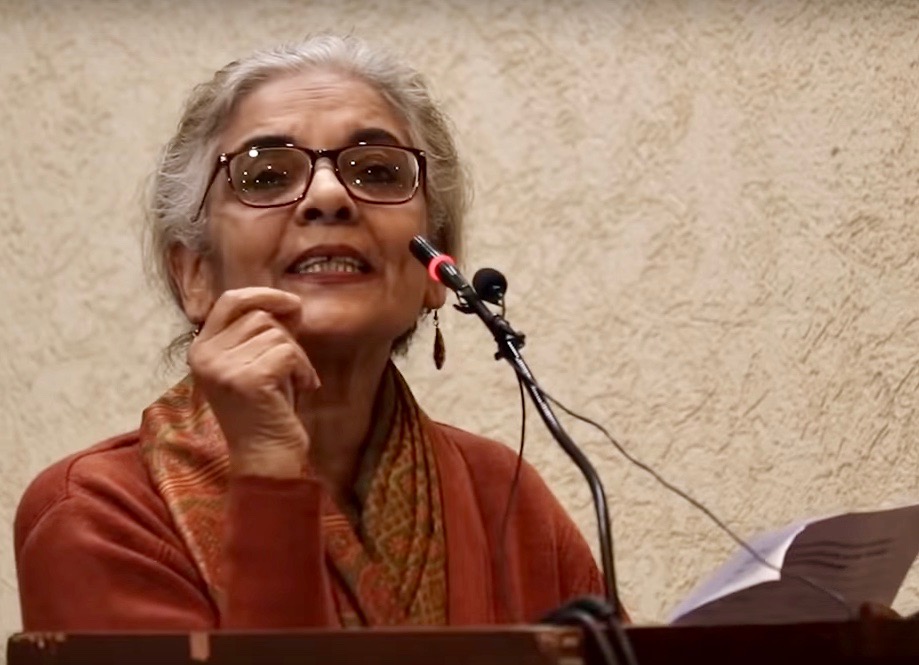

The sizeable pushback from various groups and numerous public protests in the past few years indicate the limits of majority rule and the resistance to redefining our democracy, says the eminent political scientist Zoya Hasan in this conversation with independent researcher, writer and women’s rights activist, Sahba Husain.

Sahba Husain [SH]: This year, the country is celebrating 75 years of India’s Independence. Could you please share with us your thoughts on the significance of these celebrations, given the current political climate in the country?

Zoya Hasan [ZH]: The 75th anniversary of Indian Independence is a landmark in the history of our democracy. Democracy has not only survived, but has thriven and been institutionalized. That’s something to celebrate as India is one of the few countries in the post-colonial world that took up the challenge of building an inclusive democracy in a diverse, multilingual and multi-religious society. India’s stunning diversity has been supported since Independence by a political structure that emphasizes equal rights for all, and protects liberties of religion and speech.

The freedom struggle and the Constitution laid the foundations for the protection of fundamental and civil rights of all Indians. It protects pluralism and equal citizenship more comprehensively than do most countries. But a decent Constitution does not implement itself, and challenges to these core values repeatedly arise not least in the present, when communal movements and sectarian politics have sought to upend its core values.

SH: How would you define India at 75? What, according to you are the landmark moments that have shaped India in its journey since Independence?

ZH: There are many landmark events that have shaped India in the last 75 years. India has built a modern economy, although very unequal, established and remained a functioning democracy which is, however, under stress due to curbs on free speech, lifted millions out of poverty and yet vaster layers of poverty remain untouched, has become a space and nuclear power and developed a policy of non-alignment, which has, however, given way to a burgeoning ideological, military and diplomatic alignment with the United States.

A few of the defining moments in this journey include the first general elections, the Green Revolution, Sino-India war (1962), Bank Nationalization (1969), Liberation of Bangladesh (1971), Pokhran nuclear tests (1974, 1998), the JP Movement (1974), Emergency (1975-77), Mandal Commission (1990), assassination of Indira Gandhi (1984), Shah Bano case (1985), globalization of economy (1991-), assassination of Rajiv Gandhi (1991), Babri Masjid demolition (1992), Mumbai blasts (1993), Kargil war (1999), Gujarat riots (2002), slew of path breaking rights-based legislations starting with the Right to Information Act (2005) and MGNREGA (2005), Mumbai attacks (2008), Lokpal agitation (2011), J&K bifurcation and end of special status of J&K and the Supreme Court verdict in the Ramjamabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute (2019).

SH: What about the constitutional guarantees and the promise of equality for all, irrespective of caste, class, religion and gender? What are the reasons, according to you, for the continuing institutional and social discrimination based on these ‘categories’?

ZH: Equality of opportunity is a value cherished, at least officially, by all modern democracies, including India. The effort to pursue equality in India has been made at two levels. At one level, there was the constitutional effort to change the very structure of social relations. At the second level, there was the effort to bring about economic equality.

A discourse of economic upliftment was part of the process of development and legitimization of the postcolonial state, but we have not been very successful in the promotion of economic equality, which is evident from the failure to remove the division between the privileged and the rest. As aresult, the reach of India’s economic and social development has not extended to those who most need it.

India is falling behind its poorer South Asian neighbours in terms of basic social development indicators. This fact reflects a wider failure to translate faster growth rates into substantial advances in the standard of living for the majority of the country’s population.

India is one of the most unequal countries with dramatically increasing inequality for both income and wealth. India has a serious inequality crisis. The substantial gains that India had made in terms of poverty reduction are under threat of reversal.

The reversal has to be seen in the backdrop of the growth of Hindu nationalism and its inability to conceive of equal citizenship and equal participation as the foundation of democracy. This has been combined with the pursuit of a pro-corporate agenda that involves large scale privatization of a range of public assets from railway stations, ports, airports to stadia and roads. Besides, the substantial middle class shares the same ideological conviction regarding the benefits of private enterprise.

Also read | “The Struggle for Larger Azadi has Never Been More Urgent than it is Today”

Redistribution is an important function of government – a strategy which can combat rising inequalities, but the opposite is happening, in fact, mass poverty, inequality and unemployment have increased significantly as many governments resist or even prevent redistribution. There is no acknowledgement of the increase in inequalities. Not surprisingly, the ideologues of Hindu nationalism never ever refer to distributive justice or equality.

Taking a long term view, this is not just an economic failure of just this government, it is a wider democratic failure. Popular discontent is directed primarily against under-representation in public institutions and hence the focus is on power sharing and empowerment, and not against inequalities, disparities and injustice per se. Social justice demands are seldom located in the realities of political economy and redistributive challenges emerging from it.

SH: Your work has focused on state, political parties, ethnicity, gender and minorities in India. You also served as a member of the National Commission for Minorities in 2006-2009. Has the status of minorities and women in India improved in any significant manner in the decades since independence? What are the main challenges confronting them today?

ZH: It is no secret that Muslims are the most under-represented group in public institutions in India. The Sachar Committee Report documented the dismal socio-economic status of Muslims. That Report demonstrated that on most socio-economic indicators, they were standing on the margins of structures of political, economic and social relevance and their average condition was comparable to or even worse than the country’s acknowledged historically most backward communities, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Muslims exist almost entirely outside India’s mainstream economy (both the organized private and public sector). Fewer than 8 percent of urban Muslims formed part of the formal sector while the national average was 21 percent.

Fifteen years later, with most of the Sachar Committee’s recommendations quietly shelved, those numbers are unlikely to have improved. Indeed, some gaps have widened since 2014. This phenomenon has extended to elected assemblies. The Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) rarely gives a party ticket to Muslims. It has shown that electoral majorities can be won without their support.

As for Muslim women, the vast majority of them are poor which reflects a lack of social opportunity exacerbated by their marginal status in Indian society. They are conspicuous by their absence in the world of politics, in the professions, bureaucracy, universities, and public and private sectors. They rarely figure in the debates on empowerment, poverty, education or health, nor does their vulnerability arouse much concern, except with regard to personal laws or the hijab controversy now.

Muslim women lack political representation and have no voice in governance and public institutions. With so few Muslim women present in decision-making bodies, their specific concerns can easily be overlooked in the unfolding story of Indian Muslims and their marginalisation under a majoritarian regime.

SH: As a political scientist, you have done extensive research on social and educational aspects of Indian Muslims and Muslim women. Given the consolidation of the RSS/BJP in the country, what are the specific implications/consequences today for Indian Muslims, their access to education, health and livelihood?

ZH: There is cumulative evidence that discrimination against Muslims in employment, education and housing has increased. Arguably, their exclusion is related to the expansion of majoritarian nationalism. This is not a new phenomenon but this has been on the rise in the past few years.

However, state policy does not recognize the institutional exclusion of minorities and inter-group inequalities. Citizenship Amendment Act( 2019), which allows non-Muslims from three neighboring countries to fast track their citizenship by creating an exemption from the ‘illegal migrants’ category on the basis of religion, is the most striking push against inter-group equality.

At the same time, minorities lack the capacity to challenge their exclusion and systemic discrimination because they lack the power and access to decision-making required to challenge their disadvantaged status.

SH: You had written, in the context of post-Ayodhya that ‘majoritarian notions of democracy have acquired new acceptability in recent years and notions of majority rule have been pushed to achieve a restructuring of the Indian polity.’ Could you please elaborate on this, given today’s political reality?

ZH: The general elections of 2014 and 2019 represents a tectonic change in Indian politics as it signals a shift in the political landscape to the right. For the first time, the electoral majority rests with the party that overtly represents Hindu nationalism, which claims distinction from received Indian nationalism. The right challenges secularism with its emphasis on democracy, religious neutrality (or equal standing for all citizens, regardless of religion) and social justice but it also seeks a communal reconstruction of national identity and derides the principle of minority rights as an unwarranted privilege.

This is beginning to change the meaning of democracy in the direction of majority rule – a system of political rule by a political/ethno/religious group elected under a system of universal suffrage. This means giving primacy to the majority community in the public sphere based on the claim that a nation’s political destiny should be determined by its ethnic majority. Majoritarian politics seeks to reconfigure the Indian nation as one that belongs exclusively to the Hindu majority.

The Ayodhya and Kashmir events indicate strong attempts to operationalise the majoritarian version of nationalism. Courts, legislatures, and political parties have facilitated these moves to take place within the constitutional-democratic framework.

Furthermore, what differentiates this regime is the space it provides for the construction of an enemy within, which it needs in order for majoritarianism to thrive. This has served to polarize the electorate by creating a permissive climate which enabled a politics of division and fear to hold sway. This is done by promoting a sense of vulnerability and victimhood in the majority community in relation to the so-called threatening Others, namely Muslims.

Equally significant is the push towards the establishment of an authoritarian regime. The combination of majoritarianism and authoritarianism, especially after the 2019 general elections has resulted in democracy becoming thinner, not accidentally, but deliberately. These two processes have reinforced each other giving rise to disquiet about its impact on India’s democracy.

SH: Words such as citizenship, democracy, nationalism, secularism, freedom and justice seem to have acquired new meanings and significance in recent years. So have dissent and resistance. What are your thoughts on it and on the changing character of the Indian State? What does the rampant use of draconian laws and heightened surveillance against ordinary citizens mean for democracy in present day India?

ZH: India’s democracy has worked well precisely because no single culture or language or identity is central to its identity or unity. When nationalism is defined by a single identity, which can either be language or religion or ethnicity, then, nationalism gets derailed into majoritarianism. This thought defines ethnic or religious majorities as a nation’s rightful owners. This is not nationalism which reflects the collective self. The collective means that everyone who constitutes the nation should be included as equal citizens. Thanks to the legacy of the freedom struggle this inclusive nationalism came to define India’s post-1947 national identity.

The current notion of nationalism stands in stark contrast to the path chosen by modern India which started its journey on the basis of a broader concept of inclusive nationalism, and indeed much of India’s social progress was closely tied to its preservation of diversity and cultural heterogeneity. Besides inclusive nationalism does not place the nation above the people; national development consisted of the promotion of the welfare of all the people.

As we approach the 75th anniversary of Independence, one finds a growing tendency on the part of the state to control all facets of life—politics or social equations or culture or culinary habits. It’s no secret that the BJP-led government doesn’t take kindly to criticism, in fact, it sees dissent as sedition. Any protest or questioning by citizens is often viewed as a threat to the nation and hence discouraged, in fact, it is penalised.

The larger intent is to create a state where there is no opposition, either at the electoral or at the ideological level in terms of expression of alternative view. The arrests and filing of criminal cases against several public intellectuals, human rights activists, journalists, and also other creative persons including comedians and cartoonists indicates an increasingly restrictive environment for dissent and opposition in India. These measures include press censorship, Internet shutdowns and crackdowns against non-violent protestors.

The full force and authoritarian tactics of the government was showcased in the government response to the two largest protests in our post-Independence history – the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests and the farmer’s movement. The attempts to change the storyline of peaceful protests into one of “violent, anti-national, separatist” movement in case of both the abovementioned protests follows a certain pattern of criminalizing protests. How else does one explain the police overkill over a tool kit for farmers’ protests?

Despite these transgressions, I don’t share a sense of gloom about the future of India’s democracy even though democracy requires a level playing field which currently we don’t have. There is a sizeable pushback from various groups and the numerous public protests we have witnessed in the last few years indicates the limits of majoritarian rule and the resistance to redefining of our democracy to make it majoritarian. India’s incredible diversity and regional assertions have also created major hurdles in the path of the communal-authoritarian regime.

We are, moreover, talking about a democracy that has lived and worked for more than seven decades. Indians value the long democratic experience and the diversity, argumentation and the plurality of opinions that are a part of this experience. That’s India’s distinctiveness. It will survive the present attempts to stifle it.

SH: Your active commitment and participation in the women’s movement in the country, particularly during the Shah Bano agitation and against the Muslim Women’s Protection Bill in the 80s is well known. More recently, there were countrywide protests by large numbers of women against the CAA. Please share with us your experience and understanding of these struggles over the years and lessons learnt/to be learnt.

ZH: Muslim women’s participation was the most striking feature of the public protests against the CAA. They were the life and soul of resistance against this discriminatory law which for the first time introduced a religious test for citizenship. These protests demonstrated a new vocabulary and grammar of politics as a form of civil disobedience. By using the Constitution and national symbols, Muslim women challenged the discourse of majoritarianism and anti-nationalism on a widespread scale, cutting across a range of demographics and geographies.

These protests are significant because they saw a huge participation of women on non-gender issues and in complete defiance of state and police violence. It is indeed striking that women were out on the streets for a cause that was not women-specific, not about sexual harassment or domestic violence. What is also remarkable about Muslim participation in these protests is the assertion of an Indian rather than Muslim identity. What is even more remarkable is that Muslim women redefined the boundaries of politics set by community leaders and clerics and focused on issues that matter to people notably equal rights and equal citizenship.

Read the conversation in Hindi here.