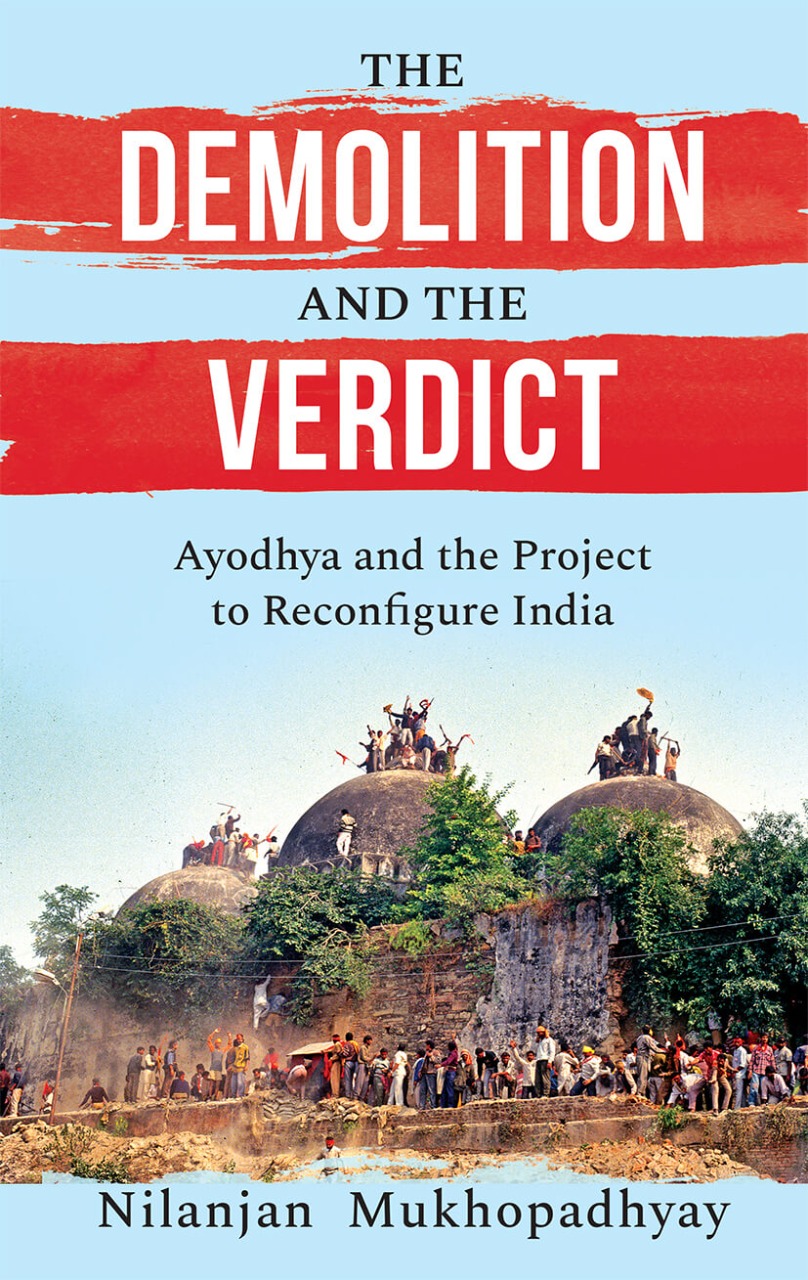

The Ram temple issue has been at the epicentre of Indian politics since the mid-1980s. The question—’mandir or masjid’—dominated political discourse without an apparent resolution—until the Supreme Court delivered its judgement on 9 November 2019. The 5-member bench in a unanimous verdict gave the ownership of the 2.77 acres of disputed land to the Ram Janmabhoomi trust, and ordered it to build a temple on the site. Though an alternative five acres of land was awarded to the UP Sunni Central Waqf Board to build a mosque to replace the demolished masjid, the scales were clearly tilted in favour of the Hindu petitioners, and as many commentators noted, the judges had in effect legitimized what they themselves had called a ‘criminal act’.

This unprecedented, comprehensive book looks at the key moments in the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation, from the events of 1949, Rajiv Gandhi’s ‘unlocking of the gates’ in 1986, L K Advani’s Rath Yatra in 1990, the demolition of the masjid in 1992, culminating in an in-depth analysis of the 9 November judgement. It gives an objective analysis of the core issue: was the mosque actually built by Babur, and did there exist a Ram temple?

Read excerpts from the book.

The Ayodhya movement is unprecedented in the annals of Indian history. The success of the sanghparivar lies in having ensured that the passion and paranoia aroused in the course of the agitation for the Ram temple, was not limited to merely demolishing the Babri Masjid and constructing a new temple in its place. In addition to it, sentiments stirred inthe minds of a large section of Hindus have become integral in their psyche. From a time when the dominant section of Hindus was in principle, of the view that it was obligatory for the majority to safeguard the interests of the minorities, the same people have now begun to think that the obligation is on minorities, to ensure that sentiments of the majority are not hurt. The quote attributed, in a personal conversation, to his mother by a celebrated filmmaker of inter-religious parentage, persistently ricochets deep within the confines of the mind: ‘Yehmulqunkahai’ (this country is theirs).

The consensus on India’s heterogeneity, multiplicity and complexity has been altered in the course of the Ayodhya agitation. The mosque that existed pre-1992 was successfully depicted as the symbol of a past that had to be undone. With this limited objective now fulfilled, there is greater support for seeing the country and its people from a single national-identity majoritarian perspective.

An enhanced agreement now exists for the argument that the majority community, or their representatives, have the primary right to decide what constitutes political and social correctness. It follows from this that minorities, while having the right to ‘live’ in this country, must adhere to terms set by the dominant community. From a time when social integration was encouraged, there is now a push towards compartmentalisation and existence in respective boxes, coming out during work hours for collective activities, but thereafter retreating to our respective ghettos. We can even say that this ‘Gujarat model’ has become pan-Indian. The Ram temple may have been ‘won’, but much remains to be ‘done’—this sense drives a significant section of people.

India was not a land of perpetual hostility, a territory constantly labelling people as ‘them’ and ‘us’. Yet, a primary discordance existed in social discourse on how we defined unitary culture (which is also religion), or as home to a pluralistic society. Differences, divergences, even phases—long and brief—of conflict persisted after Independence.

But, the India in which I became socially and politically aware primarily prided itself on its diversity. For a member of the generation of pre- and early teenagers who witnessed the liberation of Bangladesh and events that followed within India, these developments demonstrated the correctness of choice of the founding fathers for steering the nation on a path paved with the principles of secularism, democracy and egalitarianism. After 1971, banter in school was always marked by a sense of one-upmanship insofar as Pakistan was concerned, not for military reasons alone, but for our social character, because religion was not the primary basis of our social identity. Unlike them, we were a nation for all.

Likewise, we prided ourselves for being part of the same school assembly despite being pro- or anti-Indira Gandhi, during Emergency and in 1977, as even Pakistan and Bangladesh saw democracy crumbling. In the small north Indian campus town where I grew up, the muezzin’s call as well as the temple’s gongs were heard without sounding intrusive to anyone.

[……..]

India changed irrevocably from the early 1990s after this unchannelized throng of voters was mobilized behind the BJP. Most importantly, large segments of societal memory from the pre-demolition era got erased. More than fifty percent of Indians are below thirty and in their living memory, the Babri Masjid structure does not exist—what remains is the temple that is now coming up and the city of Ayodhya being transformed into a must visit, once-ina- lifetime destination for Hindus. Salman Rushdie created the demographic category of midnight’s children. Likewise, ‘high-noon’s children’ exist in India. These are people whose memories took shape only after the sun passed the meridian over Ayodhya’s skies on that cold 6th December Sunday in 1992. That’s when India entered the post-demolition phase of history.

[……..]

Through the Legal Maze

‘Religion is never more tested than when our emotions are

ablaze. At such a time, the timeless grandeur of the Law and

its ethics stand at our mercy.’

—Abdal Hakim Murad

The legal dispute over the plot of land in Ayodhya, less than 1500 square yards in size, continued for 135 years, occasionally at a brisk pace, as during the weeks before the verdict on 9 November 2019 when the bench led by the Chief Justice of India, Ranjan Gogoi, raced against his impending retirement. Yet, and for most parts of these years, the case remained dormant as only the atypical judge was willing to sit in judgement on even peripheral matters related to the dispute. Most members of the judicature perfected the art of, as immortalized in a Bollywood film dialogue, of setting tareeq pe tareeq or date after date.

Judges were reluctant to append their names permanently to the Babri Masjid–Ram Janmabhoomi case because they viewed it as a conflict that required political settlement. Significantly, Swapan Dasgupta, former journalist who was nominated to Rajya Sabha in 2017 before he joined the BJPto contest the West Bengal assembly elections in 2021 (and was renominated to the Upper House after he lost the poll), wrote in the aftermath of the Gujarat riots in 2002 that, it ‘is the myth that a solution is up to the courts’. He contended that the dispute had become a ‘monumental exercise in passing the buck. Parliament is unwilling to take a stand for fear of antagonising the loser. So it takes refuge behind the courts.’ Yet, it was eventually the highest court of the country that awarded the land to Hindu representatives enabling the government to claim that it merely abided by the judicial verdict.

By the time the case was settled and all review petitions rejected in the course of an in-chamber consideration by the newly appointed CJI, Justice S.A. Bobde, and his colleagues on 12 December 2019, no ambiguity remained that this had indeed been one of the rarest of rare civil disputes. It was a sad day when the curtains came down on the case after navigating domains of religion, mythology, history, archaeology, law, governance and politics. It was an ominous day because for the judges ‘possession is indeed nine-tenths of the law’ and that ‘possessory title’ was of greater consequence than ‘property title’. The judges were not guided by the consideration that ‘possession’ of the disputed property was acquired by force and backed by legal sleight of hand on two occasions—in 1949-50 and 1986.

The judges went solely by legal books and not principles of justice. Indeed, the final verdict at the end of decades ofcontestation was a legal tour de force. But only that. Formost luminaries, it was just a case. But was it just that?

At the centre of the clutch of civil suits, clubbed as one, was the legal entity that the Supreme Court of India, like other courts at lower levels of the legal pyramid, termed ‘juristic person’ or a ‘jural deity’, the idol of Hindu deity Ram.

For the apex court to rule in favour of parties representing the idol was more than a tad disheartening. Lead counsel of the Muslim parties, Rajeev Dhawan, remarked dolefully, ‘We won on every point of law. They got the relief.’

The pain in the senior counsel’s words was understandable because the five judges of the apex court awarded the contested land to those individuals and organizations whose action on 6 December 1992 they found illegal and unlawful. They dubbed the Babri Masjid’s demolition as nothing short of an ‘egregious violation of the rule of law’. The judges added that the violence on the medieval structure was executed by activists mobilized explicitly for the act, ‘in breach of the order of status quo and an assurance given to this Court’. The dichotomy between the deductions the judges marshalled from myriad evidence presented before them and the ‘relief and directions’ they pronounced was stark. A full stop on the last legal case surrounding the sixteenth-century structure that no longer exists was put on 30 September 2020 with another ‘winner takes all’ verdict.

It was another sad, but not surprising day. The judge of the special Central Bureau of Investigations court, Justice S.K. Yadav, acquitted all accused of conspiring to demolish the Babri Masjid. The judgement contradicted the Supreme Court decree as well as the findings of the Justice Liberhan Commission. Despite this the special CBI court’s judgement was not challenged in a higher court. In judicial hierarchy, Justice S.K. Yadav, who was appointed to the special CBI court, was much junior but he will remain the unchallenged arbitrator on criminal culpability for the demolition. He based his verdict, the last one of his career, on what was placed before him—evidence as well as questions. Less than seven months after exonerating a galaxy of Sangh Parivar leaders, Yadav was appointed the deputy Lokyukta of Uttar Pradesh by the state government. A decade earlier, after the Allahabad High Court’s judgement in September 2010 ordering division of the disputed property among three parties, it was evident that ‘right questions’ were not framed appropriately even once for any court that had heard the Ayodhya matter. As a result, ‘right answers’ were not given.

The Supreme Court could not but be guided by what it was asked to adjudicate on—appeal(s) against the Allahabad High Court order. It was within its right to examine if the demolition had been a legal process or not. It could argue for providing ‘restitution to the Muslim community for the unlawful destruction of their place of worship’. But it chose to pass a verdict on the limited question of who would leave the court that day with the land in their kitty and secure the right to build ‘their’ place of worship. Likewise, the CBI judge may have been personally aware of the viewpoint of the highest court as well as the Liberhan Commission report. But he refused to examine anything but what was provided by the country’s highest investigate agency, albeit one that had a woeful success rate. Both courts worked within limited legal bandwidth because that is the way law is—providing justice is not the principal concern.

The apex court took ten years to decide on the appeals filed against the Allahabad High Court judgement. This was chiefly due to the unwillingness of Chief Justices to expedite the matter. The case moved to the fast track only after the elevation of Justice Dipak Misra as Chief Justice in August 2017 when he was put ‘under a lot of pressure to decide the case’. He passed on the Ayodhya baton to his successor Justice Ranjan Gogoi whose hastening of the verdict will eternally be juxtaposed with the accusations of sexual harassment against him by a woman staffer of the court, the first time that a CJI faced a sexual harassment charge.

This viewpoint appeared even more credible in March 2020 when Gogoi was nominated to the Rajya Sabha, the first time a government used its power to offer a post-retirement sinecure to a former Chief Justice of India. It was pointed out that Gogoi headed benches in several key cases in which the government had direct interest.

Despite the time it took to arrive at its legal opinion, the apex court judgement provided no balm to those who had been at the receiving end of violence in December 1992. The five judges belied hopes of the finest legal luminaries that after the demolition no court would ‘give any assistance to those who unilaterally by criminal acts destroyed the subject matter of the dispute and violated the Constitution and the law’. Worryingly, legal precedents set in the course of the Ayodhya dispute, especially the criminal matter related to the demolition, are likely to raise its heads repeatedly in future. Even with the Covid-19 pandemic raging through 2020, there were considerable developments over two other shrines, for long on the list of Hindu temples requiring ‘liberation’—the Kashi Vishwanath temple complex in Varanasi and the Krishna Janmabhoomi in Mathura. Civil cases were also filed by parties claiming to represent interests of Hindus over the Teele Waali Masjid in Lucknow and the Qutub Minar in Delhi that was asserted to have been built after destroying several Hindu and Jain temples.