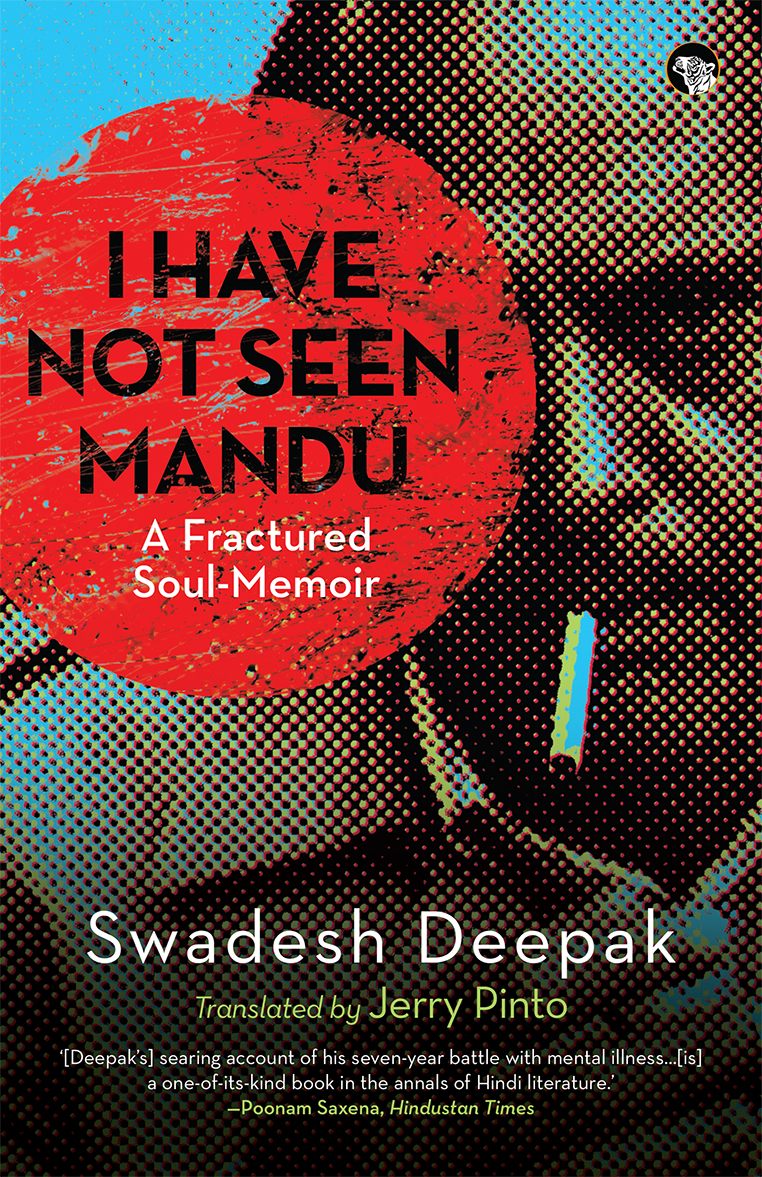

When Swadesh Deepak — celebrated Hindi playwright and short-story writer — arrives at PGI, Chandigarh, after having tried to set himself on fire, the doctors don’t know if he belongs in the burns unit or in the psychiatric ward. He’s living a ‘curse’. A dangerous seductress, his Mayavini, is taking revenge for his insulting rebuff at her wish to visit with him the famous lovers’ palace in Mandu. She comes to him at night, sometimes with three white leopards, and she leaves the smell of her body in his nostrils. When he tries to kill himself, she tells him he will not die. He is firmly in her clutches, but he will tolerate anything for her, from humiliation at the hands of acquaintances to carnivorous worms under his skin.

This fractured, shattering narrative among the most unusual books ever published in India records Deepak’s descent into madness and his brief, uncertain recovery. Shortly after it was published, he left home for a walk one morning and never returned. As the translator, Jerry Pinto, writes in his introduction: ‘[Deepak’s] words carry all the scars of who he was and what his illness had made of him. His voice echoes from the bottom of a well.’

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Chal Khusrau Ghar Aapne*

A leaf flutters and a new eye opens

The sky fills with the flight of new birds

New fish are born in the rivers

And green spreads as far as the eye can see

In the dust, the fresh footprints of children.

—Rajesh Joshi

Their real colour was white. It was now the yellow of marble. They were thin at the top and at the bottom. Swollen in-between. That paunch upset their symmetrical lines. Once they fall over, they can’t right themselves.

The burnt flesh of my arm has liquefied. Maggots fall from the skin onto my bed. Chacha Harnam Singh’s favourite word is ‘tezi’ (energy). When I said that my arm had been abnormally burning through the night, he would say that the medicines were infusing it with a new tezi.

All night, my arm jerks and throbs. The ‘energy’ in it keeps increasing. The burning increases, burns brighter, deeper.

Swadesh Deepak, externally hateful and dirty. Inside, a river of filth. Anyone might be revolted even to encounter him in a dream. Mayavini too is terrified. She has not come. The hostel for dream beings is empty. It is filled now with swollen worms who loiter there. Before it is morning Mr Shimla goes into the verandah to smoke a beedi. Seeing me moving constantly on the bed, he stops. He sees the worms crawling on my neck. He sees the worms slithering and slipping over the white bandage on my arm. He sees the worms, swollen in the middle. He screams in Hindi. ‘Behencho… The professor’s crawling with worms.’

Even after his long shriek, she does not come. Sikandar drags him outside. The awakened patients sit in their beds like statues, looking in my direction. They cannot get up the courage to scream.

Sikandar uses his slipper to kill the worms coiling on the bed. Harnam Chacha gets me off the bed and onto the stool.

I feel no fear. By evening, millions of worms will be at work inside me. And then the last word of the play can be written: Curtain.

I am afraid of living, not of dying. I explained it myself: what else would a bastard like you get if not worms? How much pain you have inflicted. Nimmi, her face blanched, had said: This is no curse of mine. However cruel you were, you were as tender.

Soundlessly, I screamed—Take my memory away, please. Please kill my memory.

Message after message on the pager. Dr Vasantha on night duty. She gave me a glass of water to drink. She put a hand on my head. She asked: Are you in pain?

—I never feel any pain. I am a cold horseman.

—Deepak Sir, aap kitna abhaaga hoti, dard nahin hoti.

(You are so unfortunate; don’t you feel pain?)

—Please Vasantha. Don’t speak Hindi badly.

She took off her glasses and wiped her eyes. She put on hers again.

She knew that when I speak English continuously, I have retreated to my secure country. No sorrow there, no joy. A limbo of the half-dead.

—Vasantha, Vasantha, please don’t cry. I will never abuse you.

—Main dar se nahin rota. Pita ki yaad aata. (I do not cry out of fear. I am reminded of my father.) Tough, cruel like yourself, never crying. He didn’t cry the day he was hanged. Sedition. Anti-national activity. I have terror dreams.

I no longer minded her bad language.

—Agar Andhra nahin to Bihar ki jungalon mein maar di jaaoongi toh last moments mein aapko yaad karta. (When I am killed in the jungles of Andhra or Bihar, in my last moments, I will remember you.)

—Vasantha. My child. My daughter. You have no right to die. You have to give birth to a hundred warriors.

At that time I did not know that Vasantha was Apoorva from Sabse Udaas Kavita. I was pregnant with her.

Looking carefully at the ceiling, the nurse tells Vasantha that Dr Naidu is on leave. Dr Shrikant is on his way from the Burns Unit. And I am to be shifted to the Burns Unit on Dr Chari’s orders.

Harnam took off my choga[1] and dusted me down with powder. He put a new one on me. He did not know that neither the reek nor the worms would die with powder. Some stinks become a part of the soul.

As Swadesh Deepak’s body now reeks of worms.

BURNS UNIT

Dr Shrikant is tall and his arms are proportionately long. His thin long fingers show he is an artist in the cutting of burnt skin. I did not verify this because I was sure he was Saratchandra’s Srikanta.[2] He was not our kind of dwarf poet-leader. From my arm, the maggots fell, plop, plop, plop. There was a black cloth on the table. They wriggled madly on the black cloth on which they showed up clearly.

Tiny demons dancing.

Ma, illiterate, would invent new words. Yes, I remember.

‘Kulbul-kulbul’ go the worms.[3] Shrikant asks Vasantha, ‘What is wrong with him, Dr Vasantha?’ Vasantha tells him that everything is wrong with Swadesh, Dr Shrikant.

Dr Shrikant has shared in the sorrows of many. He has understood everything. Now he will not ask anything about me. He looked at the mini-demons on the black sheet. He opened a bottle and sprinkled some powerful medicine over the worms. The swollen slugs died on the spot.

The nurse proffered a tray of instruments. The worms had turned her stomach. Her hand trembled.

Shrikant took the tray from her. He ordered—Go and call Sister Randhawa here immediately. Only she can assist on such a case.

Vasantha asked if there would be much pain.

—Not in the beginning. The skin is dead. But when I go deeper, it will be very painful. You can sit outside. I don’t need you.

—I will stay. My father may need me. I need to get familiar with pain.

Shrikant fell silent. He was deeply sad. He understood that Dr Vasantha would not live long. In the flower of her youth, the police would murder her. And call it an encounter.

Sister Randhawa came. She would retire next year. Her self-confidence shows in her face. She knows me. She teases:

—Deepak, you’re always up to something. Other people breed poultry. You breed worms. Whatever you touch makes a loss.

The scissors came forth. Shrikant cut the knot. He took hold of a loose end.

—Swadesh ji, close your eyes now. You will ask nothing. I’m going to take off your bandage without wetting it.

It will strip the skin off too but that will reveal the area where these worms have their nest. We call it ‘Operation Search and Destroy’.

Dr Shrikant took hold of the bandage and yanked. I jerked an inch or two in the air. Sister Randhawa anticipated this reaction. She held my shoulders down.

Pain, waves of pain. Waves that flooded in and ebbed only to return.

Vasantha—Papa, you may talk to yourself. You are an actor of the silent era.

A strong medicine was sprayed over my arm. The stink became a reek and turned into a part of my body.

My lame memories beleaguer my crippled world. Was anything left unbroken?

Why are the heavenly forces my enemies? Pain of the kind to shake my dreams.

That night when I slit both wrists with a blade, I placed my hands in a tin. I did not let a single drop stain the sheet or the floor. I’ve always liked cleanliness. Parul goes to fetch a doctor.

Geeta keeps slapping me, a series of light slaps. She lights a cigarette and stuffs it into my mouth. I smoke it. She teaches science. Later she said that in such cases one does not allow the patient to fall asleep or else…

In my heart of hearts, I abused her viciously for that ‘or else’. She could have let me go, she could have let me become an ‘or else’. Dying is the most important task for me.

I tried three times and three times I failed. I lost my reputation.

My Bronze Age did not end. I should abandon myself. Why does one always think of someone else’s body while having sex?

In those days, I found thermometers very sexy. The movements begin.

Oh Krishna! You have said: Of the rivers, I am the Ganga. Why do you not give me my share of Gangajal? You have said: Of the seasons, I am the spring. Give me back my handful of spring, Krishna. Does Yamraj, the Comptroller and Lord of Death, no longer heed you? Krishna, you could throw Parthasarthi into the fire of war. Why did you stop me from burning myself to death?

In his last years, my father changed totally. Khadi clothes, for instance. He was, of course, a scholar of Urdu. But now he learned to write Hindi. Urdu translations of my stories began to appear in the government’s Urdu papers. They would not publish the translator’s name. I would get money orders for a hundred rupees at the Rajpura address which I would gladly accept. This was the reason why, until his death, I was thought of as an Urdu writer. The Hindiwalas would not accept me because I would not allow myself to take the protection of a school or an -ism by aligning myself with it. My father complained: Yaar, don’t write such dark stories. When I translate them into Urdu, it hurts me.

He was smart. He was off before my years of darkness began.

My mother’s around. No one had told her. She’s almost deaf. Speaks in a shout. The old lady is a broken drum now. But her style is unchanged. If she finds out, she’ll come to PGI. And then! First, she’ll describe in gross detail the private parts of the doctor’s mothers and sisters. Then she’ll garland them with other abuse.

Next: a royal command—Take Kaka home. I will have prayers said for him. This is obviously some woman’s doing.

The day before she died, I sat with her for hours. In her last hours, she mistook me for her brother Inder. She kept talking to me, calling me Inder. She was happy that Inder had come to visit. I was pleased that she died happy.

Notes:

1. A loose shirt.

2. Saratchandra’s Srikanta (1917) was a love story between Srikanta and Pyaari, a child widow forced into dancing.

3. ‘Chulbul-chulbul karti aayi chidiya’ (The birds chirp and chitter; chulbul-chulbul being onomatopoeic) is the usual song. It is unlikely that his mother, however illiterate, would have mistaken chidiya (birds) for keede (worms), so this conflation is probably Deepak’s way of dealing with his body’s betrayals. Or creating an alliteration.