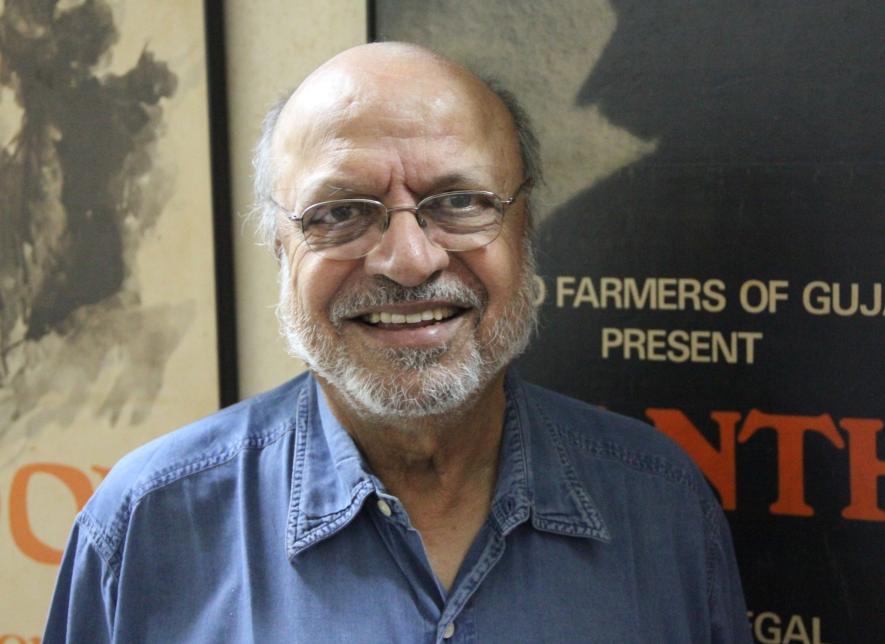

Noted director, screenwriter, documentary filmmaker and Dadasaheb Phalke award-winner Shyam Benegal has been working on a biopic, Mujib: The Making of a Nation, on “Bangabandhu” Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Filmed in India and Bangladesh, it is due to release this year. Last month, Benegal released the poster of his film at the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) in Mumbai. Born in 1934, Benegal is a pioneer of parallel cinema in India and has made numerous masterpieces over his fifty-year career.

Arvind Das spoke to him about his upcoming movie, the role of cinema and filmmakers in India. Edited excerpts:

Arvind Das [AD]: You have made films for fifty years. You are 87, yet you go to the office every day. Why? What keeps you going?

Shyam Benegal [SB]: It is work. Work keeps me going. Currently, I am finishing a big film on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. It is a biographical film that will probably be released in late September.

AD: Earlier, you made movies about Mahatma Gandhi and Subhash Chandra Bose. How is the film on Mujibur Rahman different?

SB: It is a historical biography, very much like ‘The Making of the Mahatma’ or ‘Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero’. It is about an important person from our subcontinent. Sheikh Mujib was a man who created a new nation—Bangladesh. His is a very interesting story, and he was a fascinating person too. He was not from a well-to-do family. He did not have a background like Jawaharlal Nehru’s or Gandhi’s. Nehru was the son of a very famous lawyer; his family was distinguished. Mahatma Gandhi belonged to a family of diwans in Saurashtra. Most political figures have come from such backgrounds, but Sheikh Mujib was from a very simple location. He was a working man, meaning, for instance, if Nehru decided he had no need for work, he already had a particular background, his father’s standing in the society, and lots of money. But Sheikh Mujib came from a middle-class family—not upper-middle-class—he did not have lots of lands or a zamindari.

AD: This film is a collaborative project; could you share some details?

SB: Yes, it is a collaborative effort between the Indian and Bangladesh governments. Recently, we had the 50th birth anniversary of Bangladesh and the 100th birth anniversary of Sheikh Mujib. By the time we started making the film, it was already late, so the film could not be part of those celebrations.

Also Read | “We are all refugees, our homeland is each other”

AD: In the seventies, you made Ankur, Nishant, Manthan, and then came Mammo, Sardari Begum and Zubeida in later decades. You have directed biographical films too. It has been quite a long journey, covering many subjects. What meaning does this range have for you?

SB: Each film is a perpetual learning process. Making a film is like learning more about your own surroundings, your own people, your own country. It is a process of educating yourself while making films.

AD: Many of your films revolved around social issues. Once, you said, cinema cannot change society, but it can certainly be a vehicle for change. Do you still believe that?

SB: Of course, but what films can [also] do is give you insight. You may not have to learn too much! What cinema does is give you an insight, not just about yourself but the environment, your background; it gives insights into your country, your history, and so much more.

AD: You were also a Member of Parliament. We see conflict and violence all around us today. What role do you see cinema play in contemporary society? For example, the recent movie The Kashmir Files has been very polarising…

SB: See that is the problem. Films have a great amount of influence, and they also play a role in shaping your thinking about the world. I have not seen ‘The Kashmir Files’, but I have heard [about it]. While making films, you [a filmmaker] have one responsibility—towards history. The more propaganda your film has, the less valuable it will be. Fact is, you can use films as propaganda, too. But when you are making a feature film dealing with history, you must have a certain amount of objectivity. Without that objectivity, the movie becomes propaganda.

AD: Through “parallel cinema”, you brought many good actors into the Bombay film industry. You discovered Shabana Azmi, and she once said you are a reluctant guru! Why do you think she considered you hesitant?

SB: Shabana was a trained actor. I feel flattered that she thinks I had a role to play, but actually, in reality, she got opportunities because of the kind of roles there were, for which I found her suitable. She made the most of the opportunities and won laurels for her performances in Ankur, Nishant, Mandi, and other films. It was her innate ability. She is very individualistic. Whatever role she played, she made it her own. She owned her roles!

AD: What do you have to say about the current state of cinema?

SB: Cinema has changed a lot. Today, you do not necessarily go to the cinema hall to watch a film, because the whole pattern is different. Due to the proliferation of television, most people watch movies on TV now. And with the OTT platforms, you have an alternate space that has taken over from cinema. You have to make adjustments for different perceptions. So, when you make a film, you wish to see it in a cinema hall on a large screen. But today very few films are seen in cinema halls. You are likely to watch it on television. And that has affected the way filmmakers are likely to make films.

AD: So what do you think is the future of cinema?

SB: Well, we are looking at it [the future]! I don’t know what will be the future of cinema! Cinema has a future but not necessarily as we may have thought it would have. Technology and history both have a role in how cinema gets shaped. The form of cinema itself gets changed. Also, the way you are going to see films—that, too, will impact how we make films in the future.

Read the interview in Hindi here.