AD]: What role do you see OTT platforms play?

[GK]: When the idea of online platforms came, we thought it would help the small film-makers, but our expectations did not come true. OTT is more concerned about returns, profits, and so on. Kerala recently started a government-owned OTT platform to screen off-beat Malayalam films that have gotten critical acclaim and national and international attention. I thought that was a very good move. In this regard, Kerala has taken the lead, and others should follow. OTT is interested in films made in America—that is the problem.

[AD]: The Cannes Film Festival is on until 29 May. It is celebrating its 75th anniversary. Which national or international film has had an impact on you?

[GK]: I will talk about the last twenty or twenty-five years. Shaji N Karun’s Piravi (The Birth, 1988) has greatly impacted me. Amongst world cinema, I don’t know which one to pick! Roma—I find the film [dir. Alfonso Cuaron] very engaging and interesting. I am not talking about Andrei Tarkovsky, Robert Bresson or Jean-Luc Godard; I am talking about contemporary films. I also found some Russian, Iranian and Latin American films very engaging.

[AD]: You live in Bengaluru. Of late, we have seen majoritarian forces rise in the state, which put a question mark on the idea of India. As we celebrate the 75th year of Independence, there is self-censorship among artists. What do you say about that?

[GK]: We must acknowledge that India is a country of diverse religions, diverse ethnicity, and diverse language, literary and cultural traditions. I would be very happy if everyone respected that. I would not want the North-East to copy Hindi cinema. I would want them to bring their own culture to their cinema. Similarly, I would like Malayalam cinema to return to its social realities, which are close to their heart.

[AD]: Satyajit Ray’s film, Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970), is being screened at Cannes. It raises the issue of unemployment which is still relevant. How do you see him as a film-maker and his impact on Indian cinemas?

[GK]: There is no doubt Satyajit Ray is the greatest film-maker India has produced. I will go one step further and say he is one of the finest film-makers world cinema has produced. Unfortunately, it took three to four decades for Indian audiences to get to know his works. The government and various institutions should have promoted his films across India so that the impact Pather Panchali, the Apu trilogy, and Charulata created would have shifted into the Indian film-making psyche.

Pather Panchali would have created the same sensation [in India] that it created in the world market. Because it was in Bangla, and our distribution networks were not conducive, it was not circulated all over India. They should have done that. If it had, then the complexion of Indian film-making would have been quite different. If the films of Ray, Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen had been circulated well, we could have seen the ‘new wave’ movement much earlier, but people got to know about their films much later.

A very well worked out film or, for that matter, literature or theatre production should pass the test of time. Many of Ray’s films have that kind of power, and though they were made in the fifties, sixties and seventies, they are relevant even today.

I would say Pather Panchali would remain relevant even after a hundred years. It’s not just content but how a film-maker looks at life. I look at how a film-maker compassionately portrays his character. That is what makes it eternal. Ray, Sen, Adoor, and G. Aravindan’s films have that quality.